My last name is Paisley. I know - kind of hilarious for a textile designer. Apparently this sort of seeming coincidence is referred to as Nominitive Determinism, and there are countless examples. One of my favourite examples is Dr Dick Chopp, the Texan urologist who is known for performing vasectomies. Anyway, I’ve always felt quite connected to the swirly world of the paisley pattern, from psychedelic Pucci of the 1970s to its ancient structured Persian ancestors and everything in between.

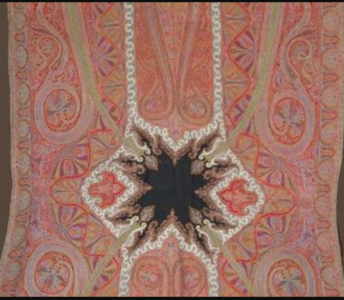

By the way, there is a great exhibition on at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in New York City called Design by Nature which has a fascinating section on the paisley motif - the introduction to which can be seen here. Anyway, five years ago when I was making my first foray into the design world, I met someone who learned I was a textile-mad biologist and said I should “be called Susy Paramecium not Susy Paisley” (a paramecium, in case you haven’t met one, is a tear-drop shaped microorganism). The idea for a paisley design based on real microorganisms popped into my head and I have been gently thinking about it ever since..

It has been a surprise to find myself falling in love with the tiniest creatures in Earth, having always studied big beasties like bears. I've been learning about organisms so small that millions can fit in a drop of water, and billions in a gram of soil. Microbes inhabit the widest range of habitats from sub-freezing temperatures, to water hotter than boiling, from lava, to the atmosphere miles above Earth, to glaciated mountain peaks and to the deepest ocean trenches. They include the strongest animals on Earth, the biggest producers of oxygen and greatest storers of carbon.

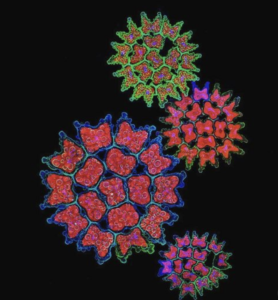

I wanted the design to evoke droplets of water as well as using the conventions of the paisley design. I also intended it to be reminiscent of stitching and lace, as the fabric of nature is fragile and intricately interwoven and embellished. I could exercise a bit of freedom in the colouration, and can further expand on this in the future, as many of these species are really quite transparent.

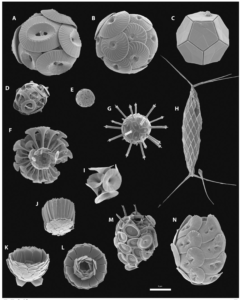

The species in my design are all aquatic - living in both fresh and sea water. They include many species of free-floating plankton, both zooplankton (more like animals) and phytoplankton (which are more like plants). Phytoplankton form the base of the marine food web. The health of all marine creatures, from fish fry to whales, is dependant the health of phytoplankton. They are also of serious conservation concern: warming oceans have caused levels of phytoplankton to decline 40% since 1950.

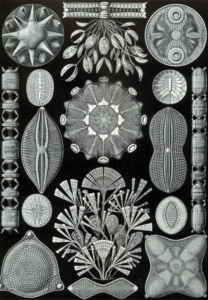

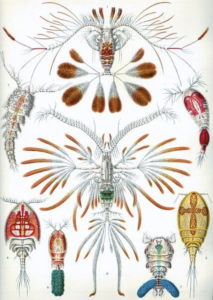

In my design, the swirls of what look like rice or tiny leaves are Euglena gracilis. It was the question of how to classify these particular "unclassifiable" beings with features of both plant and animals, that prompted early taxonomists like Ernst Haeckel to add a third living kingdom to Plantae and Animalia: the Kingdom Protista. Actually it was Ernst Haeckel’s stunning illustrations of copepods, diatoms, and nudibranchs that brought the beauty of these creatures to public awareness. (One of the colourways of this design is named after him.)

In with the Euglena are circular organisms: Prochlorococcus, a type of phytoplankton that releases countless tons of oxygen into the atmosphere. In fact they are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on the planet. Some scientists estimate that Prochlorococcus provides the oxygen for one in every five breaths we take. The design also includes the extraordinary forms of several species of diatoms, looking like cogs, spirals (Chaetoceros debilis) and fans (Licomopha flagellata) and other ornamented spheres (various cocolithosphores). The two pink forms are marine algae (Ptilota and Pterothamnion plumula). The long chains are marine algae: fragments of Spirogyra and a colonial diatom called Helicotheca.

The largest organisms in my design, yet still only a couple of centimetres in length, are aeolid nudibranchs. Facelina auriculata, was discovered by Müller in 1776, the year of American independence. These little beauties are very variable in colour with poetic common names like 'clown', 'splendid', 'dancer', and 'dragon'. Because their colouring is so variable, and in honour of 1776 and the American Independence, I whipped out my artistic license, and made my nudibranchs largely Red, White and Blue.

Around the centrals circles are unicellular paramecia (the paisley-shaped creatures), and amoebas. Also a water bear - a tardigrade. The rest of the creatures around that central circle are copepods - a group which, combined, forms the largest biomass on the Earth. And they are freakishly strong. Relative to their size, typically about 1mm long, copepods are also the world’s fastest animal, being able to jump at a rate of about a half a meter per second. Their incredible strength, relative to their size, makes them more than ten times stronger than any other known species on the planet and even stronger than any human-made motor produced to date.

They don’t only qualify as superheroes for their strength and speed. It is estimated that copepods absorb 1-2 billion tons of carbon per year. This makes them the largest carbon sink in the world, handily transporting massive amounts of carbon to the deep sea.

The whole living world relies on these beings, only 1% of which have been identified never mind appreciated. So this is my paisley tribute to these intriguing mini-miracles - so symmetrical and precise in form and yet totally bizarre - that are literally everywhere and yet invisible to the naked eye. Enjoy! Let me know what you think...