HESSE | WILKE: A CHRONOLOGY

MATERIALS

HESSE | WILKE: A CHRONOLOGY

MATERIALS

Found materials are central to Hesse’s early sculptures. After August 1967 and her discovery of latex at Cementex on Canal Street, her work shifts. This material, which encompasses a shift from liquid to solid, brings diversity to her work. She begins to make her own planes and shapes, and to explore anew the relationship between tension and flex that rope and string, in its various manifestations, had previously allowed. This concern for a material that can be both malleable and solid also appeals to Wilke, who uses latex, as well as ceramic, gum, and rubber for her sculptures. Wilke in 1974 acquires a loft on Greene Street in Soho, and also finds materials on Canal Street, some at the celebrated art supplier Pearl Paint. She orders latex from General Supply and Chemical Corporation in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Both artists exploit the skin-like effects of latex and play with the different textures that can be achieved with the material. More broadly, both artists are interested in playing with the surfaces of their sculptures, experimenting with color and glaze, as well as the raw effects. This attention to materials provides a hinge that connects both Hesse and Wilke to other artists interested in process. If Hesse is now better known as a “Process Artist,” together with Richard Serra and Robert Morris, Wilke insists on the importance of her own process as a primary frame for understanding her artworks, as demonstrated in her description of works like the one-fold gestural sculptures.

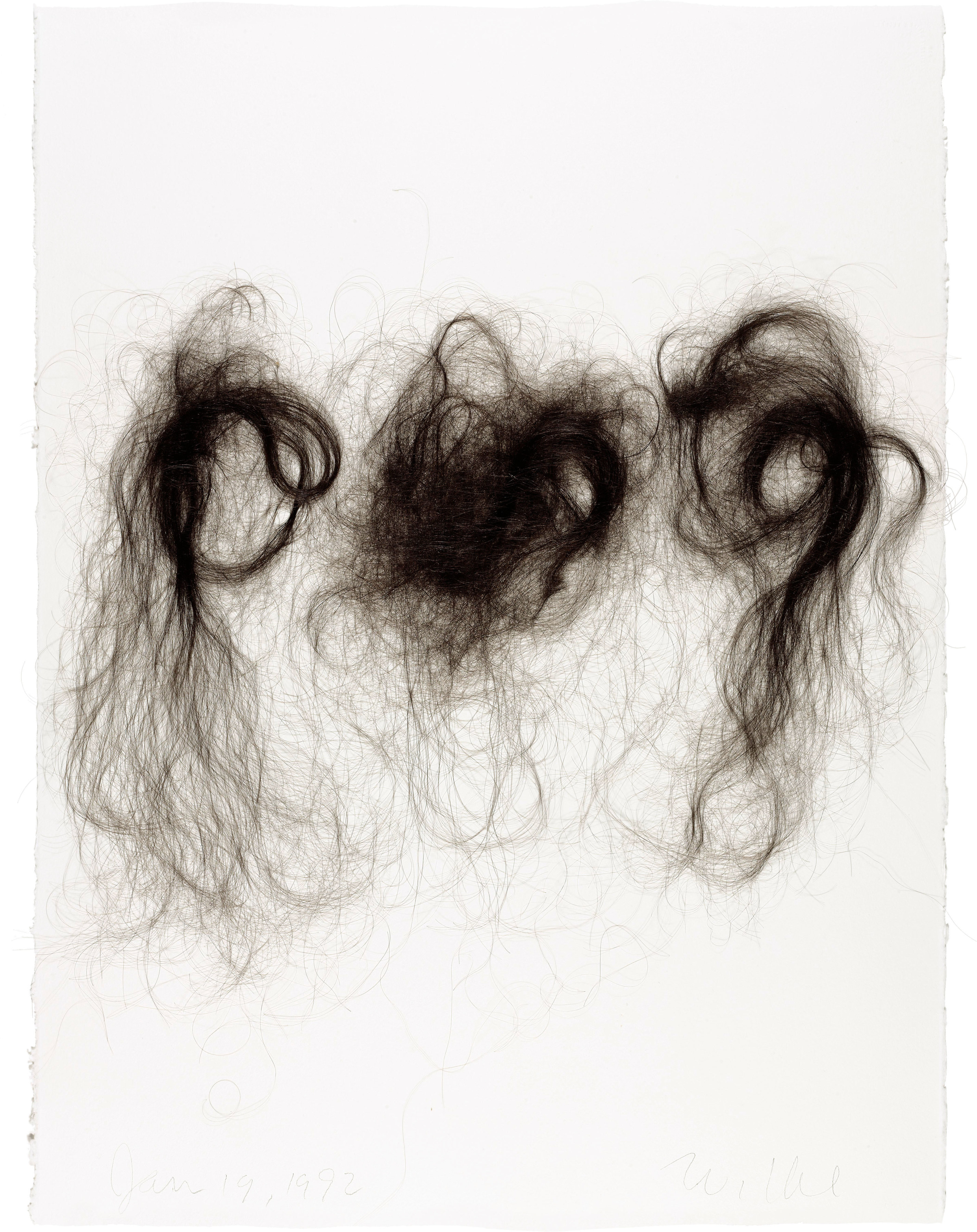

Hannah Wilke

Brushstrokes: January 19, 1992, no. 6, 1992

Artist’s hair on paper

30 × 22 1/4 inches (76.2 × 56.5 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon & Andrew Scharlatt, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

Eva Hesse peering through her sculpture of

rubber-dipped string and rope in 1969,

photo by Henry Groskinsky

Photo: Getty Images / The LIFE Picture Collection.

Eva Hesse

Test piece, 1967-69

Latex, wax

2 × 3 1/2 × 4 inches (5 × 9 × 10 cm)

University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and

Pacific Film Archive; Gift of Mrs. Helen Charash.

Image courtesy The Estate of Eva Hesse.

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

1967–70

When Hesse first uses latex, she begins by molding it, creating a series of small works or tests. These works are comparable to Wilke’s vulvic sculptures and suggest that Hesse’s first experiments with latex comprise basic interventions into the material.

Subsequently, Hesse begins to approach the material differently, building the latex up in layers. In a diary entry from September she describes the process of making the floor-based sculpture Schema and its related test pieces:

Am in the process of casting a sheet of rubber (on Sol’s table) 3’6”. On top of which sit semi-spheres 2 1/8” in diameter. It is all transparent to translucent, clear rubber. Looks like that vinyl type hose. It’s a long process, painted on with brush and having to wait ½ hr. to one hr. between coats. Although this varies depending on size of what I cast, thickness etc. The sheet will need 10 coats.23

Eva Hesse in her Bowery studio, 1969

Image courtesy The Estate of Eva Hesse.

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

In March 1968 Dorothy Beskind finishes a film of Hesse working in her studio, capturing Hesse’s process and use of latex. At the same time, Beskind documents Hesse’s use of a gridded table given to her by Sol LeWitt, which provides a worktable for staging her test pieces. The film evidences the multiple materials, methods, and processes that Hesse works with simultaneously.

Later in 1968, Hesse begins working with fiberglass and polyester resin guided by the expertise of Doug Johns from Aegis Reinforced Plastics on Staten Island. This experimentation results in a number of test pieces, or what Briony Fer has named the “studioworks.”24 These objects show Hesse’s thinking through materials and provide keys to the sculptures. Hesse gathers some of the test pieces together and displays them in glass cases as finished sculptures, attesting to the importance of these works.

Interested in the translucent quality of fiberglass, she experiments with the material further after Repetition Nineteen III and completes Accretion, which comprises fifty tall tubes that lean against the wall.

On November 16, 1968, Hesse’s first solo exhibition of sculptures opens at the Fischbach Gallery. The exhibition is titled Eva Hesse: Chain Polymers, evidencing the significance of her use of plastics. Hesse shows Schema, Sequel, Repetition Nineteen III, Accretion, Sans II, Accession III, and Stratum, as well as drawings and test pieces. She writes of the exhibition:

I would like the work to be non-work. This means it would find its way beyond my preconceptions.

What I want of my art I can eventually find. The work must go beyond this.

It is my main concern to go beyond what I know and what I can know.

The formal principles are understandable and understood.

It is the unknown quality from which and where I want to go.

As a thing, an object, it acceded to its non-logical self.

It is something, it is nothing.

Installation view of Eva Hesse: Chain Polymers at Fischbach Gallery, New York, 1968

Image courtesy The Estate of Eva Hesse. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Eva Hesse

Right After, 1969

Fiberglass

5 × 18 × 4 feet (152.4 × 548.6 × 121.9 cm)

Milwaukee Art Museum; gift of Friends of Art (M1970.27).

Image courtesy The Estate of Eva Hesse.

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Hannah Wilke

It Was a Lovely Day, 1964

Unglazed terracotta

3 1/4 × 3 1/4 × 4 1/2 inches (8.3 × 8.3 × 11.4 cm)

Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art, The Wichita State University

© Donald Goddard. Courtesy Donald and Helen Goddard and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York.

Hesse is also invited to show Sans II in the Whitney’s 1968 Annual Exhibition: Contemporary American Sculpture. The museum later purchases part of Sans II.

The importance of Hesse’s experiments with new materials is marked by the many exhibitions organized around that theme, including Made in Plastics in 1968 at the Flint Institute of Arts, where she exhibits Repetition Nineteen III alongside work by Donald Judd, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Morris, Louise Nevelson, and Claes Oldenburg; and A Plastic Presence at the Jewish Museum in 1969, where she shows Right After, which hangs from the ceiling. The sculpture’s translucent fiberglass- and polyester resin coated-wires make up looping forms that appear to be made of nothing at all. Her work is also included in an exhibition at the Owens-Corning Fiberglass Center in April 1970.

Hesse’s use of materials marks her distance and difference from Minimalism. Her interest in the imperfections produced by her materials and processes, and the impossibility of perfect repetition, give form to a new sensibility. Her sculptures are included in a series of era-defining group exhibitions including Eccentric

Abstraction; Anti-Form at John Gibson Gallery in October 1968; 9 at Leo Castelli in December 1968, curated by Robert Morris; When Attitudes Become Form, curated by Harald Szeemann at the Kunsthalle Bern in March 1969; and Anti-Illusion: Procedures / Materials curated by Marcia Tucker and James Monte at the Whitney Museum of American Art in May 1969.

Despite Hesse’s interest in these newer materials, her use of more mundane things is also recognized and brings her into relation with the material experiments of the historic avant-garde. In 1970, Ennead is exhibited at the Sidney Janis Gallery in String & Rope, alongside works by Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Bruce Nauman, Pablo Picasso, Robert Rauschenberg, Lucas Samaras, Kurt Schwitters, and others.

1960–79

Wilke’s experiments with the effects of different and new materials for her sculpture begin while she is still in art school. Although she works with ceramics, “creating layered vaginal forms in natural browns and terracotta,” for most of the 1960s, she looks to plastics as early as 1960.26

I started making fiberglass pieces in my senior year in college because its plasticity allowed me to create curvilinear and architectonic form simul-taneously... I painted them black in the tradition of metal sculpture... Those sculptures were abstracted arm- and leg-like structures reaching up with big separate centers connecting them, and they were definitely vaginal. I named them with erotic titles (Embouchure, Nymphae, Candida, Oncos...) I was aware by the time I was twenty that they were vaginas and we talked about it in college at the time.27

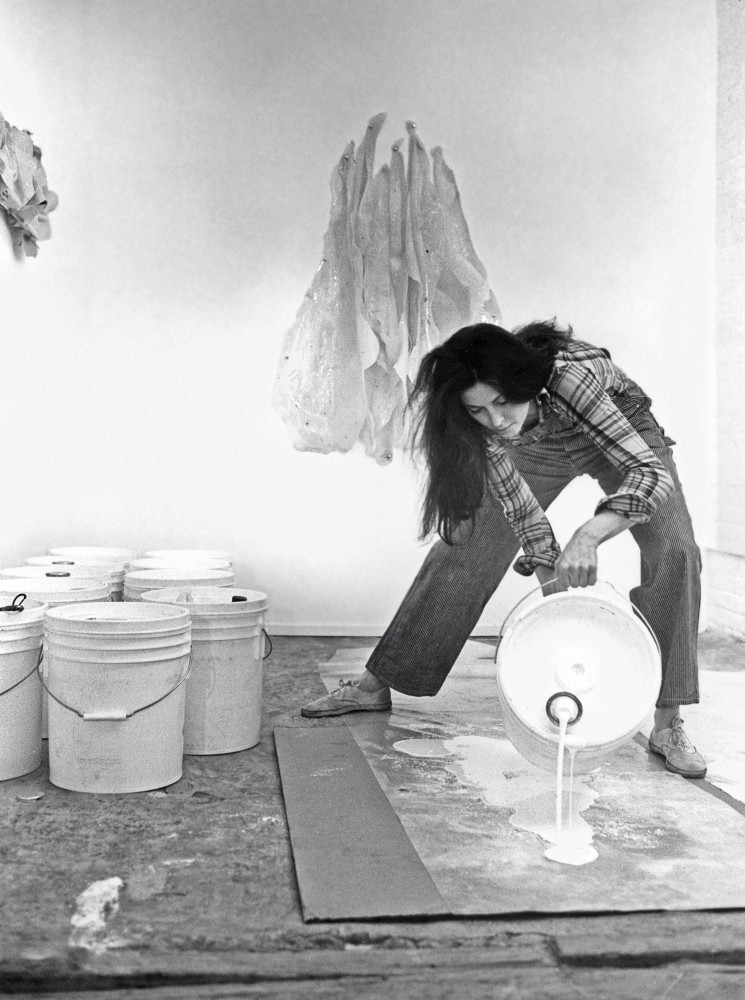

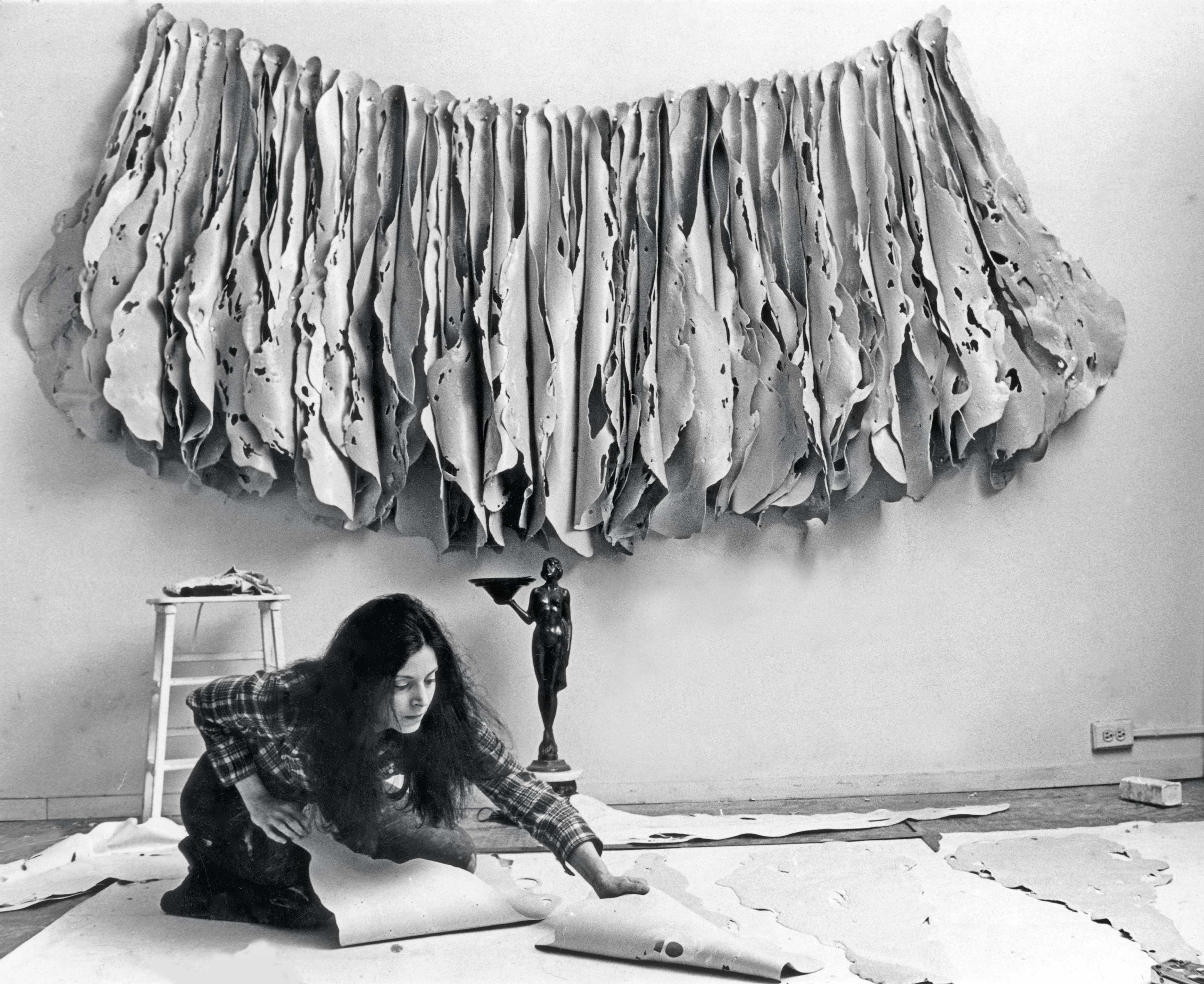

Hannah Wilke pouring latex in her Broome Street studio,

New York, 1974

Image: Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles

In 1970 she begins to use latex to make a series of wall-based works that mark a departure from her vulvic sculptures. To make these works she pours liquid latex onto plaster in strips and in circles, which are peeled off when dry. The dried latex shapes are then connected with metal snaps and hung on the wall with pins. She comments, “When I developed my latex hangings, I decided to use metal snaps to hold the folds together, but also to combine toughness and softness... I like the shiny, gritty nastiness and the fact that the snaps make the structure possible—as well as vulnerable. You want to unsnap the piece, but that would destroy the shape.” 28 Examples of these early works were shown in exhibitions at the Newark Art Museum, Newark, New Jersey, and Kunsthaus (Gedok), Hamburg, Germany in 1972. Her latex wall hanging In Memory of My Feelings, an homage to the poet Frank O’Hara who died suddenly in an accident in 1966, is included in the 1973 Whitney Biennial.

In 1971 Wilke begins experimenting with other materials in her sculptures, including lint. She exhibits Laundry Lint (C.O.’s), made between 1971 and 1973, at her Ronald Feldman Fine Arts exhibition exhibition in 1974. Unlike Wilke’s work in ceramic and latex, the lint works have a direct body correlative, in that they combine detritus from the laundry process including fibers and clothing, as well as hair and skin.

The “C.O.” in the title of this work stands for Wilke’s partner at the time, the artist Claes Oldenburg with whom she is in a relationship for eight years.

Hannah Wilke

Venus Cushion, 1972

Latex and snaps

63 × 32 inches (160 × 81.3 cm) no longer extant

Image: Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles

In 1973 Wilke makes Centerfold, commenting in Viva magazine that “it expresses a metaphysical feeling related to orgasmic ecstasy.”29 Despite the title’s allusion to the pornographic magazine, it is also a description of the sculpture, which is composed of latex hung from a single point so that it seems to fold in on itself. Wilke’s explicit connection of this work to the orgasmic underscores the possibilities that material experi-ments in abstract sculpture present for a new kind of erotic art. One that also assuages binary gender.

In 1975 Wilke makes the latex sculpture installations Ponder-r-rosa series, the title is an early reference to Duchamp. Ponder-r-rosa 4, White Plains, Yellow Rocks, a group of 16 flower-like sculptures, is acquired by the Museum of Modern Art after her death. Like Ponder-r-rosa, Pink Champagne (1975) and Rosebud (1975) are different from the early hanging pieces—these accordion sculptures comprise compressed lateral gatherings of flesh-like folds, pierced with metal snaps.

At the same time as Wilke makes her fields of vulvic sculp-tures in ceramic and her latex wall-based works, she also begins using other, more mundane materials, first rubber erasers, then chewing gum, to create smaller versions of the same form.

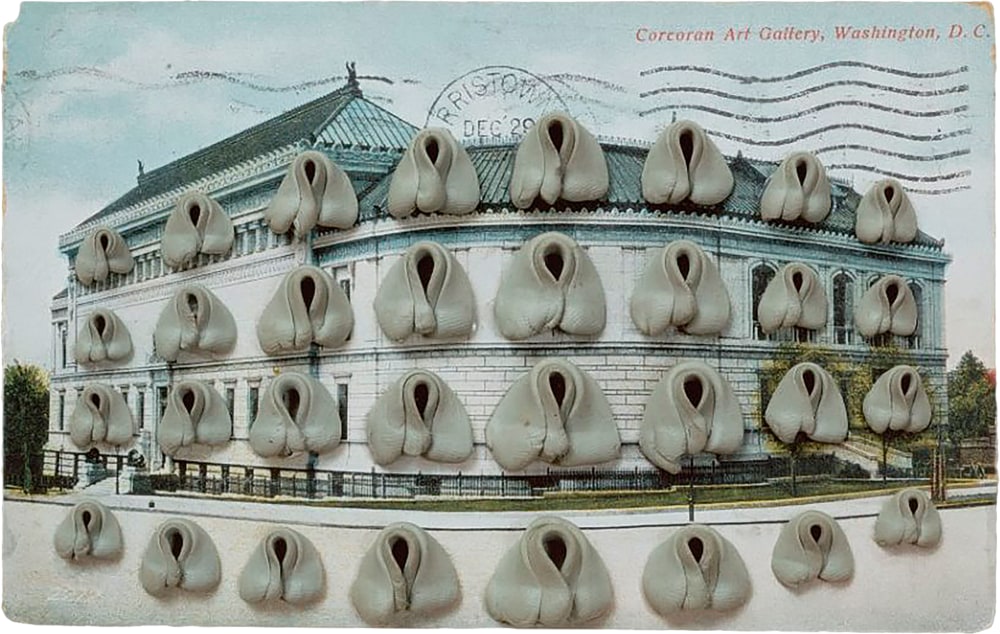

Like the large ceramic fields, Wilke makes these sculptures in series, attaching them to different backings from painted boards to postcards. In the postcard works shown on the wall, sometimes the forms correspond to the background image as if the sculptures occupy or take over the scene, as in Corcoran Art Gallery (1976); at other times they extend beyond the postcard, but take their organization from the base image, whether that be the geometry of an Atlantic City square, as in Atlantic City Boardwalk (1975), or the irregularity of rocks in a creek as in Catskill Creek (c. mid-1970s).

![Hannah Wilke

Laundry Lint [C.O.’s], 1971–73

Double fold lint, dimensions variable

Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

Courtesy Alison Jacques, London.](https://img.artlogic.net/w_1000,h_1000,c_limit/exhibit-e/605b3ed32390d8586573c7a2/c2f145b0f5f97e6c5aba8c23680d7345.jpeg)

Hannah Wilke

Laundry Lint [C.O.’s], 1971–73

Double fold lint, dimensions variable

Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

Courtesy Alison Jacques, London.

The use of chewing gum as material is meaningful. The bodily associations of gum through the process of chewing offers an intimate and sensuous link to the body of the maker. The connection between the mouth and the vulvic subject matter also prompts erotic connotations; these works are also included as part of a work Wilke produces for an exhibition of artists’ toys, called S.O.S. Starification Object Series: An Adult Game of Mastication (1974–75). The proposed game involves players chewing gum to make sculptures to place on the artist like those in the black and white photographs included in the game.

Hannah Wilke

Hannah Wilke in her Broome Street studio with Centerfold on wall, 1973 (no longer extant)

Image: Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles

Wilke makes the game for the exhibition Artists Make Toys at the Clocktower Gallery in New York which is supposed to lead to a series of multiples and Wilke exploits the potential of a money-making edition by stipulating that each game requires the artist to be present for a fee. As she is adorned with gum sculptures, Wilke becomes “starified”—a punning play on her becoming a celebrity, and therefore a rich artist, and the scarification that the gum sculptures looked like on her body—the cost of renown. The game is never made into a multiple, but Wilke continues to explore starification in her series of S.O.S. photographic performance works.

Hannah Wilke

Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, D.C., 1976

Kneaded erasers on postcard mounted on board

15 3/4 × 17 3/4 inches (40 × 45.1 cm)

Collection of Tony and Gail Ganz

Image courtesy Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

Wilke’s use of erasers is also significant. To work with this material, Wilke kneads the rubber into a pliable form. Once made, the small sculptures are arranged on boards in grids or irregular organizations, creating smaller versions of the larger ceramic fields, which are also shown laterally, rather than on the wall. These have the homophonic title Needed-Erase-Her, underlining a connection between the material of the sculpture, the eraser, and the gendered— “her”—content, as well as her contention that women are “erased.”

The title also speaks to gendered stereotypes, neediness, and plays out the Lacanian association of woman with lack, as in the erase[d] her, with proliferating vulvic forms. Wilke’s use of the grid and her monochromatic presentation resonates with some of Hesse’s grid sculptures and certainly her works on paper, which similarly juxtapose measured regularity with series of irregular forms.

Eva Hesse

Addendum, 1967

Papier-mâché, wood, and cord

84 5/8 × 119 1/4 × 8 1/4 inches (215 × 303 × 21 cm)

Tate, Purchased 1979

Image courtesy The Estate of Eva Hesse.

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Hannah Wilke

S.O.S. Starification Object Series (Curlers), 1974

Gelatin silver print | 40 × 27 inches (101.6 × 68.6 cm)

Performalist Self-Portrait with Les Wollam

Whitney Museum of American Art; Purchase with funds

from the Photography Committee and partial gift of

Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt.

Lippard argues that Hesse’s use of the serial form in conjunction with the grid and other geometries is important to understanding her work. She writes, “the system was only an armature; her geometry was always subject to curious alterations, her repetitions to a tinge of fanaticism.”30 Hesse herself comments, “Series, serial, serial art, is another way of repeating absurdity.” 31

Absurdity is a means for Hesse and for Wilke to step beyond the known and the accepted, and to take risks. Hesse seeks to reach absurdity through formal means, but like Wilke, also uses her titles to make a point. Sometimes Hesse’s titles are fabricated words, sometimes found phrases and sometimes synonyms for titles of other works. She is certainly aware of the effect of her titles in mystifying the associations that her objects might provoke. Her close friends Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner recognize this too, and in 1966 Bochner gifts Hesse a thesaurus to progress her wordplay. Even if Rosalind Krauss sees Hesse’s work as “a retreat from language” and “a withdrawal into those extremely personal reaches of experience which are beyond, or beneath speech,” Hesse uses language as another material.32

Wilke’s use of language is punning, but less playful than Hesse’s. Wilke is aware of the gendering of language and uses her titles to do double and sometimes triple service, invoking the salacious and the salubrious simultaneously.

[BANNER, LEFT] Photo of Eva Hesse in her studio, 1968, by Fred W. McDarrah / Getty Images. [BANNER, RIGHT] Photo of Hannah Wilke in her Broome Street studio, 1973. Image courtesy Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

23

Lippard, Eva Hesse, p. 112.

24

Briony Fer, Eva Hesse: Studio Work (London and Edinburgh: Yale University Press and Fruitmarket Gallery, 2009).

25

Lippard, p. 131.

26

Finberg, p. 16.

27

Ruth Iskin, “Hannah Wilke: In Conversation with Ruth Iskin,” Visual Dialog 2, no. 4 (1978), p. 17.

28

Hannah Wilke, “Hannah Wilke: A Very Female Thing,” New York Magazine, (February 11, 1974), p. 58.

29

Linda Crawford, “Women in the Erotic Arts,” Viva (January 1974), p. 82.

30

Lucy R. Lippard, “Eva Hesse: The Circle,” From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art, ed. Lucy R. Lippard (New York: EP Dutton, 1976), p. 159.

31

Elizabeth Sussman, ed., Eva Hesse (New Haven and San Francisco: Yale University Press and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2002), p. 27.

32

Wagner, p. 199.