Sirens, mermaids, nudes and controversy

In my last look at John William Waterhouse’s life and artwork I am reverting to his love of mythological subjects and his love of women regaled in verse by well-known poets and story tellers. It was Waterhouse’s ability to depict beautiful women which made him popular with the public of the time.

In 1905 Waterhouse completed a work entitled Lamia. Although the name conjures up a gentle soul, it couldn’t be further from the truth. The word lamia means vampire, witch, sorceress, ghoul, or enchantress and the character emanates from Greek mythology. According to Greek myth, following the killing of Lamia’s children by the goddess, Hera, she sought vengeance by sucking the blood of men she seduced and devouring their children. Waterhouse was drawn to the subject through John Keats’ 1819 narrative poem Lamia. The poet however does not openly condemn the animal-woman as evil, but rather dwells on her beauty and the sexual excitement she offers. In the painting we see the foot of the soldier treading on the tail of the serpent Lamia and we see the scales she has shed wrapped around the back of her legs. These colourful scales contrast with her pale arms which she holds out towards the soldier. In all, Waterhouse completed three versions of this work, all around the same size. The original one, which was exhibited at the 1905 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, was purchased by Sir Alexander Henderson, Baron Faringdon, whose family members were keen patrons of Waterhouse.

Another of Keats’ maidens featured in a work by Waterhouse. In 1820 Keats penned his poem La Belle Dame Sans Merci (The Beautiful Woman without Mercy). It tells of a knight who meets a beautiful enchantress.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

The knight has fallen in love with this beautiful delicate creature but is she all that she seems? The knight is besotted and falls into a sleep and dreams of how he first met the female. However, in the knight’s dreams he is warned against a liaison with this beautiful maiden.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lullèd me asleep,

And there I dreamed—Ah! woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dreamt

On the cold hill side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Thee hath in thrall!

On waking from his sleep, he finds the maiden has gone and he is heartbroken. The setting for this work is a dense wood which symbolises both a sense of entanglement and moral confusion. Waterhouse’s painting is at the point in the poem when the knight meets the woman. He is depicted bending down towards her. He is totally bemused by her beauty as he looks at her upturned face. On the right sleeve of the woman there is a heart. She entraps the knight coiling her long hair around his neck like a serpent capturing its prey. She is tying her hair in a knot so as to entrap the knight. She pulls him towards her. She stares at him and he is lost, almost as if he has been hypnotised by her beauty. He has dropped his lance to the ground which metaphorically is a sign of his defencelessness, a powerlessness against her wiles and also symbolises a loss of his masculine virility. This beautiful sprite has emasculated him. It is a highly sensual work as we look upon the knight and the woman gazing into each other’s eyes. There is a tenseness about the depiction but as we know, once their lips meet, the knight will be lost. In a way Waterhouse’s depiction plays on the fears of men about their vulnerability at the hands of the fairer sex. It is also a statement regarding woman’s constant need to be loved.

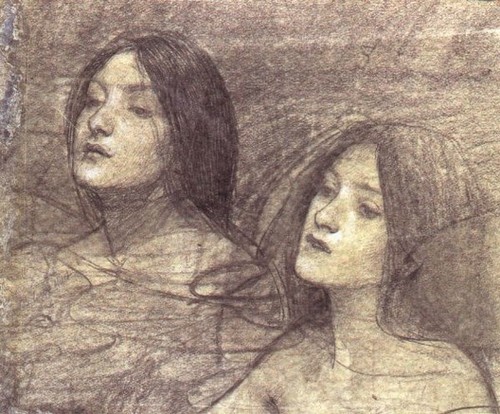

The interaction between males and females was of continuing interest to Waterhouse and he would often depict such interplay between the sexes by portraying mythological stories. In his 1896 he completed a painting entitled Hylas and the Nymphs, the setting of which is somewhere deep in an overgrown woodland surrounding a murky pond with its clumps of reeds and lilies. It is very reminiscent of the setting in John Everett Millais’ 1852 painting Ophelia. The depiction comes from the story of Jason and the Argonauts. Hylas, a very handsome youth, was one of Jason’s crew. When Jason’s boat landed on an island during his search for the Golden Fleece, Hylas was sent ashore to bring back some fresh water for the men. Hylas found a pool in a clearing and he reached down and put his pitcher into the water but before he could raise his pitcher, he looked up to discover water nymphs encircling him and we know that he is doomed. They were enticed by his beauty, and one of the nymphs reached up to kiss him. Immediately Hylas disappeared without trace, never to be found again and after a protracted search for his missing crewman, Jason decided to leave the island and continue with his travels.

The painting depicts the woodland pond in which we see the seven bare-breasted nymphs bathing, whilst, on the bank, we see Hylas kneeling down with his pitcher immersed in the water. There is a gentle sexuality about these captivating naked nymphs in the translucent water. Hylas’ olive skin tone is darker than that of the cream skin tones of the nymphs which contrasts with their dark hair. Although the legend describes Hylas as a very handsome man, our eyes immediately alight on the central nymph, who has hypnotised Hylas with her beauty and in some way has mesmerised us, the viewers of the painting. The painting was not complete by the time of the 1896 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and instead, was shown at the Manchester Autumn Exhibition, and was, following the event, purchased by the Manchester Corporation. They then allowed it to be displayed at the Royal Academy Exhibition in 1897. The painting was later loaned to a number of international exhibitions including the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle.

The painting was the centre of a controversy in 2018 when the curator of the Manchester Art Gallery decided to remove the painting from the walls of the permanent collection. What triggered the removal? Some believed because of the nudity on display in the work. The official stance was that removal of the painting was part of an art project by British Afro-Caribbean artist Sonia Boyce inspired by the MeToo and Time’s Up campaigns. A film of the removal of the picture was screened at the gallery with the intention being to inspire debate about the presentation of women ! There was an instant backlash from the public with regards this removal and the national press had a field day when the curator had to reverse her decision. The Daily Mail of February 5th 2018 splashed the headline:

Offensive nymphs are back on display at Manchester Art Gallery after backlash when artwork was taken over fear it was offensive to women.

Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs was taken down, it was ‘offensive to women’. A curator had claimed that the 1896 artwork perpetuated ‘outdated and damaging stories’ that ‘women are either femmes fatale or passive bodies’

A gallery accused of censorship after removing a pre-Raphaelite masterpiece for supposedly being offensive to women has made a humiliating U-turn.

After a furious backlash against Manchester Art Gallery for taking down John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs, the painting returned to pride of place over the weekend.

The Manchester Gallery had then to formulate a statement explaining the removal and subsequent return. Amanda Wallace, Interim Director Manchester Art Gallery, said:

“…We’ve been inundated with responses to our temporary removal of Hylas and the Nymphs as part of the forthcoming Sonia Boyce exhibition, and it’s been amazing to see the depth and range of feelings expressed. The painting is rightly acknowledged as one of the highlights of our Pre-Raphaelite collection, and over the years has been enjoyed by millions of visitors to the gallery. We were hoping the experiment would stimulate discussion, and it’s fair to say we’ve had that in spades – and not just from local people but from art-lovers around the world. Throughout the painting’s seven-day absence, it’s been clear that many people feel very strongly about the issues raised, and we now plan to harness this strength of feeling for some further debate on these wider issues…”

It is ironic that such a supposed declaration by the Manchester gallery that the painting was somewhat sexist and against feminist principles in the way it depicted naked women as the great Victorian painter and staunch supporter of feminism and women’s suffrage, and organiser of an exhibition of female artists for the Jubilee of Queen Victoria, Henrietta Rae, produced a similar painting in 1909.

In traditional folklore, the mermaid was looked upon as being a traditional siren who lured unsuspecting sailors to their doom with her mesmerising songs. She was half fish, half human and longed for the company of men. It was these legendary figures that inspired Waterhouse to complete a number of paintings featuring mermaids and sirens. In 1900 he completed the painting entitled A Mermaid which is now part of the Royal Academy collection. Waterhouse’s interest in this subject was because of its mystical temptress whose beauty and charisma proved deadly to men. Yet it was the mermaid’s inability to form a meaningful relationship with a human being that was in itself a curse which fated her to live an unfulfilled life. It could be that Waterhouse’s interest in this aspect was more to do with how men became anxious when confronted by an enchanting female as capitulating to such feelings could have a tragic outcome. In the painting we see a mermaid combing out her long red hair whilst singing a hypnotic song and by combining these elements Waterhouse is making the connection between the narcissistic trait of females with man’s vulnerability when it comes to beautiful women. Before the mermaid, there is a large shell containing pearls, which legend has it are formed by the tears of dead sailors. The mermaid is perched on a rock and her tail has coiled around her, almost as if she is hugging herself. Once again Waterhouse’s depiction could have been influenced by Tennyson’s 1830 poem, The Mermaid, with the lines:

Who would be

A mermaid fair,

Singing alone,

Combing her hair

Under the sea,

In a golden curl

With a comb of pearl,

On a throne?

That same year, 1900, Waterhouse completed a similar work entitled The Siren. This was his belated (by five years) Royal Academy Diploma Picture after being elected a full Academician in 1895. In this work Waterhouse has the mermaid perched on a rock and the shell we saw in A Mermaid painting has been supplanted by a musical instrument, the lyre. In The Siren, Waterhouse has depicted the siren looking down upon the drowning sailor. The expression on the siren’s face is somewhat mystifying as it is one of inquisitiveness and not one would expect from a “creature” who is about to watch the sailor drown in the raging sea. It is almost a look of compassion. The expression on the sailor’s face is one of pleading to be saved.

In 1915, John William Waterhouse was diagnosed as having liver cancer and two years later, he died at home on February 10th 1917 at the age of 68, and was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, London. Thirteen years after his death., his widow, through Christies, sold one hundred of her late husband’s works. Sadly, by that time, Waterhouse’s works had become unfashionable and his famous painting Ophelia was purchased for a meagre £450. However, by the 1960’s his work has become more popular and the postcard of his painting Lady of Shalott has become the Tate’s best-seller. His reputation was further enhanced in 2000 when his painting St Cecilia fetched £6.6 million at auction. It was the highest price ever paid for a Victorian painting. There was a major retrospective of his work at the Royal Academy in 2009 at which Waterhouse was described as:

“…one of Britain’s best-loved nineteenth century painters…”

In the exhibition catalogue which accompanied the exhibition, a biographer of Waterhouse wrote in the introduction:

“…Coursing through the pictures, across five decades, are Waterhouse’s fascination with melancholy, magic, and the thrilling dangers of love and beauty… they are lyrical in the truest sense of the word – imbued with the same hypnotic power possessed by the ancient poets who sang their stories. This was also a man particularly enthralled with female beauty and the power of women over men, over nature, over each other – no matter how sturdy or fragile they might appear physically…”

I have enjoyed every one of these Waterhouse posts and learnt so much. Thank you.

Hi…I’m trying to date a painting that I have from him…similar to sketch “Welsh Stream” sold at Sotheby’s. Any idea when he was in Wales? Is there a record of his trips there?

Thanks

Are you getting my comments?

Received your comments. Will try and find an answer for you when I am back in the country