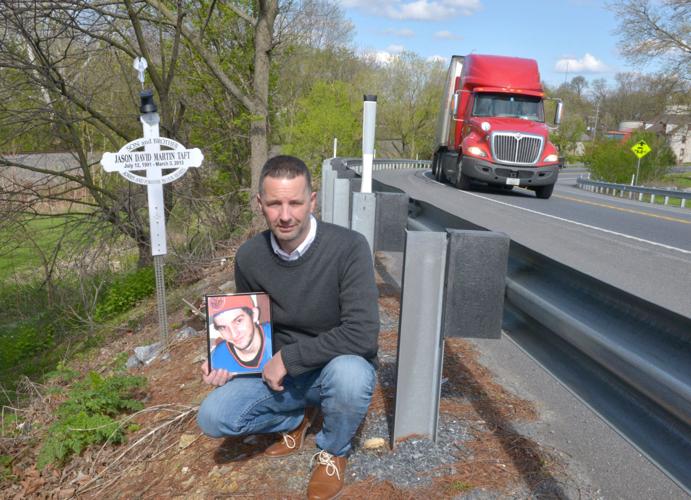

Motorists whiz by a 3-foot-high white cross, just behind a guard rail on a curve along Route 741 in Manheim Township.

It is hard for them to miss noticing the memorial marker Gary Taft erected where his 21-year-old son, Jason David Martin Taft, was killed in a vehicle accident two years ago.

That’s the point.

“I didn't want young Jason to be forgotten,” the Leola man said. “The cross helps sustain our memories of Jason, and our hope of seeing him again.”

Families often say such roadside memorials help them mourn and honor their lost loved ones.

State and local officials contend the often illegal markers create potential safety hazards to motorists and visitors, as well as a liability issue.

“It’s a delicate situation,” said Les Houck, 71, the second vice president of the Pennsylvania State Association of Township Supervisors, which represents nearly 1,500 townships. “There is no real easy answer. You have to take into consideration people are having grief and want to keep that there.”

Memorial markers can be dangerous, because motorists glance at them, and some stop to get a closer look.

Markers could also present a liability issue if they are struck, fly through a windshield and injure or kill someone, Houck said. The municipality or state could possibly be sued if they had allowed the marker to remain within their right-of-way.

Sacred to families

Kian Kianzad was 23 when he decided to drive home from a party on March 3, 2013 with his friend, Jason Taft, police said. Kianzad missed a turn and struck a tractor-trailer head-on, killing Taft. It happened along McGovernville Road (Route 741) near the Move In Self Storage business at 1250 Shreiner Station Road.

Gary Taft, 53, forgave Kianzad, but the Hempfield School District custodian thinks of his son, often.

“Having the cross made and erected where he passed somehow enabled me to be with him in spirit on that awful day and fellowship in his tragedy, pain, and his passing,” he said.

Taft said he wants the marker to prompt Jason’s friends to remember him. A spotlight makes the memorial visible at night. Taft had an angel on top of the cross but has since replaced it with a small solar cross, he said.

“I erected the cross because it is symbolic of my hope in resurrection,” Taft said. “It is symbolic of the hope I have that one day, I will see my son again.”

Taft said it did not cross his mind when he erected the cross in February 2014 to ask for permission, and PennDOT never asked him to move it.

Holly Fry, of Mount Joy, does not visit the roadside memorial for her 21-year-old daughter, Samantha Lynn Groff, who was killed when she crashed her car into a tree on Jan. 29, 2011.

Within a few days of the wreck on Musser Road in East Donegal Township, her daughter’s friends erected a cross at the tree. Fry’s family visited the memorial a few times with friends after the wreck, but Fry doesn’t return, and her regular travels do not take her past the cross.

“It’s really sad to go there...I miss and love her so,” Fry said. She prefers visiting Groff’s headstone in a cemetery on holidays and her daughter’s birthday.

Markers are common

Some memorials disappear over time. Others are maintained for years. No one can say how many there are.

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation spokesman Greg Penny said the number of roadside markers has not increased in the last 10 years, but did the previous decade.

Few markers dotted roadsides in southcentral Pennsylvania prior to 1990, and Mothers Against Drunk Driving posted most of them, Penny said. Markers became much more common by the late 1990s, Penny said.

Bill Stouch, 59, of Pedricktown, New Jersey, made and sold outdoor signs for 30 years before he created his first roadside memorial marker in 2012 for an employee whose cousin was killed in a crash.

Stouch took photographs of the PVC plastic memorial cross and created a Roadway Cross Memorials website. He has sold more than 200 markers to nearly every state and Canada. They cost $139 or $179, depending on the amount of engraving.

Most customers mark the site so friends remember their lost loved ones.

But not all. Stouch sold a marker to a woman in Georgia whose son was killed in an accident in which another man was driving.

“She just wanted it to remind the guy what he did,” Stouch said.

With each order, Stouch learns of another tragedy. One woman broke down so much, she had to call three times before completing the order.

“Some of the stories really rattle the soul,” he said, like a head-on collision that killed a Kansas mother and her three children on their way to school.

“I had to do four crosses, three small ones and one regular size,” Stouch said.

Threat to safety

It is illegal to install, erect or place even a temporary sign on PennDOT right-of-way, Penny said. PennDOT must grant permission for such markers, and they must follow state highway law, the vehicle code and PennDOT regulations.

Officials made them illegal to minimize driver distractions and obstacles.

“We try to keep the roadside clear of objects motorists can hit,” Penny said. “They are a potential safety issue as soon as they are installed.”

When motorists report something interferes with sight distance or distracts them, PennDOT removes the marker if it is a safety problem, he said. County maintenance crews take such markers to a stockpile area where the person who installed it can reclaim it.

PennDOT also removes any memorials in the way of mowing or shoulder cutting, Penny said. If a roadside marker doesn’t create an immediate safety hazard, PennDOT generally doesn’t remove it right away.

“We realize people need time to grieve,” Penny said. “But they are not permanent memorials, and they may be removed at any time.”

Some people object to crosses being used as roadside memorials, Penny added. They contend a state allowing a cross within its right-of-way supports Christianity in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

Townships don’t have as many issues with roadside markers as the state, according to Houck, who has served Salisbury Township for 36 years, currently as an elected supervisor and secretary-treasurer.

Townships have smaller right-of-ways, as little as five or six feet on either side of rural roads, and families don’t put many markers along the roads because they have less traffic.

Townships sometimes ask families to keep markers 10 feet off the road, according to Stouch.

“Most people tell me they go on county roads and usually, no one bothers them,” he said. “They don’t rip them down. They even mow around them.”

The New York Times in 2009 reported on whether roadside memorials should be banned.

Other options

Penny encourages people to find other ways to express their grief and memorialize someone who has died, such as contributing to a memorial fund, planting a tree or adopting a road.

Many years ago, a woman from New York wanted to erect a granite memorial in the right-of-way along Route 283 in Dauphin County where her husband and two children died in a fiery truck crash, he said. Penny had to deny her request for safety’s sake.

PennDOT also halted a threat to safety along another interstate highway in Dauphin County, he said. A person was occasionally stopping along the road to mow around a memorial.

By RYAN ROBINSON | Staff Writer

By RYAN ROBINSON | Staff Writer