By Kayleigh Faur

The ocean is a big part of our planet, so much of it is unexplored. There seems to be more knowledge about space than what’s hidden in the depths of the sea. Gradually we have been able to explore deeper into the ocean and seeing species being discovered that look more like the fictional creatures we’ve created hidden in space. Within discovering there is also rediscovering species, ones that have been thought to be extinct for around 80 million years, with records dating back over ‘360 million years, with a peak in abundance about 240 million years ago.’ (McGrouther) The Coelacanth had made a return, adding another fossil to the rediscovered collection.

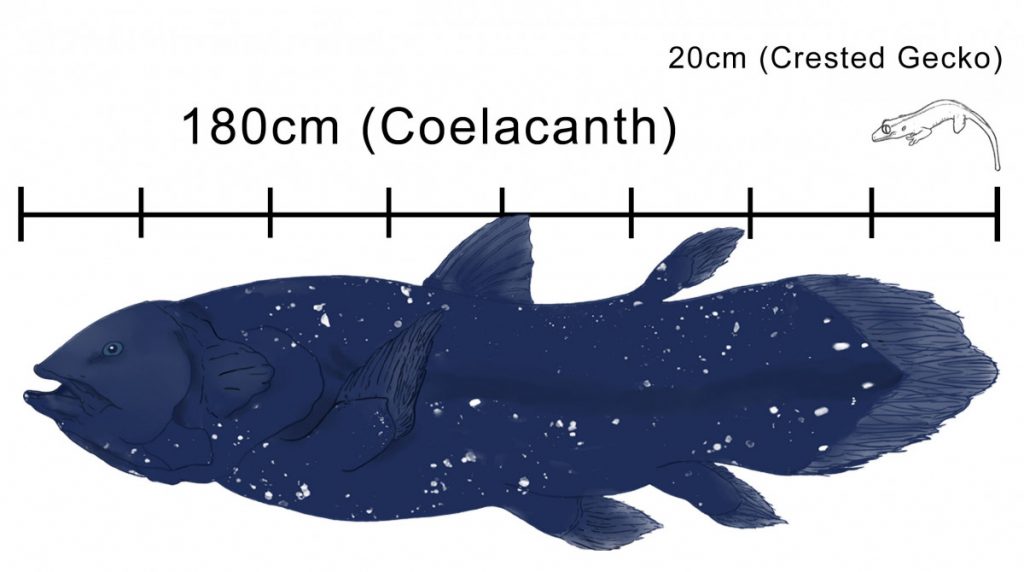

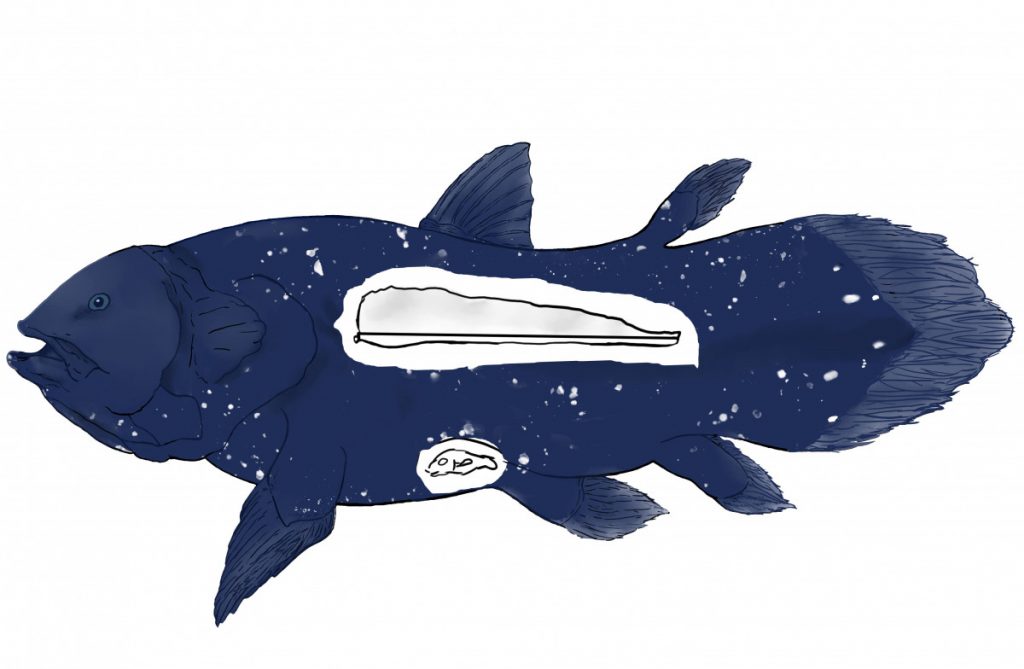

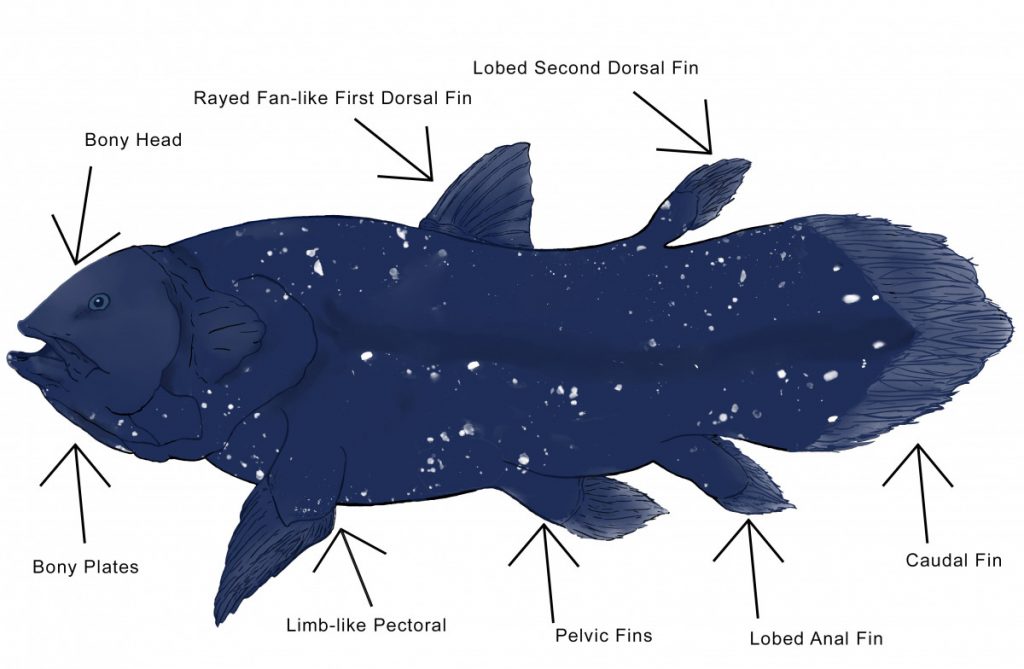

The Coelacanth’s length has been recorded to reach 180cm, with a weight of about 209 pounds. Focusing on their spines and rays the Meristic Count records that the; “First Dorsal Fin: Eight Spines, Second Dorsal Fin: 30 Rays, Anal Fin: 27-31 Rays, Pectoral Fin: 29-32 Rays, Pelvic Fins: 29-33 Rays, and Caudal Fin: 25+38+21 Rays.” (McGrouther) There are other notable key features of the Coelacanth, such as their shark-like intestines with a spiral valve, and their axial skeleton composed only of “a hollow tube of cartilage called a notochord.” (MarineBio) In their skulls, there are hinges, allowing them to consume larger prey, and their swim bladder is filled with fat, this helps provide buoyancy. The Coelacanth is ovoviviparous, meaning that they bear live young.

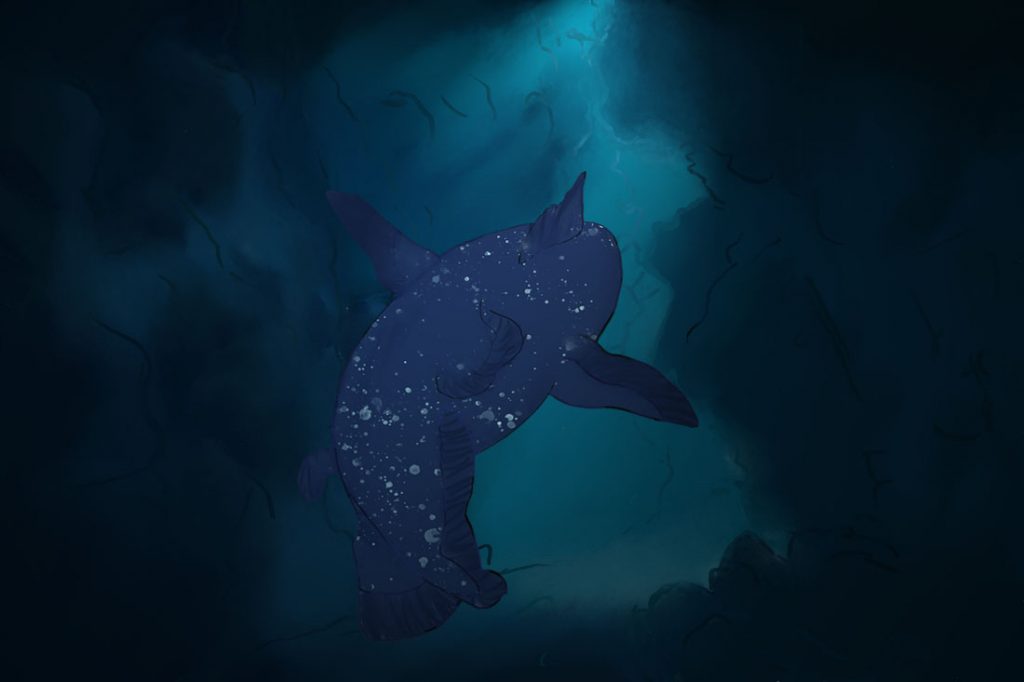

Two types of Coelacanths being discussed both have a lifespan lasting around 80 to 100 years. Usually found in depths between 90-200m, but also been recorded in depths around 700m. The Latimeria chalumnae was found in the West Indian Ocean, which tends to be a darker blue color, highlighted with distinctive white flecks, that researchers have used to distinguish different individuals. The coloration actually gives chalumnae an advantage for camouflaging against rocks that are covered with white sponges and oyster shells. For the Latimeria menadoenis, it’s commonly found in the Indonesian area, with a coloration tending to be more brownish-gray than blue. The coloration seems to be the biggest difference between the two, even the time of day they leave their caves are similar. Scientists had tagged the species with sonic devices, discovering that they leave the caves at “the same time late each afternoon to forage along the coastal during the night.” (Marine Bio) It’s also important to note that the reason they wait for it to get darker, is because the light is too harsh for their eyes.

Blending against the rocks, huddled in the caves as we wait for the bright light that illuminates the world outside our protected area. When the light becomes dimmer, we are able to begin the day, the light is too harsh for eyes, we have an adaption for the darker parts of the day. It seems to be a layer in our eyes that can cause a reflection, its how I’ve been able to spot others in our groups. There is a few hundred that is in our groups, it leaves ample opportunity to choose a mate, but there has been this one male that seems to be catching the entire clutch’s attention. We mate one at a time, but there is little faith in returning to that same mate.

Bibliography

“Coelacanths ~ MarineBio Conservation Society.” MarineBio Conservation Society, 7 Mar. 2020, marinebio.org/species/coelacanths/latimeria-chalumnae/.

“Coelacanth.” Sea and Sky, www.seasky.org/deep-sea/coelacanth.html#:~:text=They%20can%20weigh%20as%20much,cats%2C%20dogs%2C%20and%20dolphins.

Coghlan, Andy. “Zoologger: The Fossil Fish That’s a Serial Monogamist.” New Scientist, 20 Sept. 2013, www.newscientist.com/article/dn24240-zoologger-the-fossil-fish-thats- aserial-monogamist/?ignored=irrelevant#.VHZe84uUd8E.

“Internal and External Anatomy of a Coelacanth.” Internal & External, faculty.montgomerycollege.edu/gyouth/FP_examples/student_examples.20191023.1305.tls/rosanna_deshetler/internal_external.html.

McGrouther, Mark. “Coelacanth, Latimeria Chalumnae Smith, 1939.” The Australian Museum, New South Wales Government, 2 July 2019, australianmuseum.net.au/learn/animals/fishes/coelacanth-latimeria-chalumnaesmith1939/.

Thomson, Keith Stewart. Living Fossil: The Story of the Coelacanth. Hutchinson Radius, 1991.

Vosjoli, Philippe De, and Allen Repashy. “Crested Gecko Care Sheet.” Reptiles Magazine, www.reptilesmagazine.com/Care-Sheets/Lizards/Crested-Gecko/.

© 2020 Kayleigh Faur