October 2016

In the late 1950s, a shocking murder took place near a Royal Canadian Air Force base in south-western Ontario: the murder of 12 year-old Cheryl Lynne Harper. Lynne, as she was known, was the daughter of Flying Officer Leslie Harper, a supply officer posted to RCAF Station Clinton, and Shirley Harper.

On 9 June 1959, Lynne disappeared after being seen double-riding on a bike with one of her classmates, 14 year-old Steven Truscott, both of whom lived in the Permanent Married Quarters on base.

The two youths were last seen in the early evening of 9 June, riding along a county road just north-east of the base, heading towards Provincial Highway 8. Shortly afterwards, Truscott was seen riding along the same road back to the base. Truscott would later state that he dropped Harper off at Highway 8. Before riding off, he looked back and saw Harper getting into an unknown car.

Harper never returned home that evening and her father reported her disappearance to the Station Guardhouse at 11:00 pm.

The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) lead a search team of 250 military, civilian and police searchers in a frantic search to find Harper.

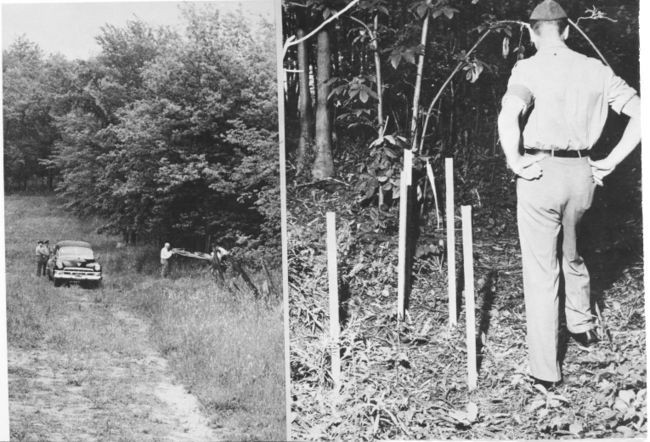

Two days later, on the afternoon of June 11, searchers discovered her body in a nearby farm woodlot owned by 23 year-old farmer Bob Lawson, known locally as Lawson’s Bush. Harper was partially nude and had been raped and strangled with her own blouse.

It was determined during the course of the very brief investigation that Truscott liked to spend time at Lawson’s farm to chat, help with the chores or play in the bush-lot, just like lots of other children in the area including Harper herself.

This didn’t bode well for Truscott, despite the fact Bob Lawson had gone to the guardhouse at base to report seeing a strange car parked near his fence line the night Harper disappeared, something that Truscott obviously didn’t have. The car was a convertible, possibly a 1952 Ford. Lawson stated that he and his neighbour Ross Crich had seen a man in the driver’s seat and what appeared to be a shorter girl beside him in the middle of the seat, neither of whom they recognized.

The officer on duty wasn’t interested and this lead was never followed-up. Lawson was told that a suspect had already been arrested and charged.

Truscott was quickly arrested and charged 2 days later by the lead investigator, OPP Inspector Harold Graham, a man who would later serve as Commissioner from 1973 – 1981. Graham’s insistence he had the right man after such a short and obviously deficient investigation would be one of the many criticisms of the case years later.

Graham’s investigation never explained how Truscott could have committed the rape and murder, yet he did not appear out of breath, sweating, scratched, his clothing in disorder or rattled in any way that might be expected of someone who had just committed such a crime. The night of 9 June was a warm night and Truscott would most likely have been profusely sweating if he had attacked and dragged Harper into Lawson’s Bush. It’s quite possible that he would have had some scratches on him or disordered clothing from Harper fighting back. None of the witnesses or police who interacted with Truscott in the hours afterwards noted anything amiss with Truscott, who seemed very calm.

Truscott was just as quickly convicted on 30 September 1959, just 3 months later in 15-day trial, despite little more than circumstantial evidence. He was sentenced to death by hanging, becoming the youngest person in Canadian history to be given a death sentance.

Primary among the evidence used to convict Truscott were the very controversial findings of the examining pathologist, Dr. John Penistan, linking Harper’s time of death to the time period Truscott was seen with her. Dr. Penistan came to the time of death by examining undigested food from Harper’s stomach, a finding that he concluded put Harper’s death at around the time Truscott was admittedly with her.

This theory is now-discredited. Even Dr. Penistan backed away from it when testifying at a Supreme Court hearing in 1966. In his re-assessment, Dr. Penistan now concluded that Lynne could have died up to 12 hours after her last meal.

Truscott’s sentence so shocked the government of John Diefenbaker that it was commuted to life imprisonment in February 1960.

During his incarceration, Truscott never wavered from professing his innocence, but his protests fell on deaf ears and his appeals were denied.

Truscott was paroled in 1969 and originally went to live with his parole officer and his family. Truscott, later moved to Guelph, Ontario, where he lived anonymously and worked as a millwright, a trade he learned in prison, under the name of Steven Bowers.

Truscott later married his wife Malene, with whom he raised three children. They remain married today.

It wasn’t until 2000, that Truscott re-emerged in an interview on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) investigative news program The Fifth Estate, which revived interest in his case.

In November 2001, an appeal was filed by the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted on behalf of Truscott and the following January, retired Quebec Justice Fred Kaufman was appointed by the federal government to review the case.

An appeal of Truscott’s conviction was heard by the Court of Appeal for Ontario beginning on 19 June 2006, a five-judge panel, headed by Ontario Chief Justice Roy McMurtry.

On 28 August 2007, Truscott was formally acquitted of the charges, although no declaration of innocence was made, something Truscott had hoped the court would announce, meaning he is still legally a suspect in the murder of Lynne Harper.

However, then-Attorney General of Ontario Michael Bryant officially apologized to Truscott shortly afterwards on behalf of the Ontario government for a miscarriage of justice.

Bryant also made it clear that the Crown would not be appealing Truscott’s acquittal.

Truscott’s acquittal didn’t sit well with Harper’s family, who have never thought that Truscott was innocent of the murder. In July 2008, Harper’s brother described Truscott’s $6.5 million compensation package as “a real travesty”.

So who killed Lynne Harper? There have been several other suspects that have come up over the years, including a convicted pedophile who had been stationed at RCAF Station Clinton at the time of Lynne Harper’s death. This suspect came to the attention of the OPP in 1997 from a retired police detective in London, Ontario.

However, none of the other suspects were taken very seriously by either the Ontario Provincial Police, who had jurisdiction over the murder since it apparently took place off the military base, or the RCAF Air Force Police, even years later as doubt in Truscott’s guilt began to surface.

“A VIABLE SUSPECT”

One very strong suspect was a man with a lengthy criminal history; a man whom author and retired Ontario Provincial Police Sergeant Barry Ruhl calls by the pseudonym of “Larry Talbot” to protect the privacy of “Talbot’s” family, even though he is now deceased.

In his book “A Viable Suspect,” Ruhl documents his 30-year investigation into the career criminal and alleged serial-killer, with whom he first came into contact with when the suspect broke into a cottage Ruhl and his fiancé (now wife) Pat were sharing in Sauble Beach in 1971. “Talbot” sexually assaulted Pat and shot Ruhl with a pellet gun after Ruhl chased him out of the cottage. Ruhl eventually caught up to him and arrested “Talbot” after a brief struggle.

Ironically for Ruhl, although he was a victim in this incident and might have died if the gun had been real, his superiors seemed quite concerned about the fact that he was sharing a cottage with a woman to whom he was not married. The fact that they were engaged may have helped Ruhl escape discipline for that “offence”.

Ruhl’s investigation of “Talbot” as a possible serial killer began in an official capacity and continued it “unofficially” after he had been removed from the case by his OPP superiors.

“Talbot” was known to drive a grey 1957 Chevy Bel Air, similar to the car that Harper allegedly got into when Truscott last saw her (possibly a 1959 Bel Air) and was also a traveling salesman whose company had contracts at RCAF Station Clinton, thus “Talbot” was known to frequent the Clinton area during the years of 1951-1959 and would have been familiar with the area.

Other evidence Ruhl cites in relation to “Larry Talbot” include the size of his shoes matching a shoe-print found at Lawson’s Bush, a sample of type A blood found at the scene (“Talbot” had type A), some other his idiosyncrasies and a “rape-kit” he kept in the trunk of his car.

Ruhl attempted to have “Talbot” declared a suspect in the Harper murder, even after he retired from the OPP in April 1994.

“Talbot” was a suspect in seven other unsolved homicides of young women in southern-Ontario that had similarities to them, ranging from the type of location of the crime scene where the bodies were found, to the neatness of the crime scene, to the abduction and/or crime scenes being areas “Talbot” was known to frequent or live. In fact, all of the crime scenes were located close to where “Talbot” lived at the time or within an easy drive.

“Talbot” was interviewed and investigated on several occasions by several other police officers, including by Halton Regional Police for the 1973 murder of Pauline Dudley, but nothing came of these efforts. Ruhl feels that “Talbot” was never properly investigated, particularly by the OPP, and this allowed “Talbot” to ultimately escape justice.

“Talbot” died on 3 September 2008, taking to the grave anything he knew regarding the unsolved homicides in which he was a suspect, including Lynne Harper.

“Talbot” certainly didn’t say anything to Ruhl when he called him out of the blue at home 2 months before he died and 37 years after their first encounter in Sauble Beach. “Talbot” wanted to complain about a Toronto Star article about the Harper murder that noted Ruhl had identified a suspect who was “A former salesman who drove a 1957 Chevy……” Although the article didn’t mention “Talbot” by name, he took enough offence to it to seek out Ruhl’s phone number. In an interesting and surreal “Last Call”, “Talbot” and Ruhl spent most of the conversation catching up like old buddies and even joked about their first encounter in Sauble Beach; that each of them got in a few good punches at the other.

TROUBLED AIRMAN WAS A KNOWN SEX OFFENDER

Another suspect in Lynne Harper’s murder who stands out is Alexander Kalichuk.

Born on 3 November 1923, Kalichuk was a Royal Canadian Air Force Sergeant who lived and worked in the area at the time of the murder. Sgt Kalichuk was known to be a heavy drinker with previous convictions for sexual offenses, some involving young girls.

Kalichuk served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II, but was released in 1945 and returned to civilian life.

In 1950, Kalichuk re-enrolled in the RCAF and was originally posted to RCAF Station Trenton, but soon after was transferred to RCAF Station Clinton, north of London, Ontario. Prior to leaving Trenton, Sgt. Kalichuk was twice convicted for indecent exposure in Trenton.

Kalichuk served at Clinton as a Supply Technician until 1955, when he released from the RCAF to take a civil service examination. Unsuccessful, Kalichuk returned to the RCAF and Clinton before the end of the year.

In 1957, Kalichuk transferred to RCAF Station Aylmer, about an hour away from Clinton. However, Kalichuk made frequent trips back to Clinton, where Lynne Harper’s father was the senior supply officer, as his residence was a 20-minute drive from the Clinton air station.

About three weeks before Lynne Harper’s murder, Kalichuk was arrested and charged by the Ontario Provincial Police for attempting to lure three young girls into his car outside St. Thomas, Ontario. The charge was dismissed shortly afterward (just 12 days before Lynne Harper was murdered) but the judge gave Kalichuk a warning regarding his behaviour.

On the same day Harper disappeared, 9 June 1959, air force medical officers held a discussion regarding Kalichuk’s drinking and behaviour. Around this time, Kalichuk’s probation officer advised air force officials of another incident of indecent exposure involving Kalichuk in the Town of Seaforth, not far from the Clinton base.

On 2 July, three-weeks after the murder of Lynne Harper, Kalichuk was hospitalized due to “overwhelming anxiety, tension, depression and guilt”, as reported in RCAF documents.

Police were warning about the activities of an unidentified molester who was preying on young girls from a car. Through all of it however, including the murder of 12-year-old Lynne Harper, Sgt Kalichuk managed to avoid particular attention as a suspect.

In 1959, Kalichuk had requested a transfer back to RCAF Station Clinton, but given the recent murder of Lynne Harper, senior officers at Clinton were worried about having a known sexual offender in their midst, thus he was posted to the nearby RCAF Station Centralia.

Sgt Kalichuk finally got his wish to return to RCAF Station Clinton in 1965.

Kalichuk drank himself to death in 1975. His final days were spent in a psychiatric hospital in Goderich, Ontario. A former RCAF veteran, who knew Kalichuk from his days as the base drunk at Clinton, was working at the same hospital. This man was shocked to see a disheveled and incoherent Kalichuk wandering the halls, apparently suffering the final stages of chronic alcoholism. He is buried in St James Cemetery, near Seaforth, Ontario.

The OPP has never confirmed whether Sgt Alexander Kalichuk was ever investigated regarding the murder of Lynne Harper.

CASE NOT CLOSED

The murder of Lynne Harper is still legally an open-case, as there is no statute of limitation for murder, but it’s one that is obviously very cold and likely will never be solved, not the least of which because most, if not all of the evidence that could lead to a conviction, is gone. Likely, only a confession will solve Harper’s murder now, but not one person has talked in the 57 years that have passed, not even from the grave in the form of a confession letter found by a relative.

In April 2006, Harper’s body’s was exhumed from her grave in Union, Ontario, in the very small hope that there might be some DNA evidence still on the body, an investigative tool not available to police in 1959. Not surprisingly, nothing was found on Harper’s remains due to the passage of time.

Another person who went to their grave leaving a lot of unanswered questions is retired OPP Commissioner Harold Graham. Author Julian Sher tried to interview Commissioner Graham while researching his book, “Until You are Dead — Steven Truscott’s Long Ride Into History,” but Graham always declined to be interviewed. Graham never answered many questions posed over the years from why he seemed so convinced that Truscott was guilty after such a myopic and questionable investigation, to why evidence that could have raised reasonable doubt, if not exonerated Truscott, was withheld from defence attorneys and the court?

Commissioner Graham died on 3 November 2001, not long after new evidence uncovered by Truscott’s wife Marlene, his lawyers and various journalists was presented to Justice Minister Anne McLellan. This information would lead to the review headed by Justice Kaufman 2 months later.

As a final note, David Yates, a reporter with the Goderich Signal Star points out, in an article published in the Signal Star on 4 January 2015, one of the greatest tragedies of the murder of Lynne Harper, other than her death:

“The most enduring tragedy of the Harper-Truscott case is that there will be no closure for the Harper family. There are no websites or organizations demanding justice for Lynne Harper. There is no monetary settlement for the Harper family to compensate for their half century of suffering. That, in the end, is the ultimate tragedy.”

Other sources on the Lynne Harper murder case:

“Who killed Lynne Harper?” by Bill Trent and Steven Truscott

“The Trial Of Steven Truscott” by Isabel LeBourdais

“Other leads on possible suspects”, Toronto Star, 29 August 2007 – The article that prompted “Talbot” to call Author Barry Ruhl at home in 2008. – www.thestar.com/news/canada/2007/08/29/other_leads_on_possible_suspects_ignored.html

“Murder was the Case” Podcast with Criminologist Lee Mellor and Barry Ruhl.

“Last chance for justice”, The Globe and Mail, 30 November 2001 – www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/last-chance-for-justice/article764574/

The episode of CBC’s news program The Fifth Estate featuring Truscott can be found on the CBC web site – www.cbc.ca/fifth/episodes/40-years-of-the-fifth-estate/steven-truscott-his-word-against-history

- Air Vice Marshal Hugh Campbell School, where both harper and Truscott attended school together, July 2011. Photo: Bruce Forsyth.

- The bridge that on Front Road that Harper and Truscott bicycled on before Truscott dropped her off at Highway 8, April 2017. Photo: Bruce Forsyth.

- The bridge that on Front Road where Harper and Truscott bicycled on before Truscott dropped her off at Highway 8. Witness Douggie Oates was at the far end of the bridge. April 2017. Photo: Bruce Forsyth.

- The river south of the bridge, where Gord Logan saw the pair bicycle across the road, April 2017. Photo: Bruce Forsyth.

- Highway 8 at the intersection of Front Road, where Truscott last saw Harper getting into a car, April 2017. Photo: Bruce Forsyth.

- Map showing important locations.

- Map showing important locations.

3 pings