Home | Category: Ocean Fish

FLYING FISH

Flying fish are bony, ray-finned fish with wing-like pectoral fins. Despite their name, flying fish aren’t capable of powered flight and don’t really fly like birds. Instead they propel themselves out of the water at speeds high speeds and, once in the air, extend their rigid “wings” and glide for up to 200 meters (650 feet). The highly modified pectoral fins are primarily for gliding — the fish hold the fins flat at their sides when swimming. At those times they look like a regular herring-type fish. They have very streamlined bodies, which reduce drag when the fish are gliding. [Source: National Wildlife Federation, Wikipedia]

Pigeon-size flying fish can make powerful, self-propelled leaps out of the water and long wing-like fins enable to glide for long distances above the water's surface. The main reason for this behavior is thought to be to escape from underwater predators such as swordfish, dolphins, mahi mahi, mackerel, tuna, and marlin, But their periods of flight make them vulnerable to attacks by frigate birds and other avian predators.

Flying fish are found tropical and subtropical — and to a lesser extent temperate — waters all over the globe. They are commonly seen in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans and off both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States. Open oceans, often not so far from coastal areas, are where most flying fish live, but some live on the outskirts of coral reefs. Flying fish live in all of the oceans, particularly in tropical and warm subtropical waters. They are commonly found in the epipelagic zone, the top layer of the ocean to a depth of about 200 meters (656 feet).

Related Articles: FISH: TYPES, HISTORY, HABITATS, BIODIVERSITY, DEFINITIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FISH CHARACTERISTICS: ANATOMY, BREATHING, DIGESTION, SPEED, BITING POWER ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FISH BEHAVIOR, SLEEP, PAIN AND SCHOOLING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FISH PERCEPTION AND COMMUNICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FISH REPRODUCTION, MATING, DEVELOPMENT AND PARENTING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Flying Fish Taxonomy and History

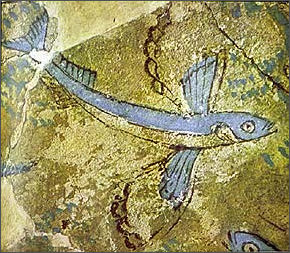

flying fish from ancient Minoa, over 3,000 years old The oldest known fossil of a flying or gliding fish are those of the extinct family Thoracopteridae, dating back to the Middle Triassic, 235–242 million years ago. However, they are not related to modern flying fish. The wing-like pectoral fins evolved convergently in both lineages.

Flying fish occupy the Exocoetidae are a family of marine fish in the order Beloniformes class Actinopterygii. The term Exocoetidae is both the scientific name and the general name in Latin for a flying fish. The suffix -idae, common for indicating a family, follows the root of the Latin word exocoetus, a transliteration of the Ancient Greek name that literally means "sleeping outside". so named as flying fish were once though to leave the water to sleep ashore, or perhaps due to flying fish flying and thus stranding themselves in boats. [Source: Wikipedia]

Species of genus Exocoetus have one pair of fins and streamlined bodies to optimize for speed, while Cypselurus spp. have flattened bodies and two pairs of fins, which maximize their time in the air. The term Exocoetidae is both the scientific name and the general name in Latin for a flying fish. The Latin word exocoetus is a transliteration of the Ancient Greek name that literally means "sleeping outside", so named because flying fish were believed to leave the water to sleep ashore because of their habit flying onto and stranding themselves in boats.

From 1900 to the 1930s, flying fish were studied as possible models used to develop airplanes. The Exocet missile is named after flying fish as some types are launched from underwater, and break the water surface, skimming just above it, before striking their targets.

Flying Fish Species and Taxonomy

There are 65 species of flying fish grouped in seven to nine genera. They vary in length from five to 46 centimeters (2 to 18 inches). Most have a blue topside, camouflage against birds looking down from above, and silvery undersides, protection from fish looking upwards. Some flying fish also have winglike pelvic fins that help them to glide. These species are called four-winged flying fish.

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii

Order: Beloniformes

Suborder: Exocoetoidei

Superfamily: Exocoetoidea

Family: Exocoetidae

The Exocoetidae is divided into four subfamilies and seven genera:

Subfamily Exocoetinae Risso, 1827

Genus Exocoetus Linnaeus, 1758

Subfamily Fodiatorinae Fowler, 1925

Genus Fodiator D.S. Jordan & Meek, 1885

Subfamily Parexocoetinae Bruun, 1935

Genus Parexocoetus Bleeker, 1865

Subfamily Cypsellurinae Hubbs, 1933

Genus Cheilopogon Lowe, 1841

Genus Cypselurus Swainson, 1838

Genus Hirundichthys Breder, 1928

Genus Prognichthys Breder, 1928

Flying Fish Physical Characteristics

A number of morphological features give flying fish the ability to leap out the ocean and skim above its surface. One such feature is fully broadened neural arches, which act as insertion sites for connective tissues and ligaments in a fish's skeleton. Fully broadened neural arches act as more stable and sturdier sites for these connections, creating a strong link between the vertebral column and cranium. This ultimately allows a rigid and sturdy vertebral column (body) that is beneficial in flight. [Source: Wikipedia]

Having a rigid body during glided flight gives the flying fish aerodynamic advantages, increasing its speed and improving its aim. Furthermore, flying fish have developed vertebral columns and ossified caudal complexes. These features provide the majority of strength to the flying fish, allowing them to physically lift their bodies out of water and glide remarkable distances. These additions also reduce the flexibility of the flying fish, allowing them to perform powerful leaps without weakening midair.

The curved profile of the "wing" is comparable to the aerodynamic shape of a bird wing. The flying fish’s unevenly forked tail has a top lobe that’s shorter than the bottom lobe. Flying fish can be up to 45 centimeters (18 inches) long, but average 17 to 30 centimeters (7 to 12 inches).

Flying Fish Flying

Flying fish “fly” by stretching out their pectoral fins like wings and gliding above the water. They become airborne after they propel themselves out of the water at speeds of more than 56 kilometers per hour (35 miles per hour). Once in the air, their rigid “wings” allow them to glide for up to 200 meters (650 feet).

Flying fish generally stay aloft for 2 to 15 second and glide from 45 to 200 meters. A typical flight is around 50 meter (160 feet), By periodically dipping their tail into the sea and wiggling it pack and forth for extra propulsion they can glide for more than 300 meters (1,000 feet). The fish can use updrafts at the leading edge of waves to cover distances up to 400 meters (1,300 feet)

Flying fish fly when pursued by predators such as dolphins, sharks or tuna, and sometimes it seems simply for the sheer joy of doing it. They leap from the water and glide along supported by air currents found above the sea. Their “wings” are pectoral fins on either side of the fish. They act like the wings on a glider.

In May 2008, a Japanese television crew (NHK) filmed a flying fish (dubbed "Icarfish") off the coast of Yakushima Island, Japan. The fish spent 45 seconds in flight. The previous record was 42 seconds. Flying fish can travel at speeds of more than 70 km/h (43 mph). Maximum altitude is 6 meter (20 feet) above the surface of the sea. Flying fish often accidentally land on the decks of small boats. [Source: Wikipedia].

How Flying Fish Fly

Flying fish flight is achieved through the following steps: 1) powered by it tail the fish accelerates near the water surface; 2) the large lower tail lobe moves sideways to propel the fish above the water surface; and 3) large pectroal and pelvic fins harden and help the fish glide as high as a meter and typically a distance of about 10 meters

To take off, flying fish need to attain enough speed. They do this by moving fast in the water with their pectoral fins against their bodies. When enough speed has been attained, usually around 35 mph, it leaps from the surface with a couple of sharp swishes of its tail and takes off by extending its pectoral fins.

When in the air flying fish spread their elongated pectoral fins which before then had been tucked closely against the body. Air catching the membranes of the fins lift the fish like the wings of a bird. Sometimes as they fly they dip their tails into the water, beat it a few more times and extend their flights.

Flying fish are able to increase their time in the air by flying straight into or at an angle to the direction of updrafts created by a combination of air and ocean currents. At the end of a glide, they fold their pectoral fins to re-enter the sea, or drop their tails into the water to push against the water to lift for another glide, possibly changing direction.

Flying Fish Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Flying fish eat a variety of foods, but feed mainly on plankton. They sometimes eat small crustaceans. Predators include dolphins, tuna, marlin, birds, squid, sharks and porpoises.

Spawning takes place near the surface in the open ocean. A female deposits eggs, which are attached by sticky filaments to seaweed and floating debris. Newly hatched flying fish have whiskers near their mouths, which disguises them as plants, thus protecting them from predators. A flying fish lives for an average of five years. [Source: National Wildlife Federation]

Many flying fish live only around a year. Young flying fish may have filaments protruding from their lower jaws that camouflage them as plant blossoms.

Flying Fish Fishing and Human Food

Flying fish populations are stable. They fish are commercially fished in some places In Japan, Vietnam, and China they are caught by gillnetting, and in Indonesia and India by dipnetting.. Flying fish are attracted to light and are relatively easy to catch because of their tendency to leap into small, well-lit boats. [Source: National Wildlife Federation]

In Japanese cuisine, flying are often preserved by drying to be used as fish stock for dashi broth. The roe of Cheilopogon agoo, or Japanese flying fish, is used to make some types of sushi, and is known as tobiko. It is also a staple in the diet of the Tao people of Orchid Island, Taiwan. Flying fish roe is known as cau-cau in southern Peru, and is used to make several local dishes. They are also eaten in Bangladesh. [Source: Wikipedia]

People say the taste of flying fish is close to that of sardines. In the Solomon Islands, the fish are caught while they are flying, using nets held from outrigger canoes. They are attracted to the light of torches. Fishing is done only during nights when there is no moonlight.

Flying Fish and Barbados

Barbados is known as "the land of the flying fish", and the fish is one of the national symbols of the country. Many aspects of Barbadian culture feature flying fish;. They are depicted on coins and stamps, as sculptures in fountains, in artwork, and as part of the official logo of the Barbados Tourism Authority. The Barbadian coat of arms features a pelican and dolphinfish on either side of the shield, but the dolphinfish resembles a flying fish. Artistic renditions of flying fish and holograms of them are present in the Barbadian passport. [Source:

Flying fish is part of the national dish of Barbados, cou-cou and flying fish. Flying fish are favorite snack and meal and can be bought at roadside stand as well as at five-star hotels. The Waterfront Cafe in the Barbadian capital, Bridgetown serves cou-cou, consisting of flying fish steamed in broth and served with cornmeal and okra mush.

flying fish Barbados-style, from Bajan Things bajanthings.com/bajan-flying-fish

Flying fish were once abundant in Barbados waters as they migrated between the warm, coral-filled Atlantic Ocean surrounding the island and the plankton-rich outflows of the Orinoco River in Venezuela.

Carol J. Williams wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Barbados has built an industry on the creature. At least 15 percent of its work force is employed in fisheries. The annual catch of more than 2,200 tons is sold to wholesalers for $2.6-million, the island's most important source of income after tourism. Every restaurant and snack shack on this island offers some rendition of the flying fish, from a 75-cent sandwich to pan-seared, aioli-drizzled entrees that fetch up to $35 in upscale resorts. [Source: Carol J. Williams, Los Angeles Times, December 19, 2004]

Sherwin Moseley earns a living cleaning flying fish. Processors such as Moseley have developed an art of removing the tiny bones from flying-fish fillet. And local fishermen have honed trapping skills, luring the fish to the surface during spawning season with fish-attracting devices such as floating palm fronds or sugar cane scraps on which they leave their eggs.

Flying Fish Move From Barbados

In in recent years flying fish have shifted their migrations and are not as abundant as they once were in Barbados waters. As of the early 2000s, the Atlantic flying fish was found about 200 kilometers (125 miles south) — off the coast of Trinidad and Tobago — from where it used to be most abundant.

Some say environmental problems are at least partly to blame. Barbados has had an increase of ship visits as the island was become more closely linked to the rest of the world. Coral reefs around Barbados have suffered due to ship-based pollution. Barbadian overfishing has pushed the fish closer to the Orinoco delta and many don’t return to Barbados water. Today, most flying fish only migrate as far north as Tobago, around 220 kilometers (140 southwest of Barbados. [Source: Wikipedia]

Reporting from Barbados, Carol J. Williams wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Their departure has idled thousands of fishermen here, imperiled the economy and bruised national pride. The decline has made a ghost town of the Oistins fish market in Barbados, where snack shops are shuttered and only a smattering of hawkers have anything to sell.Oistins fish vendor Lucy Clark, 69, says, "The fishermen aren't working. The boats aren't shoving off. It's the worst I've seen in my 50 years here." [Source: Carol J. Williams, Los Angeles Times, December 19, 2004]

Flying Fish Dispute Between Barbados and Trinidad

In 2006, the council of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea fixed the maritime boundaries between Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago over the flying fish dispute, which had raised tensions between the neighbouring islands. The ruling stated both countries must preserve stocks for the future. Barbadian fishers still follow the flying fish southward. [Source: Wikipedia]

Williams wrote in 2004: Flying fish are so central to Barbados culture that fishermen here insist they have the right to harvest the stock wherever it might stray. Fishermen pursued the fish into Tobago's waters at the end of last season, setting off a diplomatic snit that continues to roil Caribbean relations. Two trespassing ship captains were arrested in February. Boatloads of fish were seized. Strongly worded diplomatic missives were exchanged. [Source: Carol J. Williams wrote in the Los Angeles Times, December 19, 2004]

Now, as a new five-month fishing season gets under way, high dudgeon prevails across the teal blue waters separating the two former British colonies. Trinidadian officials have promised to defend their territory "in the strongest possible way" against further intrusions. Barbados has appealed to a United Nations maritime panel to settle the dispute. And Bajans, as the locals here are called, are shut out of the catch till at least 2006, while the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea deliberates, compelling them to buy fish from the neophyte fleet in Tobago.

Moseley said it pains him to receive the imported catch from Tobagonian fishermen, many of them trained by Bajans in the bygone days of friendly collaboration. "They don't know how to filet them properly," said the dreadlocked Moseley, slapping the back of one hand into the palm of the other to punctuate his disappointment. "When we get them in from Trinidad, we have to clean and bone them all over again."

Many Bajans resent Trinidad for not allowing them to fish in its waters. With its vast oil and gas reserves, Trinidad does not need to grab the strayed stock that is vital to Barbados' cuisine, economy and identity, Bajans say. "The Trinidadian doesn't even like flying fish. He never caught them before they moved into the warmer waters," said Norman Carter, who has piloted boats to the north coast of Tobago for 34 seasons — until this one. "They just want to catch our fish to sell back to us. It's just a market to them."

Officials in Port of Spain, capital of Trinidad and Tobago, contend that Barbados fished out its share of the stock, and make no apologies for treating flying fish as a resource rather than someone else's national icon. "The stocks in Barbados waters have been grievously depleted, and we didn't want a large number of vessels from the Barbados fleet, the largest in the region, descending on our waters," said Gerald Thompson, legal officer at the Foreign Ministry, explaining why the Trinidadian coast guard began apprehending Bajan captains.

But Hazel Oxenford, a fisheries biologist at the Center for Resource Management and Environmental Studies at the University of the West Indies in Barbados, says such talk of one side overfishing a mobile stock is "nonsense." "Fish move, and they don't recognize boundaries," said the professor, who has been appointed to provide scientific expertise to the arbitration panel.

Oxenford, a Bajan, says that she is "on the side of the fish" and impartial in the squabble. She likens the flying-fish stock to a herd of cows moving from one farmer's land to another's. Oxenford said the U.N. panel will not deal specifically with the flying-fish feud but will delineate each state's maritime boundary and rights to all the resources within it, including natural gas and oil. Such boundaries are usually fixed at the halfway point between maritime states. The flying fish, which live only a year, spawn in waters about 120 miles from Barbados and less than 30 from Tobago.

Still, Bajans back their government's decision to get an international ruling in the matter. Some lovers of flying fish say the territorial tiff has had no effect on either supplies or interisland relations. "It's an intergovernment thing. I don't think it has anything to do with the (common) man," said Jennifer Slocombe, manager of the Waterfront Cafe in the Barbadian capital, Bridgetown,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023