This blog is a new project, intended as a space where unformed thoughts might find their first articulation. Over the 2014 Fall semester I am going to attempt to record a daily thought: just something small that is interesting or troubling me. I welcome your feedback, and hopefully some of these posts can spark further thoughts, debate or critical exchange.

—

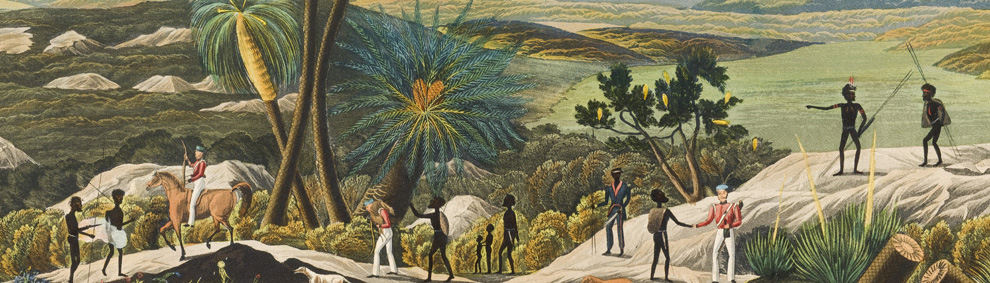

Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui installation image at the Brooklyn Museum (photo by author).

In recent months, my thoughts have increasingly turned to the use of found materials in the work of Indigenous artists. In part, these investigations have been motivated by an attempt to think through the nature of objecthood in Aboriginal art. Although not strictly an “Indigenous artist,” one artist that I have been testing some of these ideas against is the Ghanian born sculptor El Anatsui. I have found it extremely difficult to articulate why I find Anatsui’s work so compelling. When you describe his work – “he uses old liquor bottle tops and turns them into flowing tapestry like sculptures” – they sound a bit twee. But when you stand before these works, it is impossible not to be moved by their poetry and grace. On the one hand, Anatsui is a master of teasing out the former associations of his recycled materials. Here is the description of a 1998 work titled Motley Crowd:

For Motley Crowd … Anatsui used house posts he took from deserted homes in Nsukka region. Historically, when a house built in a vernacular style, primarily of earth and wood, became dilapidated the hardwood posts were reused to build a new house. Some posts supported generations of homes, making them ripe metaphors for endurance and connections to those who came before.

(Exhibition Label, from the exhibition Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui, Brooklyn Museum, February 8 – August 18).

It is clear that Anatsui is mining these kind of relationships across his oeuvre, but what happens after these materials are turned into works of art? Like most Aboriginal art, critical commentaries seem to fall a bit short here. Certainly, we can all see that Anatsui is making something of great beauty, but there is clearly something else at play here.

Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui installation image at the Brooklyn Museum (photo by author).

I was lucky enough to make it to the Brooklyn Museum to see the final weekend of the exhibition Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui. One thing that struck me in the exhibition, which is made up predominantly of recent works (2010-2011), is that Anatsui’s work is getting better and better. Compared to older works in the British Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art or MoMA, he seems to be finding subtle new ways to engage with his materiality. The end result is that the works seem much less forced, less bombastic and much more inventive. For me, these recent works are not just engaged a straightforward criticism of colonialism (the effects of alcohol, poverty, etc), but rather, are suggesting something radically new. In their delicate lightness, Anatsui’s recent works seem to be less about the material itself (bottle-caps), than they are about asserting their own individual presence. In other words, is it possible that these works are becoming less about transformation (turning bottle-caps into art; reframing African modernity in poetic terms), and more about the ineffable reality of presentness? These works leave behind any simplistic reading as “alternative modernities” for something that is much more assured in its transcendent contemporaneity. Since leaving the exhibition, Anatsui’s works have rarely been far from my mind. I wish I could have returned to the exhibition several times, because his works raise so many questions, which are almost impossible to ask when standing before their dazzling radiance.