Ex-minister Tzipi Livni: ‘Netanyahu’s government is acting against Israel’s democratic nature’

The former chief of justice returns to the public arena to accuse the executive of trying to ‘control the entire judicial system to promote an ideology that is against equal rights’

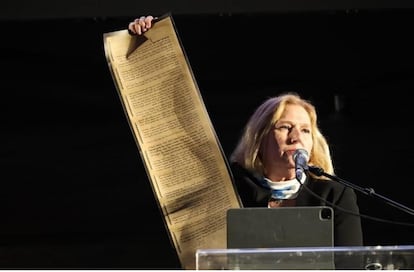

Tzipi Livni is back in the limelight. “On the public stage,” she clarifies, “not the political stage,” from which she retired four years ago. Last January, she was on her way to a rock concert when she heard Israel’s Justice Minister Yariv Levin present the now infamous judicial reform, which seeks to weaken checks and balances on the executive branch. She, a lawyer by training who twice held the same portfolio (the last time, under Benjamin Netanyahu), was alarmed. “I was shocked. I saw something like this coming, but not quite this,” she recalls from her home in Tel Aviv.

Since then, she has taken the floor in weekly demonstrations against the reform, increased her appearances on television and written opinion columns in newspapers. Technically, she has done so as an ordinary citizen, but everyone knows that she was the most powerful woman in Israeli politics since the legendary Prime Minister Golda Meir (1969-1974). She has been deputy prime minister, foreign minister and head of the last two negotiating teams with the Palestinians. She now worries that the focus on legal reform will divert attention from other measures of the executive formed by Netanyahu’s Likud with the ultra-nationalist and ultra-Orthodox parties, the most right-wing in the country’s 75-year history. “It is acting against the nature of Israel as a democracy,” she says.

Livni uses an analogy about driving to illustrate the judicial reform, which the public and diplomatic protests managed to paralyze last March, and which is now being negotiated between the government and the opposition. Electoral victories, such as the one won last December by Likud and its allies, are, she says, like getting a driver’s license. They confer the right to “take the country according to the direction that you believe is the best,” but “not to destroy all the road signs” nor to “break the speed limits.”

The Netanyahu executive, on the other hand, “has decided: no police, no gatekeepers in the government, no judges. No traffic signs.” “They want to control the entire judicial system to promote an ideology which is against equal rights, against democracy in substance. When talking about democracy, they say: ‘The majority rules.’ And I answer: ‘Yes, the majority rules, but it needs to preserve minority rights and human and civil rights,’” she argues.

Livni rarely smiles and speaks like many Israelis: plainly and bluntly. But she does not want to allude to the opposition leaders who are negotiating a consensual judicial reform under the auspices of President Isaac Herzog. They are, at the moment, her fellow travelers and eventual allies if she returns to politics. Her words show, however, that she is closer to the protesters and to the opposition that distrusts dialogue. “Every day there is another step that is changing Israeli democracy. And we cannot turn a blind eye to that while negotiating,” she points out before stressing that the opposition should not sit at the negotiating table as a lesser evil, a sort of alternative to the unilateral legislative roller coaster. “We have won this battle. Netanyahu knows he cannot move forward with brute force,” especially because “he really cares about his position in the international community.” He remains uninvited to the White House, and Likud is no longer the leading political force in the polls, she points out.

In one corner of the room, a shelf with books by Zeev Jabotinsky reveals her pedigree as a revisionist, the wing of Zionism represented by Likud. “Almost all of them were my parents’ books,” she says. They were members of the Irgun, the Zionist militia founded by Jabotinsky, which defended the armed hard line against the British Protectorate and the Palestinians. They carried out attacks such as the one that killed 91 people in the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. They were married on May 15, 1948, the day after the Jewish state was born and the first Arab-Israeli war began.

So, when she criticizes Netanyahu, it is not just because of her political and family background. He is also the person who offered her her first political post. After becoming a lieutenant in the Army, a few enigmatic years in the Mossad and a decade of work as a lawyer, she came within a whisker of the Likud seat in the first election Netanyahu won, in 1996. And the latter reinstated her to oversee the privatization program.

Ariel Sharon later became her political mentor. She followed him in 2005, when he split from Likud to form the Kadima party, with the aim of pushing forward legislation on the withdrawal of soldiers and settlers from Gaza. Three years later, as foreign minister, she was in charge of defending Operation Cast Lead to the world. In the offensive on the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip, more than 1,400 Palestinians, mostly civilians, were killed. “When Hamas gets stronger, the moderates get weaker. That was our strategy, and that’s why we negotiated peace and, when necessary, fought terrorism,” she asserts.

A year later, at the height of her popularity, she led Kadima to victory in the elections, but refused to give in to the demands of the ultra-Orthodox parties and fell just short of becoming the second woman to govern Israel. Some thought it showed integrity; others thought it was a huge tactical mistake. Netanyahu, in any case, took advantage of the opportunity, agreed on a coalition and has now been in power, almost without interruption, for 14 years. After the last elections, Livni believes, Netanyahu “gave a blank check” to his coalition partners “out of weakness.” “They wrote all the crazy ideas [in the government agreement] and he’s not even trying to moderate them,” she adds.

The former advocate of an Israel occupying the entire biblical territory has long since become, ideologically, one of the leading advocates of the creation of a Palestinian state. Her perspective is one-sided (“I speak of my interest as an Israeli, not of the Palestinians”) and pragmatic (“the goal is to preserve Israel as a Jewish and democratic state”). In fact, she led the last two peace negotiations with the Palestinians: a more serious one in 2007-2008, with Ehud Olmert as prime minister, and a more acrimonious one forced by Barack Obama between 2013 and 2014, with Netanyahu. Livni claims that she agreed to join the government of her then political rival because he handed her the negotiating baton. “Now he’s doing something completely different. He is not even willing to talk about it [a peace dialogue],” she laments after blaming Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas for the failure of the negotiations.

That was when her star began to fade, partly because of the political lurches, partly because of moving in an ideological direction to that of her country, and partly because of the rise of other candidates who appealed to her former voters. Her party, Hatnua, combined forces on the electoral list with Labour. In 2019, on the eve of a predicted electoral thrashing, and on the verge of tears, she announced that she was leaving politics.

Even so, she has not thrown in the towel on the so-called “two-state solution,” advocated by the international community to resolve the Middle East conflict. This is despite voices that consider that the demographics and decades of expansion of Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem and the West Bank prevent the creation of a Palestinian state at this point. “I hope it’s not too late. And if we get to a point where it is too late, we’ll need to think about what we do,” she says.

Once again, she uses a driving analogy. Her “national Waze” (the GPS navigation app) is driving towards “maintaining Israel as a Jewish and democratic state,” with a stop “at the peace station to hopefully find a path there.” “If I arrive and there is no one there [...] I will not change my destination to Greater Israel or anything that is not a democracy. And I will not put obstacles in my way: I will not expand settlements or build new ones. Because it’s a roadblock in the future, so why do it?”

“My destination is not two states for two peoples. My destination is a Jewish democratic state, and two states for two peoples is along the way. I hope it is still valid. But what I ask those who tell me that maybe it’s too late and that we have passed the point of no return is: ‘OK, let’s think together about the other solution. Because I don’t see it. We can think of something different, as long as we don’t have something on the table that is not a democracy, or a Jewish state, or that is apartheid,” she explains.

Livni believes that her country needs to preserve a Jewish demographic majority so that it will not one day have to choose between being Jewish-only or democratic-only. And that inexorably involves “separating from the Palestinians as soon as possible.” “We cannot annex millions of Palestinians and, if we do, we have to give them equal rights. And I am completely against any solution that would make us unequal or undemocratic,” she says.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition