On Wednesday 13th July, the CREWS project hosted its first academic event, a seminar presented by Dr Christian Prager of the University of Bonn. The topic was “Of Codes and Kings: Digital Approaches in Classic Maya Epigraphic Studies”, and gave our speaker the opportunity to tell us all about the digital database of Mayan inscriptions that he is helping to build.

I have already said a little bit about the Mayan writing system in a previous blog post, Mayan Glyphs as a Writing System, which you may be interested in looking at for some thoughts on the script type. It was in use for a remarkably long period, between about 300 BC and 1500 AD, in parts of Central America. In terms of script classification, we can label Mayan as “logosyllabic”, meaning that it has signs for whole words (“logograms”) as well as signs for syllables (“syllabograms”) that can be used to spell words out syllable-by-syllable (like ka-ka-wa, the Mayan word for “chocolate”, which you may recognise as being close to the word cacao).

ka-ka-wa, “chocolate”

So why is a digital approach to Mayan important? Well, first and foremost, the digital database is a quest to record all we know about Mayan inscriptions, including pictures and 3D scans of the texts themselves as well as details of their location and what research has previously been done on them, and a wealth of information on the writing system, its signs and the words written in it. It will be a resource of immense value to anyone working on or interested in Mayan – and, even better, it will be freely accessible to all. You can already see some previews and access a lot of general information on the database’s website, linked to below:

TEXTENDATENBANK UND WÖRTERBUCH DES KLASSISCHEN MAYA

(Database and Dictionary of Classical Mayan Texts: the link takes you to the English version)

Dr Prager gave us a detailed introduction to the methods used by his project team to construct the database, and presented some of the problems in digitising this material. There is a great deal to say about this, and I will just pick up on one interesting aspect here today – but I recommend having a browse around the database website to get an idea of the scope of the project and to read some of the research that had already been published (including notes on a new inscription and the sign JALAM).

Dr Christian Prager, speaking on Mayan at the first CREWS event

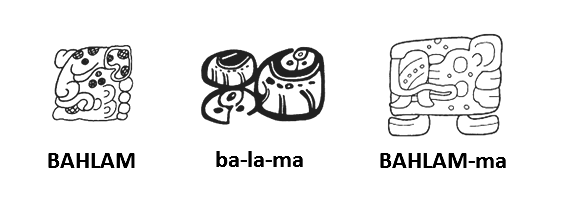

When creating a digital database, it is necessary to decide how to classify every item, from the inscriptions and their dates and locations right down to the level of individual Mayan signs written in them. One problem arises from the unusually high degree of variation of the Mayan writing system, both in the shapes of its signs and in the ways in which they were combined to form words. For example, there are different ways of writing the word for “jaguar”, bahlam, as you can see below: you can use a logogram alone (BAHLAM), spell it out syllable-by-syllable (ba-la-ma) or use a logogram with a phonetic complement to specify how the word ends (BAHLAM-ma; important for this particular word because it is confusable with another one meaning “ocelot”). (NB that Mayan syllabograms are ‘open’, which means that they always end in a vowel. So even if the word ends in a consonant, like bahlam, you still have to use a sign ma to represent the last sound, with the a in ma here functioning as a ‘dummy vowel’. Very similar spelling strategies can be found in the entirely unrelated ancient Aegean syllabic systems – see further the earlier post on Linear B, KO RE E WI SU.)

(NB that Mayan syllabograms are ‘open’, which means that they always end in a vowel. So even if the word ends in a consonant, like bahlam, you still have to use a sign ma to represent the last sound, with the a in ma here functioning as a ‘dummy vowel’. Very similar spelling strategies can be found in the entirely unrelated ancient Aegean syllabic systems – see further the earlier post on Linear B, KO RE E WI SU.)

If Mayan ways of writing whole words look complicated, you will not be reassured to hear that variation is not limited to the combination of signs to form words. There is also a great deal of variation in shapes of the individual signs that are combined to form the words. For example, the syllabic sign pa conventionally looks like a rounded shape that tends to have some cross-hatching in the middle, and this is the form that is usually combined with others. But it can also appear as a whole head, or even as a whole figure with a body (a “full-figure glyph”). Some variants for this sign are shown below.

Variants of the sign pa

You can imagine how complicated it might be to create and systematise a list of signs of the Mayan writing system when faced with such a high degree of variation. But, as Dr Prager explained to us, the database aims to achieve this by classifying not only each sign and but also its variants as well as each different way in which the individual signs can be combined with each other to form whole words.

Those of you reading who use an alphabet when you write may now feel rather lucky to have ended up with such an easy-to-use writing system, where each sign stands for a single sound, there is very little variation in the shape of each sign or in the ways you combine them in strings to make sounds. Modern alphabets are very efficient, and are fit-for-purpose in a highly literate society where you need writing in all sorts of aspects of your everyday lives.

The Mayan writing system, on the other hand, had a very different social context and served different purposes. In the questions following Dr Prager’s talk, it was striking that many listeners asked about the context of Mayan writing. How could the authors of these inscriptions cope with the degree of variation? Was the variation deliberate? Who might be able to read the inscriptions? How restricted was Mayan literacy?

The answer, of course, is that Mayan literacy must have been very restricted. The authors of inscriptions were not only committing words to writing but were creating an interactive visual monument, often prominently placed on a building or an object. So writing was, in a sense, also artistic and creative. While it is likely that not many people other than the authors of the inscriptions could read them, this did not mean that illiterate individuals were unable to interact with the inscriptions – a fact made obvious by their placement on buildings such as pyramids, for example, where they could be positioned on the steps and inner and outer walls, where people would walk on or past them.

Mayan glyphs incorporated into architecture at Copán

Context is all-important here, because the restricted nature of literacy must have driven the complexity of the script. Authors of inscriptions were highly-trained specialists, and correspondingly writing was used for quite a narrow range of functions (e.g. monumental, religious, etc.). In a situation of more widespread literacy, on the other hand, some types of variation tend to reduce to more manageable levels – a concept that I am working on at the moment in relation to various writing systems of the ancient Mediterranean.

I hope you have enjoyed reading about Mayan again. It may not be a writing system that we are working on directly at the CREWS project, but it is certainly one that provides important parallels for some of the writing systems that we will be researching. In the meantime, please keep coming back for the promised posts on Venetic and Roman London, as well as some ways in which you can get involved, all coming soon.

~ Pippa Steele (Principal Investigator of the CREWS project)