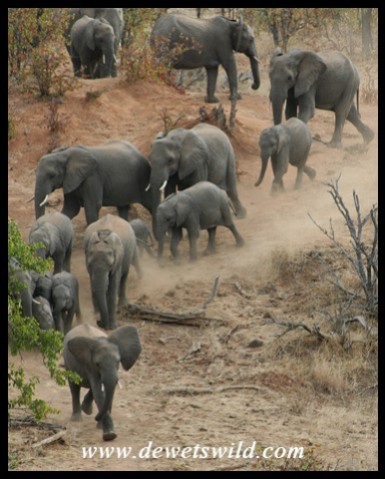

Elephants are a big drawcard for visitors to our parks and reserves, being charismatic animals and members of the famed “Big 5”. For us too, encountering elephants is always a special treat: witnessing the interactions between different herd members or the playful antics of the calves, and there’s few things in nature as beautiful as the gait of a confident elephant bull, his massive head swaying from side to side, intent on ensuring anything and everything in his way clears out before he gets there.

The 12th of August annually is celebrated as World Elephant Day. Elephants in Africa and Asia are faced with the threats of escalating poaching, habitat loss and various other conflicts with humans. With an estimated 100 African elephants killed daily for the illegal ivory trade in Asian markets, their population is in rapid decline. World Elephant Day was launched in 2012, to bring attention to the plight of these iconic animals, and has been observed annually since. South Africa has a growing population of almost 27,000 elephants (2015 estimate), but we have not been entirely isolated from the poaching happening on a larger scale in several other African countries.

One of our greatest joys when visiting South Africa’s wild places is being treated to an encounter with a real “Tusker”; a majestic elephant bull carrying massive ivory. There are only a handful of these enigmatic animals on the continent, and they are living monuments to those who protect our wild places for generations to come. Owing to their special status, they are given names by the Park authorities, often according to specific areas they roam or characteristic physical features or in remembrance of rangers or other members of staff that dedicated their lives to the Park.

Allow us to celebrate these magnificent creatures on World Elephant Day by sharing some of our encounters with Tuskers from four of our Parks with you.

Addo Elephant Park

With the proclamation of the Addo Elephant National Park in 1931, only 11 African Elephants remained in the Addo district. Addo’s elephants have responded wonderfully to the protection they’ve been afforded since the Park’s proclamation, and today number over 600! The population had an interesting trait however, due to hunting and the small founder population, in that the bulls had only small tusks and the cows had none at all. In order to address this, Park management translocated eight mature bulls from the Kruger National Park to introduce new genes into the pool in 2002 and 2003.

Valli was one of the bulls that moved to Addo from Kruger. He was named after then Minister of Environment and Tourism, Mohammed Valli Moosa. We saw Valli in bad light one afternoon in May 2010 while visiting Addo. Not a great photo, but a memorable experience! Sadly, Valli died in December 2017 following a fight with a younger bull.

Addo’s Valli seen in May 2010

We were most pleased to have this encounter with the beautiful Derek – certainly a contender for the vacant throne of Addo’s elephant king – during our December 2017 visit to Addo.

Unfortunately we weren’t around yet when Addo’s most famous elephant, Hapoor, ruled the Park for 24 years from 1944 to 1968. Today, a reconstruction of his head with the characteristic nicked ear that earned him his name has pride of place in the information centre at Addo’s Main Camp.

Pilanesberg National Park

There’s a population of approximately 240 elephants in the Pilanesberg National Park. Most of the fully grown adults in the Park today were babies when they were brought to the Pilanesberg from the Kruger National Park in the 1980’s , as the local population was eradicated by hunters before the Pilanesberg was proclaimed a reserve.

Pilane was one of six dominant bulls translocated to Pilanesberg from Kruger Park in March of 1998, when the absence of older bulls caused behavioural problems in the young bulls then transitioning to adulthood at Pilanesberg. At the time he was estimated to be about 34 years old and was named after Chief Pilane of the Bakgatla. We saw Pilane in March 2012. Unfortunately he has broken both his tusks in recent years and passed away in October 2020 from old age.

Mavuso is another of the Kruger Bulls transported to Pilanesberg in 1998. He is named after Mavuso Msimang, who was SANParks’ CEO at the time. We saw Mavuso on a visit to the Pilanesberg in November 2018 at which time he was estimated to be about 55 years old. Sadly, Mavuso was killed in a fight with a younger bull in August 2020.

Pilanesberg’s tusker Mavuso

Tembe Elephant Park

Tembe Elephant Park is home to over 250 elephants, the descendants of the last free roaming herds in this part of South Africa.

Isilo, meaning “The King”, was the biggest Tusker at Tembe Elephant Park and for a time also the biggest living Tusker in South Africa (after Duke of Kruger broke his tusks). It is believed that the gentle giant succumbed to natural causes, a dignified end befitting his royal stature, in January 2014. Sadly it was also made known that his enormous tusks have been stolen, presumably by rhino poachers who happened upon the carcass before rangers found it. We were fortunate to spend some time in Isilo’s majestic presence during our visit to Tembe in May 2013. You’re welcome to have a look at our special blogpost recounting our audience with Isilo.

When we visited Tembe Elephant Park in 2013 we were lucky to see several other impressive tuskers – Tembe is renowned for them! Even though Ucici, Lebo and Zero is no longer roaming Tembe’s sandy forests and marshland, there’s still a number of up-and-coming Tuskers flying the Park’s flag high as a hotspot for majestic elephants.

Kruger National Park

Our flagship National Park, the Kruger, and the surrounding reserves has a combined population of around 21,000 elephants, but only a handful of these can be considered true “Tuskers”. Kruger’s renown as a home of elephant bulls carrying impressive ivory started with the naming of the Magnificent Seven in 1980 – Shawu, Mafunyane, Ndlulamithi, Kambaku, Dzombo, Shingwedzi and Joao. These seven big bulls immediately captured the imagination of the public, both in South Africa and overseas. Today, the tusks of six of them (Joao’s tusks broke before his death), along with the tusks of a few other big bulls that came after them (notably Nhlangulene, Mandleve and Phelwana) may be marveled at in the Elephant Hall in Letaba Rest Camp.

Over the years we were blessed to see several impressive Tuskers in the Kruger Park. Here’s a few of them.

Hahlwa

We’ve had two encounters with the big bull known as “Hahlwa“, which is Tsonga for “twin” because he looks so similar to Masasana, another big Tusker roaming the Kruger Park (see further below). When we saw him the first time in June 2016, Hahlwa didn’t have a name yet, but this was corrected in May 2017 when the Kruger’s Emerging Tuskers Project announced him as one of the new crop of magnificent Tuskers to be seen in the Park. When we therefore saw him again in April 2018 we could put a name to the face. Unfortunately Hahlwa broke off most of his right tusk later in 2018.

Hlanganini

Hlanganini was named after a small stream that has its confluence with the Letaba River in his relatively small home range around Letaba Rest Camp. We were fortunate to see Hlanganini just a stone’s throw from Letaba one afternoon in September 2007. Hlanganini’s carcass was found in August 2009, with rangers speculating that he died as a result of a fight with another bull about two months earlier. Just a couple of months before his death Hlanganini broke his left tusk. The stump of his left tusk measured 2.04m and weighed 45kg, his right tusk was 2.7m long and weighed 55.8kg.

Kukura

Kukura was first noticed by the staff in the Kruger Park during 2015 and was given his name due to the speed at which his tusks are growing since then (the word Kukura being Shona for “growing”). We were lucky to see him drinking from a spruit on the 24th of December, 2021.

Machachule

Machachule means “the lead dancer” and was the nickname of late ranger Joe Manganye who served for 33 years in the Kruger National Park. Machachule originally had a large home range that stretched between the Letaba and Shingwedzi Rivers, but was later regularly seen only around Shingwedzi Rest Camp. With Shingwedzi being one of our favourite places in the Kruger National Park, we were treated to two sightings of Machachule; the first being in October 2008 and the next almost three years later in June 2011. Sadly there doesn’t seem to have been any sightings of Machachule in the last few years and it is possible that he has died somewhere in the wilderness.

Masasana

To date we’ve had two encounters with Masasana, one of the biggest Tuskers currently roaming the Kruger National Park. Our path crossed with his in June 2011 and then again in May 2018. Masasana shares his name, which means “one who makes a plan”, with retired Kruger staff member Johan Sithole who worked in the Park for 35 years.

Masbambela

Marilize and I saw Masbambela, at the time thought to be the second biggest Tusker in the Kruger Park, on the 15th of January 2006 along the S56 Mphongolo Road between Shingwedzi and Punda Maria Rest Camps. His usual home range was in the wilderness area west of Shingwedzi and he was seldom seen near the tourist roads. Masbambela was named after late ranger Ben Pretorius, who’s nickname means “one who can stand his man”. Some months after we saw Masbambela he broke the tip off his left tusk. Masbambela died of natural causes in November 2006. His tusks were recovered and the right measured 2.31m long with a weight of 49.05kg, while the remainder of his left tusk was 2.07m in length and weighed 42.75kg.

Mashangaan

Mashangaan was named after ranger Mike “Ma Xangane” English, who was fluent in the Shangaan language and worked in the Kruger Park for 33 years. This old Tusker, who had a limited home range around Letaba Rest Camp, was estimated to have been around 58 years old when he died in August 2011. His left tusk measured 2.48m in length and weighed 42.9kg, the right weighed 37.3kg and was 2.07m long. We had just one encounter with Mashangaan, in September 2007.

Masthulele

Masthulele, “the quiet one”, was named in honour of renowned scientist and elephant expert Dr. Ian Whyte, who served in the Kruger National Park for 37 years. Masthulele roamed a vast area between Giriyondo Gate (north of Letaba Rest Camp) and the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve west of Kruger, and we were lucky to have had six different encounters with him (September 2007, June 2011, April 2012, June 2013, September 2013 and April 2014), all close to Letaba, making him a familiar favourite for the Wild de Wets. At the time of his death of natural causes late in 2016, Masthulele was considered the biggest Tusker in the Kruger Park and South Africa. His left tusk weighed 51kg and the right 54kg, and they were 2.34m and 2.45m long respectively.

Muliliuane

This big Tusker was named after ranger Harry Kirkman who spent 36 years working in both the Kruger National Park and Sabi Sand Wildtuin (game reserve) until his retirement in 1969. Like Mr. Kirkman, Muliliuane’s home range included both these conservation areas. We saw Muliliuane only once, in June 2005, and unfortunately he didn’t want to give us a good view of his enormous ivory. Muliluane died at the end of 2007, in Sabi Sand.

Nambu

Nambu is becoming an ever more familiar sight for tourists and his tusks have grown impressively recently. We had a few encounters with Nambu during September 2019.

Ndlovane

Our first sighting of Ndlovane was way back in September 2005, when he was much less an imposing animal than later in life. We then saw him in July 2016 and again in May 2018. Although very impressive already, Ndlovane was still considered a young bull (Ndlovane means “small elephant”) and with age on his side Ndlovane could have grown to be one of Kruger’s biggest Tuskers. Ndlovane died of natural causes in October 2020, having been in poor condition for some months prior. It was determined post-mortem that a growth inside Ndlovane’s mouth severely hampered his chewing action, leading to him losing condition and dying. Ndlovane’s left tusk measured 257cm long and weighed 45kg while his right tusk was 267cm long and weighed almost 53kg.

Ngonyama

Ngonyama is a much larger Tusker today than when we saw him in February 2009 while enjoying a guided walk through the mopaneveld of northern Kruger. He was named after the late Dr. Uys de Villiers Pienaar, who started working in the Kruger National Park in 1955 and ended his career in 1991 as Chief Director of National Parks. “Ngonyama” is the isiZulu word for lion.

Ngunyupezi

Ngunyupezi, meaning “one who likes to dance”, was named after late ranger James Maluleke (33 years service). In April 2007, the de Wets were among the first people to lay eyes on this irritable bull with his uniquely shaped left tusk. He roamed a vast area from Pafuri to south of the Shingwedzi River, but was later seen mostly near Shingwedzi Rest Camp. Unfortunately there doesn’t seem to have been any recent sightings of Ngunyupezi and it is doubtful whether he is still alive.

Nkombo

Nkombo was named by research NGO Elephants Alive, who kept track of this emerging tusker with a satellite collar, which he lost in 2014. We were lucky to see him twice during a visit in September 2014. Sadly Nkombo’s carcass was found in September 2020. His right tusk broke shortly before his death and measured 197cm long, weighing in at 42kg. Nkombo’s left tusk weighed 46kg and was 233cm long.

N’wendlamuhari

We’ve had four encounters with the often irritable bull known as N’wendlamuhari, who’s name means “the river that is fierce when in flood”. Our first encounter with him was in 2009, and his tusks weren’t all that big then. It was therefore amazing to see him again in August 2011 and September 2012 and see how much his tusks have grown in stature. Today he is a very impressive specimen and we were fortunate to see N’wendlamuhari again on the 2nd of January 2020.

Xidudla

Xidudla is an impressive bull, the name being in reference to his large size. We were fortunate to cross paths with Xidudla twice in one day during a visit to Kruger in March 2018.

Xindzulundzulu

This bull’s Tsonga name means “walking around in circles” and is in reference to his very small home range centred around one of the Kruger National Park’s camps, where he is regularly seen. We were lucky to have seen Xindzulundzulu twice already – in September 2012 and December 2015 – and hope to see him at least a few more times still!

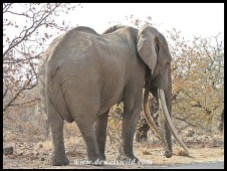

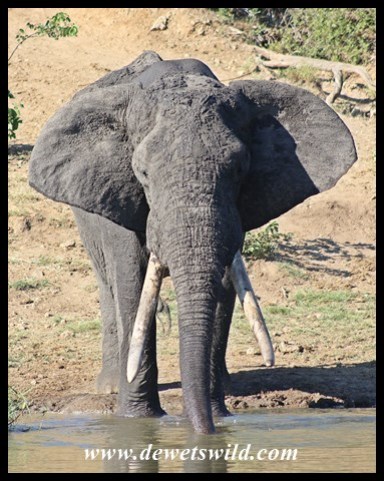

We’ve seen many more aspirant and impressive emerging Tuskers in Kruger over the years, many of which have not been named yet. These are a few of them.

Not wanting to attract the unwanted attention of poachers to these beautiful animals I’ve purposefully omitted the exact locations where we saw those Tuskers that are still alive. And if we are fortunate enough to see some of these big guys and others like them in future, we’ll come update this post with those pictures.