Art In Conversation

Robert Polidori with Jean Dykstra

“I consider myself an iconographer, and iconography can have a psychological undercurrent, a deeper undercurrent.”

On View

Kasmin GalleryRobert Polidori

April 22 – May 15, 2021

New York

Robert Polidori is a photographer of human habitats, from the sprawling, “auto-constructed” cities of Rio de Janeiro and Mumbai to interiors in places like Versailles (which he’s photographed over 30 years), Havana, post-Katrina New Orleans, Naples, and Pompeii. A staff photographer for The New Yorker from 1998 to 2006, he has published 15 books with Steidl, and he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for photography in 2020. In March, a trove of contact sheets and Polaroids from Polidori’s archive went on loan to the Briscoe Center for American History in Austin, Texas. In April, his photographs of Pompeii and Oplontis, including frescoes in various stages of restoration, will be on view at the Kasmin Gallery in New York. His large-scale color photographs, taken with a view camera that produces highly detailed images, bear witness to the passage of time and comprise a kind of social portraiture. Polidori spoke to me from his home in Ojai, California.

Robert Polidori: Hello.

Jean Dykstra (Rail): Hi, Robert.

Polidori: Hi, Jean. How are you doing today? I got my first COVID-19 vaccine some days ago; actually on my 70th birthday.

Rail: Hey, congratulations. That’s fantastic.

Polidori: Yes.

Rail: Do you have the second one scheduled already?

Polidori: Yes. In a month. It’s so chaotic. The whole rollout …

Rail: Yeah it’s been terrible. So Robert, can you tell me a little bit about your upcoming show at Kasmin Gallery?

Polidori: It opens April 22. It’s images of sites in Pompeii and Oplontis near Naples, in Italy—in other words, late Roman frescoes and habitats. The first time I ever saw them was, I think, in 2009 or ’10. I’ve seen them in books before, of course, and I did some photography at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, but none of those images are in this exhibition. So, anyway, in 2017 and ’18, I spent a lot of time—over two summers—in Naples shooting abandoned churches, of which there are many. But I wanted to get back to Pompeii, so I spent maybe two days, twice, there. And I took some pictures of the frescoes, in situ, meaning how they look inside of the habitat where they were. They were partially restored, and I should explain what I mean by “partially,” which gets to the problem of making prints of these images. I didn’t really think about this when I was taking the pictures, but making “nice” prints from them is way more problematic than I ever imagined, for the following reasons: One is that, for some reason, the photographic process seems way more natural when photographing a virtual subject rather than a subject which is painted art or sculptural art already—

Rail: You mean photographing a work of art, like photographing a painting, is more difficult than photographing a room or an interior. Is that what you’re saying?

Polidori: Yes, yes. For the following reasons. One is that one is pigment chemical based, it’s like the colors that are reflected back from a painting. It’s already a modulated light. See, there’s something that’s already sort of ersatz about it. And another part of it is perceptual. When we look at a painting, we sort of reconstruct it in our mind—it’s referential, and we’re making a mental connection to the virtual scene that it’s referring to, and we sort of correct the color and accept it in a certain way. And film or even digital recording media doesn’t see it the same way that our eyes and mind does.

Rail: I see what you mean.

Polidori: The third problem here is that these frescoes are almost 2,000 years old, and they have—well, they’ve been “restored.” And the restoration has various sorts of categories. One is that a lot of the frescoes, frankly, were found as pieces on the ground, on the floor, and so they fitted them back up to the wall, like a jigsaw puzzle. So they’re basically glued or cemented back up on a wall with filler, which is just rock, concrete, or plaster. And then I think that some of the pieces were somewhat color restored, or at least waxed, and other sorts of chemical processes were used to enhance them. So there’s several levels, so to get to see the painting, you’re seeing through the various substrate stratas as well as time stratas.

So then, I shoot in film, and I shoot them in large format, because I want to see a lot of detail. And while working them up in Photoshop, which is what you have to do with any scan, you know, I’m trying to match what I remembered they looked like, and who knows how scientific that is or how objective? And two, I found myself in a kind of process where I want to show what’s left of the fresco. At the same time, I want to show those subsequent time stratas, where I want to see the concrete cracks, or the filler pieces, I want to see from one layer to another. So I want to see everything, and there are many stratas to show simultaneously. And also I guess that I enhance the color a good 15 to 20 percent, because when they put that wax on top as lacquer, it also dulls it somewhat. So because I’m making art out of something which is already art, it is a complex issue. And so in a way, to be honest, they’re like 20 percent “repainted.” It’s time consuming. It’s interesting, but it’s time consuming. I’m explaining why these are some of the most complex prints I’ve ever had to make. And plus I’m printing them on an ultra-matte flat paper, because it sort of parallels the material of the frescoes themselves. So for all sorts of reasons they were hard prints to make.

From the point of view of iconography, what I find interesting about painting of that era is that, well, when I look at the figurative part of it, say that I have some prints from this Villa dei Misteri, which is like a big house in Pompeii—

Rail: I’m looking at it right now on my computer.

Polidori: So from the point of view of the figurative painting aspects, they look pretty modern, parts of them look almost like Art Deco or Art Deco-ish, like the Art Deco movement was inspired in some way by Pompeiian or early Roman painting. But what’s different about them is their mythic structure. We’re not really tied into the Roman gods or the Roman daily life rituals. So a lot of what the subject matter content means, most experts don’t know much about. However, the way that the people look, it’s like, “gee, that reminds me of a face I saw two weeks ago.” [Laughter] So in 2,000 years, the human body hasn’t changed all that much. I can relate to these individuals as being people that I could almost know, but what they’re doing, I don’t know anything about. So I guess cultures can come and go, but biology remains.

Rail: Right.

Polidori: Or physiology remains. And I also see that in the way that they’re painted, you see, basically, what Renaissance painting comes from, but the myth structure has been replaced by Christian myths.

Rail: It’s interesting, because in describing your photographs in Pompeii, you’ve already touched on themes that seem to go through a lot of your work. I’m thinking of Versailles, for example, and the problems and issues inherent in any restoration, and what those say about the culture doing the restoration. And then, this whole idea about memory: you said that part of the problem with taking a photograph of a painting is that when you’re doing the color correction, it’s somewhat based on your memory of what the colors looked like. So there’s this whole issue of memory that’s inherent in what you’re doing, too, not just yours, but the memories held in these rooms.

Polidori: I think it’s true, even of the restorers—there’s a sort of guessing at what it looked like, with everybody guessing or interpreting. But there is one difference, though, a structural difference, between the work that I did in Pompeii and Versailles. One is that Versailles, for me, is about historical revisionism as seen through museum curatorial choices. And when I say historical revisionism, I’m talking about the fact that Versailles lived through a lot, through several centuries and several regimes, and even during the time that Versailles was a seat of government, rooms had gone through several treatments. And curators are constantly restoring for this time period, that time period, or another, or a combination thereof. Where the French government and their curators are mostly knowledgeable about what they’re dealing with, in Pompeii, it only takes a generation to lose contact with your past myths and history, and they don’t know all that much about it. Not much is written about it, so instead of being historical revisionism, exactly, they’re wondering what it’s about.

Rail: Right. Trying to figure it out.

Polidori: It’s like imagining a past, where with Versailles, it’s about resuscitating a past.

Rail: I see what you’re saying.

Polidori: My Versailles work is popular for some individuals in America, but it’s not popular in France because they see what it’s about and it bothers them.

Rail: Oh really?

Polidori: Yeah, it’s the same thing with the work that I did in post-Katrina New Orleans. It’s popular all over the world except America.

Rail: And so when you say “they see what you’re doing,” you mean they perceive a kind of inherent critique?

Polidori: Well, they see that it’s about historical revisionism. In the 1980s when Mitterrand was the president, he was a Louis XIV kind of figure. Well, ha, guess what? They restored a lot of Louis XIV. And then when Sarkozy was in power, well, guess what? They liked a lot of Louis Philippe’s stuff, because he was more like a guy that comes from Long Island. So it’s like fashion.

Rail: Yeah, sure.

Polidori: Every present moment in history has favorites of the past that it likes to hold up for admiration, and it has others that it dislikes.

Rail: Right. Well, what do people in this country see in your post-Katrina photographs that they find problematic?

Polidori: Well, America is a Protestant country. Protestants don’t take so well to pathos, so they think that I’m a reactionary, because I am making misery look beautiful. And so because of this, I am minimizing the plight of the victims. I only get this in Anglo-Saxon countries, the rest of the world doesn’t think that way.

Rail: Right. And so what’s your answer to that criticism?

Polidori: My punk answer is, “Well, if I made it ugly, would you look at it more?” And my more serious answer is, this is a problem created by wanting to fix political blame as the cause of events. In America, the prevalent culture says that if things go bad, it’s your own fault. Therefore pathos is problematic. In art history, with Ruskin, there’s the notion of the “pathetic fallacy.” You know, it’s like when they say in English, “Gee, that’s pathetic,” and it’s actually a contre-sens; it’s an ironic statement. For them pathos or being pathetic means kitsch. It’s below consideration. And this is also why they call what I do “ruin porn.” But it doesn’t have much to do with pornography at all. It’s about death. So that’s why some of my work is not always appreciated in America.

Rail: They’re also maybe missing a larger societal critique in the work, which is that these things happen for reasons other than a person’s individual choices. And that’s maybe what people don’t want to reckon with.

Polidori: Yes, but there’s another thing, too. When I came back, because I worked for six months on that project, and when I made the book, my publisher, Steidl, he knew a curator at the Corcoran in Washington, DC. So I did a book launch at the Corcoran, and I’ve never lived in DC, okay? And I didn’t realize how intensely political it is. So basically, I was faced with an audience, an ultra-liberal audience that was waiting for me to say that, you know, it was all George W. Bush’s fault. You know, I’m not a Republican. Okay? And I actually lived in New Orleans during high school. But I can tell you, whether it would have been Clinton or Bush, the outcome would have been identical. And then, you know, when I said that many members of the audience just walked out.

Rail: Really?

Polidori: Yes. Okay, so much for Washington. [Laughter] That’s a tough town. They say how tough New York is but, hey, DC, it’s tough, man.

Rail: Yeah, it’s a strange place. [Laughs]

Polidori: Yeah, they’re not looking at art; they look at art as being a vehicle of a set of ideologies.

Rail: Right.

Polidori: Okay, so, anyway, let’s get back to Pompeii. Another fascination that I have for those Pompeiian interiors is that those paintings were made, or so historians think, as “memory theaters.” You know, they wanted to live a mythic life and the subject is already about memory and the perpetuation of mythic memory.

Rail: What do you mean by memory theater?

Polidori: Have you ever read the book called The Art of Memory by Frances Yates?

Rail: No, but I wanted to ask you about it because I read a reference that you made to it and I was really interested.

Polidori: Okay, mnemonic systems were used in antiquity, and the Greeks brought it to the Roman world. This is known through some remaining texts. And the curious part of memory theaters—and they were called memory theaters. Why? Because strangely enough, to remember something perfectly, paradoxically, you have to remember two things. So I’ll give you the example. Students of the art of memory—Pythagoras was also a practitioner—had to remain silent for two years. You weren’t allowed to speak and you’d have to memorize empty rooms, which were called locus, and then you’d have to put strange, out-of-the-ordinary images inside because the mind remembers things out-of-the-ordinary more easily than the banal. It remembers exceptions more than everything that fits the general rule.

Rail: Right, they constructed a sort of memory room.

Polidori: And in these homes, they would make memory rooms of their myths. So even Versailles was structured to be a memory theater. This is an idea that came from the Italians. This wasn’t a French idea, it was Florentine.

Rail: It’s really fascinating, this idea of the memory theater. I’m looking at some of your photographs from Pompeii, and they’re incredibly beautiful. They really do capture all these layers that you’re referring to, because although there are metaphorical layers, there are physical layers, too. You can see multiple layers and into these different rooms, so that the subject matter reflects what it’s about metaphorically, too.

Polidori: Well, good. Yes, that’s what I’m trying to do.

Rail: Can you tell me a bit about how you got started as a photographer to begin with? Weren’t you originally interested in film?

Polidori: Yes. Well, I always had a respect for photography, a respect for the camera. I feel that it’s—I won’t say a magical instrument—but I like that by using the laws of physics, you can make the world’s own iconography. So I was always sort of seduced by that idea. I thought that was the modern way to make art. It’s a different philosophy. I’m proud to say that I don’t consider myself a creator, I’m a medium. I don’t invent anything. And I don’t pretend to invent, but what I do is I channel stuff, I discover and channel stuff. But I take it from the real world. It’s not totally devoid of me, but it’s not only me.

Rail: Right.

Polidori: I was 18 years old when I had one of the greatest aesthetic shocks in my life. Seeing Michael Snow’s film Wavelength (1967) changed my life. And that’s a film about the experience of temporality. Michael Snow, he’s not so famous in America. But strangely enough, he’s the most popular in France, and in Italy. He’s a grammarian of modes of perception. So that got me involved in that whole group of the American avant-garde. But to get back to what I said earlier, when I read that book, The Art of Memory, I realized the simple power of the still image. In those days, it didn’t look as good on film as it did in a photograph, because the grain moved, it looked too jittery in film. That’s changed, but in those days, like in the late ’60s and ’70s, it looked better in a photograph and you can live with it. Films can impact your life, but you don’t live with them in the same way.

Rail: Were you always interested, from the beginning, in this kind of social and psychological portraiture of interiors or neglected or decaying spaces?

Polidori: Yeah. And I even look back at some of my earliest photographs that I took, when I wasn’t at all self-conscious of what I was doing. I always had a bent in that direction. Jean, you know, I guess somehow, intuitively, I knew that I was going to live in a time period that was going to be the end of industrialism. And I would say a greater subtext of all my work, it’s about the end of the Industrial Age.

Rail: Right.

Polidori: Another thing I want to say, and from a practical point of view, I always thought, well, I wanted to make it as an artist, but I thought if at least I take photographs of the social environment, as it’s changing, they’ll at least have value just as documents. I was hedging my bets.

Rail: In fact, although your photographs have value as documents, of course, they’re obviously also about formal concerns: the composition, the color, the way you use the geometry of the space within the frame. They’re beautiful pictures. Can I ask about the work you call “dendritic cities” or “auto-constructed cities”?

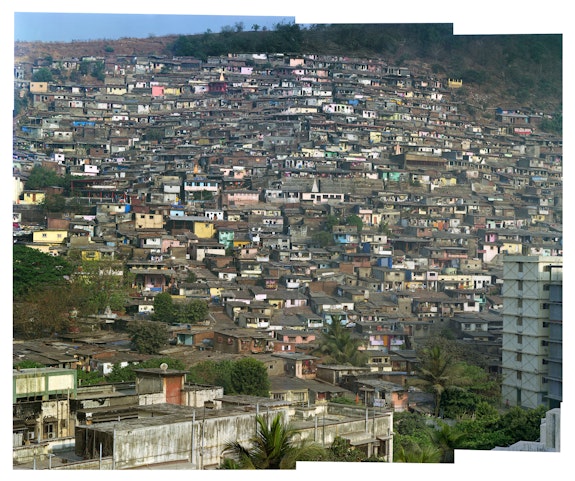

Polidori: I’m interested in habitat. Pompeii was a habitat. This term “auto-constructed city” was invented, or coined, I should say, by a Brazilian sociologist. And it means sort of what it says. They’re cities whose houses are built by their own inhabitants.

Rail: Right, they’re not planned.

Polidori: They’re not planned. Here we refer to them as slums, but do we have slums? Yeah, most of the auto-constructed cities are slums. This is true. But in America, maybe the only example is now these tent cities that you find, like in LA, but these people are living in tents, and they’re not building a whole lot. Because slums in the United States are usually where disenfranchised classes move into pre-existing housing which was left by a more advantaged social class that had sort of moved on for one reason or another. So they don’t need to build their own housing, or they simply don’t have the means to, where in many places around the world, like in Brazil, like in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, what happened there was that with industrialization and the modern capitalist regime, people from the hinterland would come to the metropolitan area, and they wouldn’t have money, and so they basically squatted on land that was deemed non-exploitable by the prior residents of the city, or the more affluent, like say, in Rio. See, when you get inclines of 30 degrees or more, it’s hard to make houses there. And just to get there, it’s a lot of exercise to get in and out. So they would squat on that land, and they made their own houses. And also in Mumbai. Yeah, where they’re not so much on hills, there they’re in troughs, where houses were never built, because when a monsoon comes, they flood. So people with money don’t want to build their houses there.

And this kind of housing is all over the world. I would say 30 percent of the world’s population lives in this kind of housing, and I find it sort of interesting because I see them as a true type of organic growth, where the more affluent class, they get pre-made industrial houses, you know, made by architects and engineers and with the gridded plan, the gridded Cartesian rational planning, okay? So I see it as kind of an organic versus manufactured force.

Rail: And in your mind what connects your photographs of these kinds of organic, sprawling, urban areas with the interiors?

Polidori: Well they’re habitats. I’m interested in habitat as a psychological force. For some reason human beings went back to a womb life, we retreated to the womb, we’re cave dwellers, and we make inside dwellings. So we retreat to an interior world of our own making. So for me, they used to call me an architectural photographer. I sort of know how to do that, but to me, architectural photography is just product shots. See, what interests me is what human beings do to architecture. And how they use it and how it shapes them. And then, in some of the more fantastic examples that you mentioned in Versailles and in Pompeii, they become self-conscious of this need, of what Freud called the superego. You put on walls, what you want to be or what you think you are.

Rail: Right. And in a place like Pompeii, it’s a historical investigation of the psychological state of a group of people so many years ago, it’s fascinating to try and figure it out.

Polidori: Yes, but then again, the amazing thing is when you look at the people’s faces and their bodies, they look like people left today. I don’t think the Romans lived so differently than us except they didn’t have electricity and they didn’t have flight. But they had everything else.

I consider myself an iconographer, and iconography can have a psychological undercurrent, a deeper undercurrent. You know, abstract art, there’s nothing wrong with it, but I don’t find it all that deep. And a lot of contemporary painters that are representational, when you examine their paintings, it turns out that they took a photograph first, and made the painting from the photograph. So many of these artists, they say, I’m only using photography. My retort is, “I’m only using art.” They regurgitate photography; I regurgitate art. This thing of only using photography—they are being psychologically dishonest with themselves.

Two artists that I’ve rejected are, one: Marcel Duchamp. I reject the depth of importance of the readymade—it’s facile, a clever after-dinner musing of the haute bourgeoisie. And two: Andy Warhol, for the same reasons. His work has the visual vocabulary of commercial advertising, and I reject that it’s as deep as they say.

An artist who has influenced me is Bob Dylan; he’s an iconographer of words.

Rail: So much of what you do, Robert, seems to involve travel for your work. What’s it been like to not be able to do that for the last year?

Polidori: Yeah, that’s been different. Well, it turns out that just a few months before COVID-19 hit, a collector purchased most of my archives, other than my negatives and digital files, which are now on loan to the Briscoe Center at the University of Texas, in Austin. So, you know what they say, that when you die you see your whole life go in front of you in a few seconds. Well, this is like I’ve seen my whole life go in front of me in about a year and a half.

Rail: Right. [Laughs]

Polidori: So it’s been kind of a review. And I’ve just been stuck here, in the studio, but I don’t really mind. I mean, it’s different, but I didn’t go out and make photos about the wearing of masks and all of that, I really think that, for me, first of all, I’m not so young anymore. And it more or less deals with the inevitable problems of facing death and what that means. So I’ve been forced to review my past work. It’s been like a review.

Rail: In order to prepare the archive to go to this museum?

Polidori: Well, you know, what happened? I haven’t parted with my negatives. But they took my contact sheets, press prints, and Polaroids that I used to use as exposure tests, in the days when Polaroids were still available. There’s about 30 years worth of that. So now, I have to reorder what’s left. And by doing this, it’s been a life review. But I want to say, stepping back from this period, I really think what this period, for me, means is a kind of acceptance; there’s no escaping this COVID-19 thing. And it’s been all over the world. It’s one of the few times in my life where everybody in the world is going through the same thing. Almost everybody in the world. And so that’s different. Because there’s no escaping it.

Rail: It sounds like you’ve been very productive, though. You had this project to do in your studio, which is kind of nice timing. If it’s possible, will you come to New York in April for the show at Kasmin Gallery?

Polidori: I’d like to and I miss New York, you know? I always love New York.