Bruce Nauman, by his own admission, is a man who spends long periods—even years—not working, just trying to decide what to make and what to say in his art.

A dry period in the 1970s made him doubt his entire future as an artist, as he told Ronnie Cutron in Interview Magazine, “I wasn’t doing anything and I was worried. I thought I might have to give up art, but I couldn’t think of anything else to do.”

But despite, or perhaps even party because of this silence, other artists are pretty constantly on the lookout for what Nauman says or does.

Subscribe to Observer’s Arts Newsletter

The Nauman watch has been going on for almost 40 years. If Nauman’s admirers and detractors agree on one thing, it is his influence. For better or worse, Nauman has shaped the art of his generation, say critics who admire him (Peter Schjeldahl) and those who don’t (the late Robert Hughes). That’s quite a feat for an artist who eschews anything like a signature style.

Nauman is also a man who rejects the idea of having an effect on others. “I don’t like to think about being an influence. It’s embarrassing,” the laconic artist is oft quoted as having said.

As embarrassing as that might be for the notoriously shy Nauman—he rarely makes appearances—it’s undeniable. So is Nauman’s now-venerable status, with the retrospective “Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts” at the Museum of Modern Art and at MoMA PS 1 that runs through February 25. Nauman the rebel, at 76, is now a classic.

His Starting Point: Making Fun of Everything (Including Art)

In Nauman’s early work (after he put drawing and painting aside) he took black and white photographs of himself pacing through an interior space. His medium was photography, but also his own body, which kept his costs low. For Minimalist art, the (lack of) budget was the aesthetic, which became a manual for dirt-poor younger artists. The much-reproduced photograph, Self-portrait as a Fountain, 1966, which shows him spitting an arc of

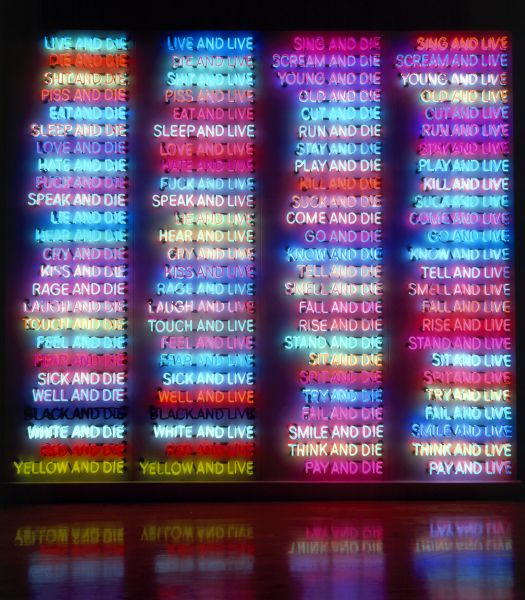

Soon no-budget satire with his body wasn’t transgressive enough for Nauman, even though he made a nine-minute video in tactile black-and-white close-up in which he lifted his scrotum up and down, called Bouncing Balls in 1969. It’s on view at PS 1. Neon would become the medium in which Nauman depicted flashing stick figures committing taboo acts, while statements blinked on and off that lurched between slapstick and self-importance. One neon work simply flashes WAR – RAW. Another alternates between EAT and DEATH. Another is a grid of a few dozen sayings—for the indecisive?

Not to impose too direct an influence, Jenny Holzer’s electric messages and tombstone inscriptions seem to be taking cues from Nauman. Holzer counts herself among his admirers. That long list includes Kiki Smith, Tony Oursler and Mike Kelley.

“There are certain artists that come along and they give subsequent artists permission, [so] you can do anything you want,” said Peter Plagens in a video made for Nauman’s exhibition at Tate Modern in London in last year. Plagens, a painter as well as a writer, is among the many art critics in Nauman’s camp.

He Couldn’t Stick to Anything

“Disappearing Acts” is an apt title for an exhibition devoted to an artist who weaponizes a medium and then abandons it. “I’ve always had overlapping ways of going about my work. I’ve never been able to stick to one thing,” Nauman said in an interview published in 1988.

Nauman eventually put neon aside after high-jacking it for messages of doom and juvenile jokes, often involving figures with dueling erections. The late critic Robert Hughes, not a fan, called the work “psychic primitivism,” and called Nauman “the artist as nuisance.” Nauman (and his artist fans) probably would not have objected to either label.

But there were things that he did oppose. One was political art, that is, until he found a political issue that moved him. His 1981 construction South American Triangle was inspired by the 1981 memoir Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, by the persecuted Argentinian publisher Jacobo Timmerman. Nauman suspended three eye-beams in the air. A chair is suspended from one of them, low enough to hit someone in the face. (A similarly constructed composition of eye-beams and chairs, White Anger, Red Danger, Yellow Peril, Black Death, 1984, is in the current MoMA show.) The ensemble conjures up the isolation and vulnerability of a victim of torture. The work is also an uncanny prefiguration of Ai Weiwei’s later ensembles of suspended chairs. Ai Weiwei knows persecution. It turns out that he may also know Nauman’s work, although a representative whom I contacted couldn’t confirm that.

You Can See the Trickle Down of His Work in Any Contemporary Art Institution

Nauman’s most brazen constructions scared away direct imitators, but his need to offend or wake up the audience had an emboldening effect on artists from Paul McCarthy to Diana Thater. In the 1987 video, Clown Torture, a can-you-top-this spectacle, a clown in full make-up rages while he sits on a toilet. Carousel, 1988, is a merry-go-round of dead animal forms dragged in a circle. Sound, Nauman learned, was a way to keep from being ignored, an inescapable oppressive annoyance, whether as a clown (at PS 1) or as a hall of disembodied voices (on MoMA’s sixth floor). Think of it as a soundtrack for his mute 1973 lithograph that reads, “Pay Attention Motherfuckers.”

The video work Mapping the Studio (Fat Chance) John Cage, 2001, is an extended visit to Nauman’s squalid studio at a time when he was at a total loss for ideas. It observes the comings and goings of mice and a cat, but the artist is never in sight. Letting the camera roll and observing that studio for hours on multiple screens is wryly entertaining. Yet Nauman’s artist’s block and his comic mini-epic reflection on it draw us in because Nauman, to put it mildly, is more than a failed artist. I can’t think of another artist who could have gotten away with exposing his own weaknesses, or who would have bothered trying.

Perhaps this is why, even in the early days, in the 1960s, Nauman’s most loyal fans were other artists, mostly his peers in L.A., where he settled after art school.

And clearly there are some things that Nauman regards at least semi-seriously. “I think that recognition by your peers is really more important than anything else. It was to me at that time and still is,” Nauman said in an interview for the Archives of American Art in 1980.

Recognition understates the matter. Whether it’s in self-portraiture, Minimalism, Conceptualism, video, neon aphorisms, installation art or sheer disgusting outrage, Nauman has pointed the way and others have taken the cue. In 2008, the New York gallery then called Zwirner & Wirth even organized an exhibition that paid homage or borrowed from him. The artists in “Yes Bruce Nauman” included Charles Ray, Glen Ligon and Rirkrit Tiravanija. There was also Mungo Thomson, who made a bumper sticker out of Nauman’s 1967 spiral neon statement The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths. Better that as a bumper sticker than “Pay Attention Motherfuckers.”

And online, you can find Francesco Vezzoli’s 2014 tribute to Nauman, The Return of Bruce Nauman’s ‘Bouncing Balls.’ Vezzoli hired the gay porn star Brad Rock and put him with his back to the camera against a backdrop of mountains with a blue sky and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 playing, swinging his private parts like a flag in the alpine air.

It’s just another place Nauman’s influence can be (all too?) clearly seen.