On June 20, 2015, Miriam Schapiro passed away. Schapiro leaves behind a tremendous legacy in the art world, and on this occasion it seems fitting to explore one small part of it.

Schapiro produced several prints at Graphicstudio in 1983-1984. Four monoprints were essentially collages on paper. Children of Paradise was produced as an edition variée, an edition where each print contain more differences from each other than in a standard edition. In this case lithographic elements were used in the background and the collaged fabrics were different in each print. Kenny Scharf (Space Travel, 2002) and Christian Marclay (Sploosh (Handpainted), 2012 and Splat, 2013) would go on to produce notable editions variée for Graphicstudio.

Ruth E. Fine, curator for the National Gallery of Art, explored the creation of Children of Paradise in the catalogue for Graphicstudio: Contemporary Art from the Collaborative Workshop at the University of South Florida, an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC from September 15, 1991 to January 5, 1992. Her investigation follows.

“The collagists who came before me were men, who lived in cities, and often roamed the streets at night scavenging, collecting material, their junk, from urban spaces. My world, my mother’s and grandmother’s world, was a different one. The fabrics I used would be beautiful if sewed into clothes or draped against windows, made into pillows, or slipped over chairs. My ‘junk,’ my fabrics, allude to a particular universe, which I wish to make real, to represent.”

Miriam Schapiro, in Ruddick and Daniels 1977

Children of Paradise, 1983-1984. color lithograph and collage on Arches Cover paper (collage elements on Rives BFK “light-weight” paper). 31-7/8 x 48 inches. Edition: 60; 3 PP; 2 PrP; 1 GP; 1 USFP; 15 AP; 1 WP

In Children of Paradise Miriam Schapiro applied to the art of printmaking the collage principles she has called “femmage.”1 Schapiro has been creating femmages since the early 1970s, initially inspired by her use of found materials in her exploration of autobiographical and woman-centered themes for her contribution to Womanhouse, a feminist installation project at the California Institute of Arts.2 Combining scraps of fabric, lace, quilting, and other handwork with paint and, here, printer’s ink, Schapiro’s femmages intentionally recall traditional handwork techniques such as appliqué and quilting.3

In the forefront of the feminist movement, Schapiro invented femmage as a means of bringing together the disconnected public and private aspects of her life: “The change came when I applied fabric to canvas. I always felt my life had been separated, that I walked out on my intimate life, my domestic life, as a wife, a mother, a child of my parents, when I went to the studio. My real life was one thing, my art another.”4

Children of Paradise, 1983-1984. color lithograph and collage on Arches Cover paper (collage elements on Rives BFK “light-weight” paper). 31-7/8 x 48 inches. Edition: 60; 3 PP; 2 PrP; 1 GP; 1 USFP; 15 AP; 1 WP

Schapiro’s strength as a colorist is clearly revealed in her bold use of vibrant and competing hues in both Children of Paradise and its preliminary study Together. Two articles of children’s clothing, a girl’s dress and a boy’s suit, serve as the core elements around which Schapiro has built the composition. Layering color and texture in the form of hearts and teacups cut from fabrics and houses cut from patterned paper–all familiar in Schapiro’s repertoire of images–she creates a highly structured composition that nevertheless appears unstructured, reminiscent of the haphazard arrangements of some crazy quilts.5 The large, patterned bandanna in Together has been turned on end in Children of Paradise to form a diamond but serves the same unifying purpose in both compositions. The centered rectangle/square is a compositional device often used by Schapiro.6

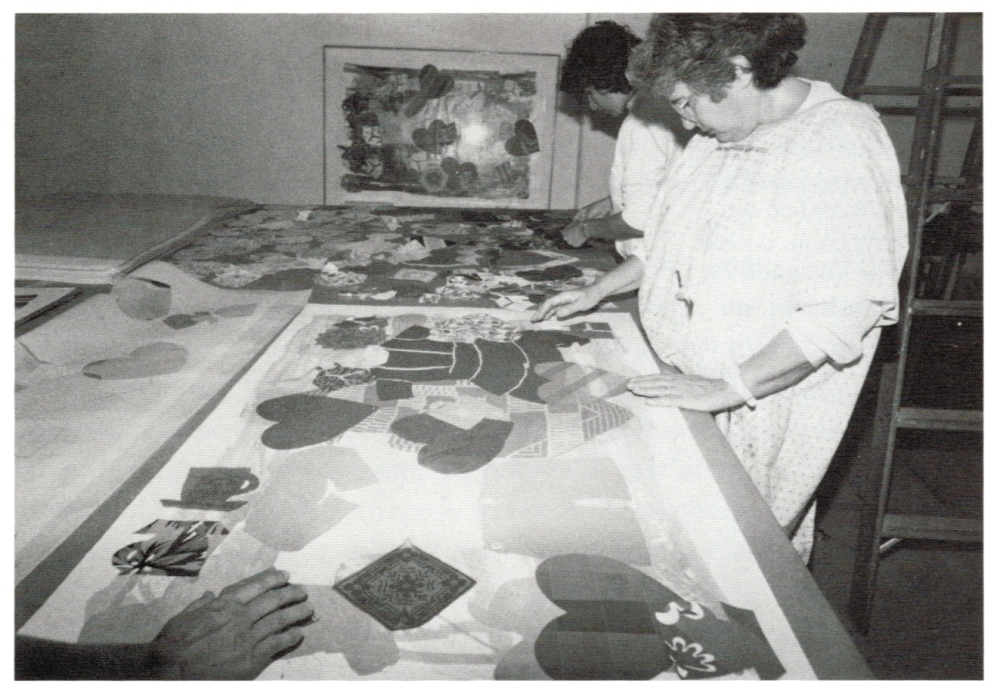

Miriam Schapiro (right), assisted by Liz Jordan, applies collage elements to Children of Paradise, 1984

Schapiro worked from fabrics she brought with her to the Graphicstudio workshop–“pieces from woman’s culture”7–as well as material she collected in Tampa, to create about a dozen preliminary femmages before executing the edition print. In the print Schapiro’s layering of transparent inks with fabrics, possibly suggesting “levels of the past,”8 locks the cutout shapes into a compositional whole. The fabric heart in the bottom left corner, for example, is echoed in the background lithography, connecting the layers of the image.

Baby Blocks, 1983. collage on paper. 29-7/8 x 30 inches

Julio Juristo printed Children of Paradise for Graphicstudio at Topaz Editions. The background of the print was printed from three plates hand-drawn by Schapiro in tusche and crayons. Approximately sixteen collage elements were added to each print. The clothing elements, along with the lace in the upper right corner, were created using photolithography, then razor-cut and drymounted to the lithographic background. A template ensured that the placement of the collage elements in each print was identical to the next.9 Yet the fabrics used in the edition vary greatly in color and pattern from print to print, making each print unique. Schapiro completed the collage work with the assistance of U.S.F. art students. As the artist recalls, “They worked on the 15 preliminary works and they bought fabric with me when I went on my fabric searches. We talked about their work, their plans. They were constantly involved in my process as enablers.”10

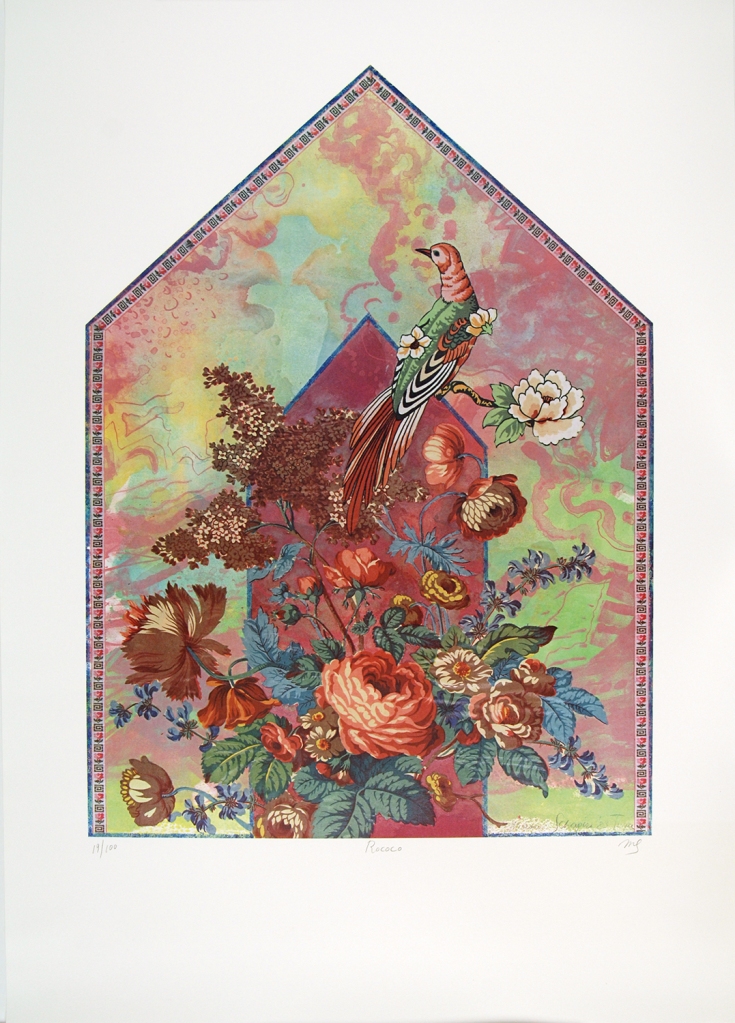

Rococo, 1984. offset lithograph produced in association with an exhibition at USF. 40 x 27-1/2 inches

Schapiro’s work is informed by a unique blend of modernism, autobiography, women’s history, and a feminist world view. In both Children of Paradise and Together the artist evokes the nurturing environment of people’s private lives–childhood, homes, capacity for love. In describing her world view, Schapiro has said: “The ‘intimate point of view,’ a woman’s point of view, begins in her kitchen. ‘What does a kitchen have to do with the people of Bangladesh?’ men will say. Well, but we say it has everything to do with it; the kitchen is where values are formed. The hearth is in the home. Nurturance means caring–caring for one’s family, for the poor, for the oppressed of the world.”11

Pandora’s Box, 1983. collage on paper. 31-1/2 x 48-1/4 inches

The cutout figures carry multiple associations, reminiscent of cutout cookies and paper dolls as well as the traditional techniques of appliqué practiced by generations of women. The heart and the house are recurring elements in Schapiro’s artistic vocabulary. The domestic associations of the house are but one layer of its importance. In fact, Schapiro has “come to see feminist art as a house, an ideological house, under whose roof each woman has her own individual room. She no longer has to be isolated; she can have community and she can work out her ideas collectively.”12 The heart, too, has multiple meanings:

The heart shape is often considered a woman’s shape. Candy boxes in the shape of hearts are frequently gifts from men to women. Heart shaped pillows are seen on women’s beds. Hearts masquerade as potholders, pin cushions and hooked rugs. Outside of their functional nature, what do these objects symbolize?

From the lexicon of quilt imagery, the hearts blend in with flowers, cups and houses, baskets, trees, stars and bars, squares and birds–all things domestic and rural.

Hearts stand for feelings.13

Together, 1983. collage with fabric, patterned paper (wallpaper/shelfpaper), and lithographed elements. 31-1/2 x 48-1/4 inches

In her description of Together, written in 1984 for a U.S.F. exhibition catalogue, Schapiro stated: “‘Femmage’ artist that I am, I have brought together ‘something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.’ In other words, I have allowed myself to be stirred by sentimental values in my effort to make my point about a sentient surface laden with memory and history. ‘Being’ is represented in the two clothing people, the little boy in his suit and the little girl by her dress. Here once again, the culture of women as differentiated from the culture at large has provided me with the role models for what I hope is a more universal statement about us as children, when we were very young.”14

Notes:

1. Schapiro and Melissa Meyer coined the term “femmages” to describe Schapiro’s approach to collage. See Schapiro 1985; originally published in Heresies, no. 4 (1978): “We feel that several criteria determine whether a work can be called a femmage. Not all of them appear in a single object. However the presence of at least half of them should allow the work to be appreciated as a femmage.

- It is a work by a woman.

- The activities of saving and collecting are important ingredients.

- Scraps are essential to the process and are recycled in the work.

- The theme has a woman-life context.

- The work has elements of covert imagery.

- The theme of the work addresses itself to an audience of intimates.

- It celebrates a private or public event.

- A diarist’s point of view is reflected in the work.

- There is drawing and/or handwriting sewn in the work.

- It contains silhouetted images which are fixed on other material.

- Recognizable images appear in narrative sequence.

- Abstract forms create a pattern.

- The work contains photographs or other printed matter.

- The work has a functional as well as an aesthetic life.”

2. The Womanhouse project involved the refurbishing of a house by Schapiro, Judy Chicago, and a group of twenty-one of their women students in the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts. Once repaired, the rooms of the house were designed not for habitation but as aesthetic constructions following feminist themes. See Schapiro 1987, 25-30.

3. An earlier print in which Schapiro combined femmage with printmaking techniques in Female Concerns (1976), executed at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

4. Schapiro, in Degener 1985.

5. Schapiro discusses the history of the quilt and its relationship to her art in her essay, “Geometry and Flowers,” in Robinson 1983, also describing the construction of her femmage compositions: “I attached fabrics to my painted surfaces. After painting a simple geometric structure, which served as a container for a burst of fabrics, I often glued sheer materials like printed chiffon over my acrylic scaffold. They appeared to flutter against the structure like a bird seeking freedom from the cage.”

6. See, for example, American Dreams (1977-1980); Wonderland (1983); and Invitation (1982), all reproduced in Schapiro, St. Louis 1985.

7. Schapiro, correspondence with Corlett, 1990.

8. The concept of “levels of the past” was set forth by Schapiro with regard to American Dreams, in Schapiro, St. Louis 1985.

9. Schapiro, correspondence with Corlett, 1990.

10. Schapiro, correspondence with Corlett, 1990.

11. Quoted in Paula Bradley and Ruth A. Appelhof, “Excerpts from Interviews with Miriam Schapiro,” in Gouma-Peterson 1980, 44.

12. Schapiro, quoted in Lyons 1977, 43.

13. From Schapiro’s description of the femmage, An Amethyst Remembrance (1982), published in Schapiro, St. Louis 1985.

14. Humanism, Tampa 1984, 19.

Thank you for sharing works of the outstanding artist Schapiro!