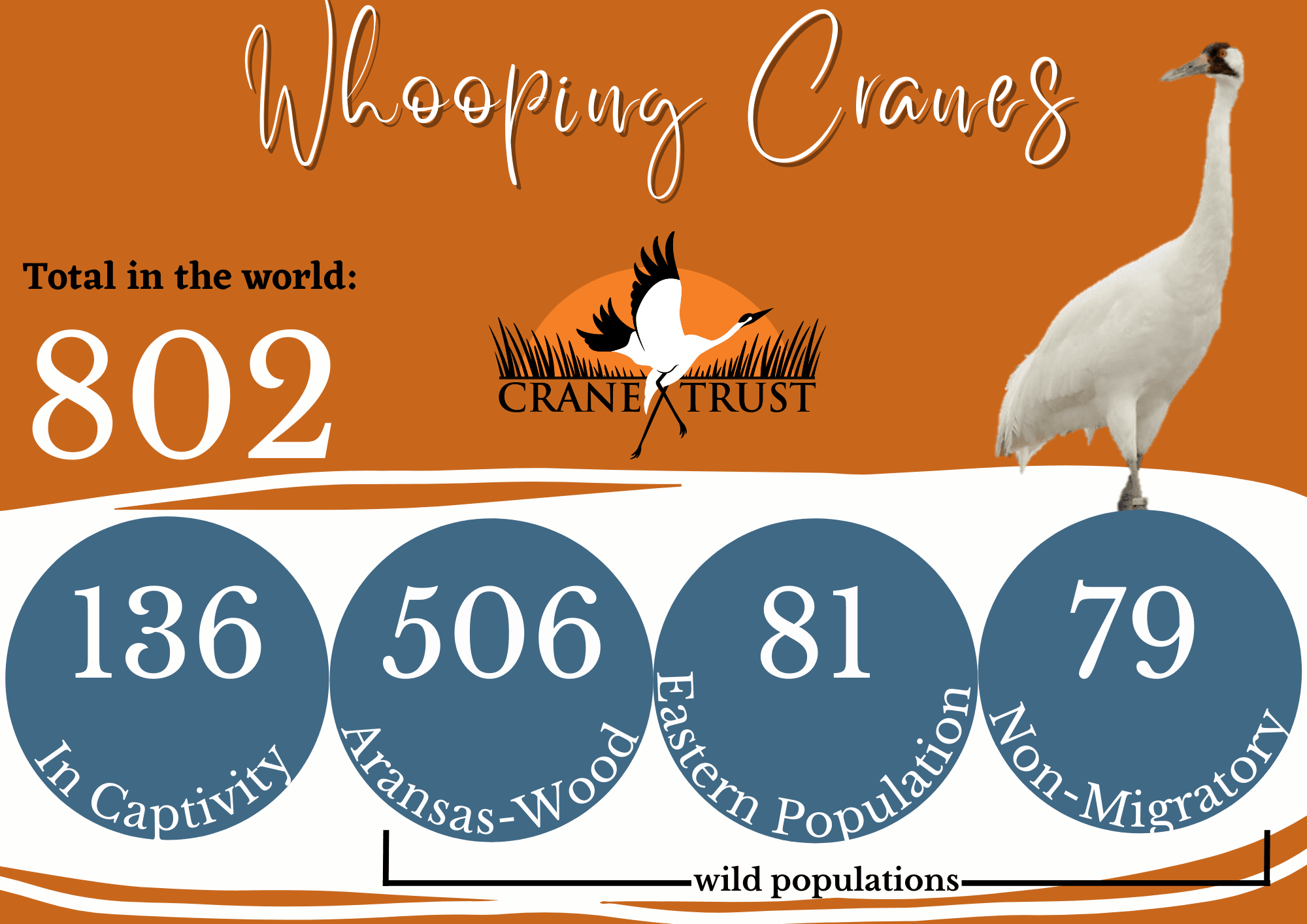

The whooping crane (Grus americana) is not only the tallest bird in North America, but also one of the rarest. There are approximately 506 whooping cranes in the wild, migratory flock that breeds in Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada and winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas.

Since European settlers arrived in Nebraska in the 1840s, there have been written accounts of whooping cranes observed here during their spring and fall migrations. Never as numerous as sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis), whooping cranes reached the brink of extinction earlier in the last century. Only 15 birds remained in 1941 after more than a century of habitat loss and continuous hunting.

After 70 years of intensive conservation efforts, the population has increased but still faces many challenges. Their intrinsic rate of increase gives them the potential to double their population size in 8 years, as happened in the 1980’s. However, environmental and anthropogenic factors (including loss of habitat, altered wetland conditions, climate change and collisions with power lines) cause the population to recover at a much slower rate.

Whooping cranes spend the winter from November to March along the Gulf coast of Texas at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Each spring from late March to late April, the cranes migrate to their breeding grounds in northern Canada at Wood Buffalo National Park and remain there from May through September. Hence, the wild population is often called the “Aransas-Wood Buffalo population” or “AWBP” referring to their wintering and breeding grounds.

Fall migration takes place from September through the end of November, when the last cranes arrive at their wintering grounds. Adult cranes that have a successful breeding season in Canada migrate with their chick(s). Whooping cranes normally lay two eggs, but usually only one egg/chick survives. On rare occasions the second egg survives, and adult pairs are seen migrating with their “twins”. In 2010, five pairs brought twins to Aransas, which was the second highest number of twins ever to reach the refuge. Whooping cranes are territorial at both their breeding and their wintering grounds and use the same territories year after year.

The migration route is long (about 2,500 miles) but narrow (less than 300 miles wide) and extends through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota in the United States, and through Saskatchewan and Alberta in Canada.

Because the cranes’ migration route is so long, the International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane (2005) designated four sites along the route as “critical habitat”, meaning that this habitat “contains those physical or biological features, essential to the conservation of the species, which may require special management considerations or protection.” From south to north, they are Salt Plains NWR, Oklahoma; Cheyenne Bottoms State Waterfowl Management Area and Quivira NWR, Kansas; and the Platte River between Lexington and Denman, Nebraska.

Along the Platte River, whooping cranes rest and feed in wet meadows, sloughs and crop fields and roost in the shallow waters of the river at night. Whooping cranes in the AWBP may make brief stops (one to a few days) on the Platte River before continuing their migration, and a few have spent more than a month on the Platte, especially individuals that migrate with flocks of sandhill cranes.

MIGRATION FACTS

- Whooping cranes migrate as individuals, pairs, family groups and small flocks (5-12 individuals). However, during the spring migration of 2007, a record number of 34 individuals were observed together at Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge, in Alfalfa County, Oklahoma (probably 4 groups), and during the fall migration of 2007 a record number of 30-35 individuals were sighted in one flock flying above Cherry County in northern Nebraska.

- On occasion, one or two individual whooping cranes will be observed migrating with flocks of sandhill cranes. These cranes tend to stay longer in Nebraska (22 to 33 days).

- In October 2010, eight whooping cranes were seen in western Missouri after strong winds blew them off course.

- Whooping cranes migrate primarily during daylight hours, but flights sometimes originate before sunrise and/or continue after sunset. Therefore, cranes can cover a large amount of ground in a long migration day and may never be spotted along the migration path. This explains why the number of sightings reported along the central corridor represents a low proportion of the total number of cranes migrating through the area.

- Radio-tracking of juveniles and subadults in the 1980’s revealed that some cranes could travel more than 500 miles in a single flight and approximately 1,140 miles in 2 days.

- Fall migration tends to be longer than spring migration. Fall migration is completed in an average of 29 days. Spring migration is completed in an average of 18.5 days.