“No man, however courageous he may be, likes to face a resolute woman with a hatpin in her hand.”

When you think of fashion, you probably think of a variety of things. Superfluous trends, silly styles, strange catwalk concoctions. However, whilst fashion has been ridiculed for centuries, over many periods of history fashion has been used as a tool of liberation, particularly for women.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a revolution was happening amongst Western women. The idea of women’s suffrage had been circulating for a while, and was beginning to pick up traction. Whereas in the past, women had not generally been allowed out unescorted, but had to have a man or ‘sensible’ older female relative go out with her, women began to decide it was their right to explore the world on their own. Previously, men would court women from the confines of her home where a beady eye could be kept on the pair, but now young men and women would go out for dates, to the theatre, a show, or a walk around the park. Women began to taste real freedom and independence.

Edwardian hatpins’ primary purpose was to hold hair and hats in place. The ends were often highly decorated with jewels to make the ensemble even more attractive. Image source.

The downside of this for many women, however, was the predatory men who lurked in the world. Now that women began to walk the streets or take public transport alone, they were more vulnerable to the advances of lecherous men who felt more emboldened to take a risk. Just as many women today know of handsy men in a crowded underground, so too did women of the early 1900s begin to experience men who would take advantage of a dark tunnel or a lurch in the carriage to place their hands in unwanted places. There was even a slang term – mashers – used to describe these predatory men.

Luckily for women, a change in fashion was to be their salvation. Upon the dawning of the Edwardian period (1901 – 1910), it became fashionable for women to grow their hair long so that they could put them up into huge hairstyles. This was then coupled by ever-growing hats which were as elaborate as they could be, covered in ribbons, feathers, fruit, and often an entire bird. Clearly, these huge hairstyles and hats were difficult to keep in place, and so large hatpins were used to keep everything in place. As the styles grew, so did the hatpins, with many pins reaching over 10 inches long. After some instances of innocent bystanders being accidentally pricked and injured with stray hatpins, women caught on to something – these fashion items were a convenient weapon of self-defence.

Vintage postcards showing some (perhaps more elaborate than the reality – but not always!) examples of the large fashionable hats of the period.

A perhaps more realistic portrayal of the fashion for large hats with long feathers from this 1910 Edwardian card.

One of the early recorded examples of the use of hatpins to ward against unwanted advances by men come from Leoti Blaker, a woman from Kansas who was visiting New York in 1903. As the story was recounted in the New York World, Leoti got onto a stagecoach on Fifth Avenue on an afternoon in May which was typically crowded. As the coach jostled and rocked about, she noticed that the well-dressed man of about fifty who was sitting next to her was starting to draw closer to her, causing her to edge into a corner. Eventually, this man put his arm around her back, and this was the last straw for Leoti:

“I became so enraged that I didn’t know what to do. At last I reached up and took a hatpin from my hat. I slid it around so that I could give him a good dig, and ran that hatpin into him with all the force I possessed… he let out a terrible scream of pain… but he didn’t have a word to say. He just got up and left the coach at the next corner.”

The account of Leoti’s experience in The Evening World (New York, New York) 27 May 1903, Page 3 via Newspapers.com.

Leoti’s experience wasn’t atypical of a woman at that time, but neither was her response. All over the Western world stories were pouring in of women who had defended themselves or others from assailants by using their hatpins. Hatpins were an excellent choice of self-defence as they were easily accessible, sharp enough to cause severe pain to deter the attacker, but as they were usually used to stab a man on his wrist or arm it was unlikely to cause serious damage. However, it also had that possibility to do severe damage if thrust at the face or neck, and so was often sufficient to scare him away. It is not for no reason that future President Theodore Roosevelt said “no man, however courageous he may be, likes to face a resolute woman with a hatpin in her hand”.

As may be a familiar tune to the ears of women today, some men – indignant at the attacks – sought to place blame on the women. The Chicago Vice Commission suggested that if unchaperoned women wished to avoid unwanted attention then they should dress as modestly as possible. For the most part, however, women who fought against harassers were considered heroes. There was an explosion in reports of heroic women using their hatpins, fiction novels lauded their heroines who used hatpins to preserve their honour, and numerous newspapers began to circulate pictures and articles on how to use hatpins to protect yourself. It wasn’t just hatpins that could be used – many suggested using an umbrella, at this time sharp, steel-tipped rods that were carried at all times of day by women.

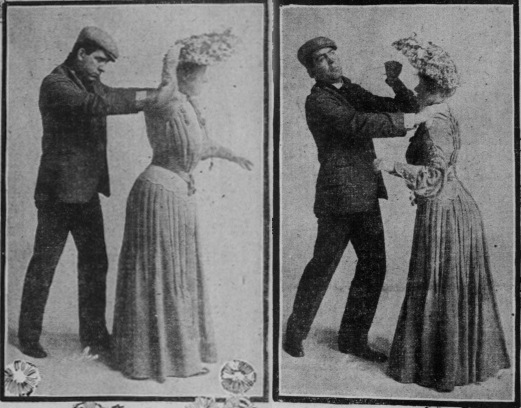

Photographs from the San Francisco Sunday Call, 1904, demonstrating how women could extract their hairpins to defend against an attacker. Pictures showing how women could use umbrellas to defend themselves can be found at The Chicago Tribune here.

This ability to defend oneself was a revolution for women. Now they did not need to fear this new freedom from restrictions and chaperones – if a man got inappropriate, he would swiftly meet the sharp end of a fashion item. These were not sparse, one-off incidents that were blown out of proportion by reporting – these incidents were happening on a daily basis and, as is to be expected, men in power started to get uncomfortable. At a meeting in Chicago in 1910 debating an ordinance that would ban hatpins longer than nine inches, one supporter cried “If women care to wear carrots and roosters on their heads, that is a matter for their own concern, but when it comes to wearing swords they must be stopped”. Nan Davis summed up the feelings of women everywhere (and probably of many reading this today): “If the men of Chicago want to take the hatpins away from us, let them make the streets safe. No man has a right to tell me how I shall dress and what I shall wear.”

Nan Davis, and her fight for the right for women to keep their hatpins. Chicago Tribune.

By the end of the Edwardian period, lawmakers everywhere were making attempts to limit the damage of hatpins (usually to unsuspecting, innocent bystanders). Across various states of the US, the length of hatpins were regulated, and in many countries women were told to place corks or other protectors on the end of pins so that they could not accidentally hurt passers-by. In Australia, fines were introduced for those wearing dangerous hatpins, and in 1912, 60 women in Sydney went to jail rather than pay the fines. Women everywhere protested in solidarity with their sisters who were having hatpins regulated, with conservative women in London refusing to buy protectors for the points of their pins. In many cases, however, the enforcement of these rules were ineffectual. Policemen didn’t feel able to approach women in the streets to enforce the laws, and many men sympathised with women’s plight. An article from 1917 in the Chicago Day Book told their male readers that instead of trying to get women arrested for their hatpins on public transport, “Far be it from us to pick on the ladies. Let’s try and see that they all get a seat so they won’t have to swing around on a strap.”

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Despite the date of this last article, in reality the dangers of the hatpin generally subsided with the First World War. The needs of war tended to mean that fashions became less flamboyant, and by the 1920s the new flapper fashion of short, bobbed hair and cloche hats took over, eliminating the need for these huge hatpins.

Suffragette protesters had already been training themselves in martial arts to protect themselves at rallies, and hatpins were just another weapon in their arsenal. 1910 Punch cartoon.

Something as small (or not, as the case became) as a hatpin really did liberate women in the early 1900s. It allowed them to feel safer to travel alone, giving them a freedom not experienced for generations. Suffragettes used them to defend themselves at protests, and a hoard of would-be-sexual assaulters, robbers, and various other assailants were swiftly rebuffed by women everywhere. The fact that women felt emboldened enough to use these weapons, and to actively use them to threaten those who may cause harm was in itself a revolution for women’s confidence everywhere, and fed into the growing calls for women to have recognised rights in society, particularly the right to vote. Women were no longer delicate objects who had to be taken everywhere and have a constant eye on them, but strong, independent, intelligent, feisty people who were in charge of their own destiny. For this, hatpins will always have a fond place in my heart.

Actress Émilie Marie Bouchaud daring you to try and attack her before she reaches for her hatpin.

Previous Blog Post: Royal People: Anna Komnene – Historian, Physician, Byzantine Princess

Previous in Historical Fashion: Georgian Women’s Hairstyles

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/hatpins-mashers-self-defense-history-women-hats-fashion

http://www.bartitsu.org/index.php/2010/07/the-sting-of-a-hornet-edwardian-hat-pin-self-defence/

Great post!

LikeLike

Thanks a lot!

LikeLike

Well done! Love the old photos too! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes there were so many great ones to choose from it was difficult to not just put a hundred!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting and informative post.

I think, though, that it was only women of a more privileged strata of society who were not ‘allowed out unescorted’ for the first time in the Edwardian period. Women further down the social scale had been out and about for centuries, facing similar problems,as they went about their daily business as servants and at other work.

There is an entry in Samuel Pepys diary which shows a young 17th century woman defending herself in just this way, though possibly not with a hat pin.

LikeLike

Yes that is very true – lower class women had to be out and about alone because of their work!

How interesting! Thank you so much for sharing that. I didn’t know Pepys was such a cad! But very interesting to see that it was an age old technique.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is hilarious. It’s cool to know that women in the past were just as scrappy and resourceful as women today.

LikeLike

Interesting to think of the hatpin as a potential weapon!

LikeLike

Yes indeed – but you can see how it would have been effective!

LikeLike

I have worn hats with a large hat pin for over 40 years. They are beautiful with ornate tops. Haven’t had to use one as a weapon …… yet! Great post! Thanks very much!

LikeLike

They do lend themselves to beautiful hats. It’s a shame hats aren’t really worn any more! Glad you haven’t had to use it on any naughty men – but good to know you could! Glad you enjoyed the post.

LikeLike