Art In Conversation

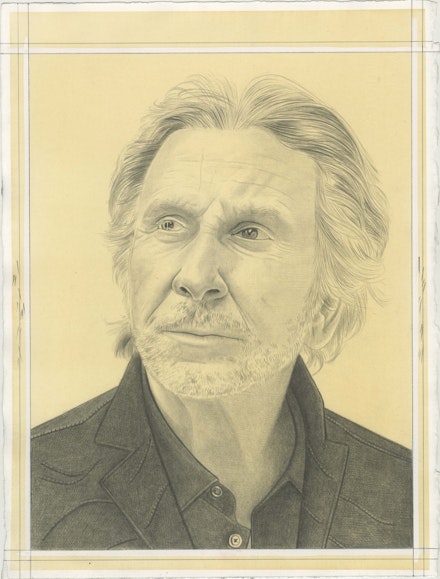

BERNAR VENET with Robert C. Morgan

“I think an artist should never have a sense of a work before they start to make it art. We have to be adventurous and just try, allowing our personality to take over.”

New York City

KasminSeptember 12 – October 12, 2019

Bernar Venet is an internationally renowned artist, born (1941) in southern France who has been called both a sculptor and a conceptualist. Throughout his extensive, highly prolific career, he has made a concerted effort to bring form together with ideas. Rather than detach one from the other, he insists on the viability of both as integral to the creative process, often on a monumental scale. This was revealed in his recently completed Arc Majeur on a major highway in Belgium, a project on which he began working more than 30 years ago, prior to its completion on October 24 of 2019. In addition to his steel and concrete monuments Venet has worked extensively in other media, which include painting, drawing, performance art, and a particular style of mathematical poetry.

On the occasion of his recent exhibition/performance at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in September 2019, the staff was kind enough to arrange a comfortable space on the second floor of the gallery at 293 10th Avenue in West Chelsea for an interview. It was 11 o’clock in the morning on September 14 and later in the day the full moon would reveal itself. The energy was intact. The artist, who had spent several years in lower New York throughout the development of his early career was kind enough to speak in English, which at times became challenging but always in keeping with the ongoing tempo of our exchange.

Robert C. Morgan (Rail): Let’s begin from the beginning, I wanted to ask you where you were born and when you first discovered yourself as an artist.

Bernar Venet: I was born in a small town called Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban, in 1941. I was ok at school but academic studies were not interesting to me. I was very sickly and I missed about one day out of three.

Rail: I am familiar with that. I grew up with asthma.

Venet: It was really bad. I had an obsession with drawing and making paintings and around the age of 11, I had my first two important experiences. One day, I made a drawing at school and my teacher, who had never shown any interest in me, said, “Did you make this drawing?” I replied, “yes, sir” and he said, “It’s fantastic! Can you make a bigger one? We should put it on the wall.” That was the first time that someone showed a level of admiration for my work.

Rail: How old were you at that time?

Venet: I was 11. There was a painter in my village called Marinig, who was making paintings of flowers and seascapes. It was all very commercial, but for me, at 11 years old, he was an artist. And so, my mother introduced me and I showed him my drawing and he said, “oh this is very good! In three years you’ll be as good as me.” I thought, “oh my god!” And so I started to paint and paint, copying his paintings or any image that I could find. The big moment came when my mother took me to the city of Digne in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. We took the bus and went to a shop where they sold books and art supplies. I chose some oil paint because I understood that this painter (Marinig) was using this medium so I thought that in order to be like him, I must also use oil paint. We chose five or six colors and while my mother was paying, I went back outside and looked in the window where there was this book, with a reproduction of a painting of a woman washing her feet in a stream. On top of the book there is something written which I didn't understand: “RENOIR.” So I went back to the man and asked “what does Renoir mean?”, “Renoir is a very big painter” he said “very famous—an Impressionist.” That didn't ring a bell for me and then he said, “he’s famous, he is in museums all around the world, his paintings are worth a lot of money, and look there are many books on him.” This was the day that I understood it was possible to make a living out of being an artist. At this point my whole family: my grandfather, mother, father, and brothers, were all working in the village factory, and I thought for the first time perhaps I could do something different. So, of course, I put all my energy into art. I was lucky because very early on, at the age of 11–12, I understood that there were artists that were part of art history, as in, they were making history.

Rail: So at this point you began pursuing art seriously?

Venet: Exactly, I became obsessed with it. And luckily there were some lecturers that would come to the city—I remember one about the Impressionists; I was around 13 years old, my mother took me there, she was really good at putting me in the right environment, buying books—I was only reading books on art, the life of Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Goya—I knew everything about those guys in those days when I was 14–15. Then I heard a lecture by René Huyghe, a very big art historian in France who wrote a book for Skira about Modern Art. I was obsessed with discovering this new world, and I already understood that creation was the most important thing.

Rail: I remember you telling me that at one point, while you were in Algeria during the late ’50s.

Venet: 1961–62.

Rail: You somehow convinced one of your officers to give you a space where you could make art, I thought that was quite extraordinary. I can’t conceive of something like that happening in the American military.

Venet: Yes, we were at a place we called the Center of Selection where younger people would come to pass their military tests and then be sent to whichever faction they had applied to—aviation, marines, infantry. It was in the city of Tarascon and as soon as I arrived, I realized that there were some huge lofts which were totally empty. One day I asked the corporal, do you think I could use one as an art studio? He said “A studio? You’re in the army! Go ask the Captain!” I went to see the Captain and he said “I can’t give you permission, you have to ask your Colonel” and so I went to see the Colonel. I introduced myself and I lied that I had a contract in Paris, I had exhibitions planned and that I needed to paint. While my friends would go have beers in the evening after finishing their duties, I would go to the studio and work on my art. He said to me:

“Eh, you are an artist huh? What do you do?”

I said: “Art, it’s very special, I paint with my feet.”

“Are you making fun of me?”

I said, “Oh no sir, it’s modern art.”

“Oh, like Picasso?”

I explained, “Not quite, Picasso is figurative and I do abstract.”

“What do you mean? What does that mean?”

So I ended up giving him a course on abstraction, beginning with Malevich till the present.

Venet: He said: “Take it, but I will be watching you, ok?”, and I got the studio for 10 months. I was not doing much work in the Army; I was just doing my thing, making my art.

Rail: Fantastic! It occurred to me this morning that one year ago you opened your exhibition in Lyon, your retrospective curated by Thierry Raspail. Today, one year later, here at Kasmin, how do you reflect on this retrospective in terms of your career?

Venet: I think that I couldn’t have done a better retrospective because of the amount of space. I had the entire museum and this allowed people from France and beyond to discover how my work evolved. People know my sculptures really well, but they don’t usually know where they originate, they might not know about the original reliefs that came before the paintings or even the tar paintings, and what I did in the Army at the very beginning. The evolution of my work, the breadth of the exhibition, was very important, and that's why this exhibition was so well received.

Rail: You were given the entire museum, am I right?

Venet: I had the entire museum: I had all the three floors plus the ground floor with wall paintings and furniture as well. I really had a lot of space, and the show looked serious and spectacular at the same time.

Rail: Let’s go back a bit to when you were doing your exhibition, called Five Years in 1971. I think you were in the United States at that time, weren’t you?

Venet: That exhibition covered precisely everything I did from 1966 to the end of 1970.

Although I had produced a lot of work already, in those days I had such a radical vision of art that I was keen to forget about the tar paintings and the Pile of Coal, even though today they are so interesting and significant in the context of that period. I was just thinking that anything related to formalism is not interesting, so that’s why we did the Five Years show. And that starts with the first industrial drawings and diagrams, which ultimately showed the evolution of my work that dealt with different scientific disciplines.

Rail: I remember there was a very early painting from 1966 called La droite D’représente la fonction y=2x+1, and you were trying to show the line for what it is—a line. You were very interested in the monosemic idea in art. By the end of that Five Years, if I recall, you were dealing with the linguist Jacques Bertin, who introduced you to the idea of monosemy [singular meaning], and how that differed from polysemy and pansemy. Apparently that was a big step for you to understand that you were looking at the line as a line, not as a representation or an expression. And this was opening up new territory for you, which was maybe closer to science than it was to aesthetics.

Venet: I can be very precise about that. You see I started to make those mathematical diagrams intuitively, in 1966. I had no predetermined feelings about it when I started. I think an artist should never have a sense of a work before they start to make it art. We have to be adventurous and just try, allowing our personality to take over.

Rail: I call that the mistake of the a priori theory.

Venet: Absolutely yes.

Rail: It doesn’t belong in art.

Venet: Only people who copy others have pre-existing feelings about their work. In those days, all I knew was that if mathematical diagrams could one day be accepted as art, then there was something different happening because I wasn’t making figurative art, or abstract art, at least not in the way we think of it today.

Rail: …polysemy and pansemy?

Venet: Well at that stage those two words did not exist in my mind. I was just intuitively going in a direction that was unknown, let’s say, and that was really my goal. Once I decided to stop making work I still had difficulties articulating precisely what my work was really about. I had to get involved in doing it. Some critics were trying to justify the fact that what I had been doing was art that seemed to solely focus on trying to find relationships with things in the past. I said “no, there is no relationship between the past and me; this is like a cut, as radical (I hoped) as what Malevich did with the black square or Marcel Duchamp with the readymade.”

Rail: They were the same year, you know. The black square and the first readymade both happened in 1913.

Venet: Yes, yes. So I wanted to make a break like that, and the day that I discovered from an art magazine—a text by Jacques Bertin. I read this text and suddenly I understood what he was suggesting. He was proposing three different categories for visual images. Some were figurative, and he called them polysemic, others were abstract and he called them pansemic, and then, he said, there is a world of diagrams and maps where things are being presented in a very precise way—there is no confusion, no ambiguity; there is no possible misinterpretation, you know, they are giving you precise information. And suddenly, I said “this is it! Pansemic, polysemic ,and me, I am monosemic!” And I remember thinking that just the same way Yves Klein was monochrome—I was monosemic. This was a definition for my work.

Rail: Well it opened up a possibility for you obviously.

Venet: For me and possibly for others by showing that it was radically different and not related to artworks of the past. But it was only in retrospect that I felt any need to demonstrate that my work was entirely forward facing and not related to anything in the past.

Rail: Your exhibition of the Five Years project was shown at the New York Cultural Center. It was located up on Columbus Circle. I remember there was a catalog for the exhibition that I poured over when I discovered it some years later. If I am not mistaken, Donald Karshan was the curator of that show. It was one year after the Information show at MoMA curated by Kynaston McShine. But you seemed to question McShine’s idea, by suggesting that Conceptual Art was really about scientific inquiry.

I think that was a whole new take on everything that was shown at MoMA; it was a kind of a turning around, to rethink what the term might mean from your point of view, which I found completely interesting. And also, I think you borrowed the idea, you can tell me if I’m wrong, of Duchamp’s readymade in asking scholars, in physical science and so forth, to lecture. In other words, you weren’t doing the lecture, you were asking them to do the lecture—I mean it’s sort of like a readymade situation in a way.

Venet: Yes, but you know my story with Marcel Duchamp?

Rail: You were talking directly to him?

Venet: When I was 27, I met him and I took this opportunity to develop the idea that my work was, in the context of art history, a lot more radical than his work.

Rail: Oh I think you told me this.

Venet: Perhaps without Duchamp, certain gestures from artists would not have happened, but I don’t feel very connected to him, you know, because he was still dealing with the real world, with objects that could be painted by Van Gogh, by Chardin, you know a bottle rack could very well be in still life of Chardin or Van Gogh or Cézanne, where a mathematical equation could not be in a still life of those artists. And I was also introducing people who were not in the art world. Not using actors who are artists and putting them on a stage to make a performance that was actually a larger proposition. Yes, you can say it’s related to Duchamp because we take something outside and put it in the context of art but I was going way beyond the object. In one exhibition at Daniel Templon, in 1989, I created an exact replica of the factory where I make my sculptures. I brought everything from the factory: the steel, the workers, and we just ground, burned, and cut the steel. This was all I was presenting, it goes well beyond just the object.

Rail: Of course, I understand that. Then after 1971 there were six years where you didn’t really produce much related to art. You took a hiatus from art, and I think that lasted until 1976 if I’m not mistaken.

Venet: Yes. The reason I stopped was not because I was discouraged or because I had no more ideas, it was because I thought that I went as far as I could in the context of objectivity and rationality. You know, by 1969 I was getting to a point where in order for me not to make a predetermined aesthetic choice on the subject that I might present, I was going to Jack Ullman at Columbia University saying “Jack, tell me about a radical new science book, and I’ll present it as an artwork.” So he would make the choice and I simply sent it on to the curator of the exhibition. Jan van der Marck for Art by Telephone at The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 1969 for example.

They would make a blowup and present the work and I would not even go to the opening, just to show the distance that there was between the artwork and myself. So I was trying to push the limit as much as I could. Then when you do that and you get to that point, what else can you do? This is it; I had gone as far as I could.

I thought that there were three career periods for an artist: one when you’re learning, and one when you’re producing, and then there is one where you can easily just go on copying yourself. I was certain I didn’t want to go down that route. An artist who copies other artists is bad but an artist who copies himself is equally bad. So we have to keep on moving. If we can’t move, we have to stop. So I stopped, and started to define the true nature of my own work. This is when I discovered Jacques Bertin and his thoughts on categorization that I mentioned earlier.

At this time in 1976, I thought I was giving up forever and I couldn’t imagine coming back and doing anything more radical or different from what I’d done so far.

But what happened is that I worked so much during those six years, testing the limits of what I had done before, that suddenly I realized it was now possible to do something else. I resisted and resisted and then one day, I remember being in Connecticut visiting friends for the weekend, and suddenly, I just knew I had to go back to my studio in New York, and be alone, and make a painting. It was entirely visceral and I did exactly that. I abandoned everybody: my wife, my kids, and everyone, and I went back by myself to Manhattan. I was on West Broadway and I made my first painting; a triangle with the measure of one angle.

Rail: Yes, yes.

Venet: And I thought “Okay, look. It’s an idea: I’m not going to show anybody, I’m gonna make some drawings,” and then for two, three, four, five months I worked on a lot of them. But I was not showing them to anybody, as I was not sure this work was good enough to deserve attention. Until the day Jan van der Marck, again, the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago came to visit me. He was a very, very close friend. And I said to him, “Jan, I have a surprise for you and I’m going to show you what I have been doing recently.” He was so surprised that I had started making work again. I showed him the new paintings and he said, “Bernar this is fantastic, I’d like to invite you to documenta ’77. You will be part of the show.” So I thought, “oh, look if I am at documenta then I am going to show my work to everybody.” And then I just kept on working. I moved very quickly—to find new formal and conceptual directions.

Rail: But that’s typical in a way. In terms of your situation, particularly coming from France and that kind of exposure that you were having and so forth. Listen, let’s move ahead a little bit because I’m very interested in, I don’t want to load this with the word “dichotomy,” but you know often you are introduced as a conceptual artist, still at this point. And sometimes you were introduced as a sculptor and I think in the essay that I recently wrote, I tried to deal with that issue because I don’t think it’s either-or in your case. I think they are inextricably bound to one another from my point of view. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Venet: Yes. I have the tendency to now say that I am not a conceptual artist. I used the term originally in connection with the way other artists used language as a rejection of anything formalistic.

Rail: Well anything that was formed.

Venet: Yes.

Rail: That was my objection in my essay actually.

Venet: Yes, yes. Well but originally this is how I thought.

Rail: I see.

Venet: Any formal issue was to be completely negated, you know, refused. So only the use of language was the real, pure, hardcore Conceptual Art . Since then Conceptual Art has had some good influences, but also some bad ones.

Rail: I agree with you.

Venet: Yes, some very bad ones. But anyway, of course concepts are still the origin of my production because you see it’s not just taking a piece of steel and bending it and saying, “Hey, that looks good. That’s original.” No. I have concepts, I have order, disorder, Effondrement (collapse) and transition. If you look at a selection of my work, you can see that the material, say the line, might be what I use to make my proposition visual, but it comes from the concept. When I do a collapse, it’s actually physically collapsed, that’s why today my sculptural practice is open to so many possibilities. I can do things with arcs, I can do it with angles, with straight lines, indeterminate lines, you know, there’s control or no control. These are the concepts that direct all my work. That’s why it’s so open.

Rail: In your exhibition at Kasmin you’re dealing again with indeterminacy, but we are looking at work of yours that is earlier, probably from the early ’80s?

It’s great to see that. It’s important work, and it hasn’t been seen together for a long time. I think that the Indeterminacy works precede some of the later concerns—with the measurement of the arcs and so forth—that came into your work very strongly in the ’90s and then into the 21st century. I think there are many viewers who identify with your work from the Indeterminacy period. It’s interesting that after this you moved into something more geometric using the arcs. Here you gave the dimensions by embedding the degrees of the arc into the steel. In more recent work, you are giving the weight of the steel as well.

Venet: I guess I started my real activity as a sculptor with those “indeterminate” years. It took a while before I really started to present the arcs and even longer before I began to present the angles that I exhibited at Kasmin two years ago. I’m also making structures with straight lines. So, I really work on all four of those possibilities. The first Effondrement [Collapse] came with the arcs, but then one day, I thought, “Wouldn’t it be more original to make Effondrements with the angles?” And so, all of a sudden, I am doing the Effondrements with angles and straight lines and even those classic Indeterminate Line pieces from the earlier days, there is one that is sort of stuck, collapsed a little bit… If it fell onto the floor, I would leave it the way it is.

Rail: You don’t like the idea that it’s controlled?

Venet: I don’t. Nature is doing the work yet the concept is in my control; it’s not in the mind of nature.

Rail: Of course, yes, I like that.

Venet: Nature is just doing the job.

Rail: Nature is always in motion. When I saw the Effondrements while visiting you in Southern France, one of them was based on some of the elements that you used in your Versailles installation. You placed these indeterminately in relation to the ground rather than ordering them vertically. I thought it was one of the most important pieces you’ve done in recent years. I remember how I felt when I first saw this work, and frankly I wasn’t the only one. Other people visiting at that time said the same thing. What accounts for that? Why is it so strong? I have my own ideas, but I’m sure you were feeling something similar when you were creating it.

Venet: I love to hear that. The success of that sculpture is certainly coming from the scale. It’s true that I knew that they had those 16 arcs that were 20–25 meters long, and then I had this piece of land and I knew that I had to do something. I remember working on maquettes—this is how I work—and if it’s really good then I take pictures, if it isn’t good I create another one, always with 16 arcs, exactly the same proportions as this one. There was one that, to me, was really looking like a mess. I didn’t try to put one piece after the other, I was really respecting the nature of the collapse. I insist on that… What I’m doing is reconstructing, but let’s be honest: you can not safely do an actual collapse of steel at that scale.

Rail: Just to clarify, because I know what that was before it was an Effondrement. It was upright, vertical, whatever you want to call it, but the weight and the dimensions of those arcs were impressive to begin with. Clearly it was not intended as accidental, at least not from my point of view. Getting back to what you were saying in regards to Conceptual Art, I think you were referring to an earlier period in the late 1960s when language took superiority over form. It was not just chance operations. It was more than that. I could sense a conceptual inquiry embedded in this work where I could relax and see this piece as a total experience... I think the relationship of form to your work is not in opposition to concept. As I stated earlier in my essay, I think you are one of the first artists who, in effect, rejuvenates the use of concept in direct relation to form.

Venet: You say it better than I can. It’s really a successful piece, it came out so well. Now I only have one obsession, and it’s to make two more of that same quality for next summer.

Rail: I see. Do think they’ll be the same scale?

Venet: I’m thinking slightly smaller, but with more weight.

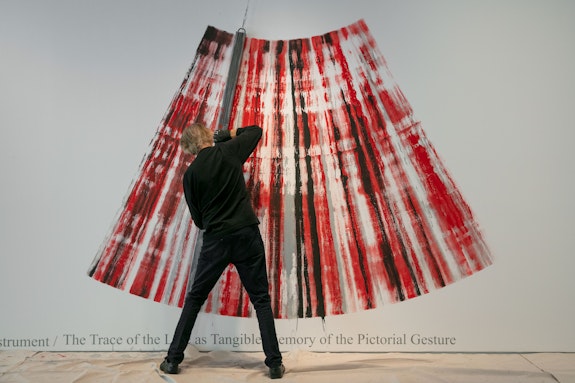

Rail: Let’s talk about the piece you did as a performance at Kasmin in West Chelsea. I was very taken by it probably in a different way from others, but I think that you have a history of working from the point of view of these singular steel bars. When I walked into the gallery and saw the steel bars hung horizontally at midpoint on the wall, I hadn’t really looked at the other completed works very closely, and given the number of people crowded into the space, it was difficult to focus on what was going on. I just let it happen. Maybe this is an American issue—I don’t know if you see this in France—but a lot of people were buzzing and talking, and frankly I don’t know to what degree they were focused on your performance.

Venet: I, too, was disturbed by the people talking so much. I could have said “shut up” but I didn’t want to, you know?

Rail: Yeah, it was a bit annoying. In performing this wall drawing, it was an opportunity for people to see how you work. Given that you have done very few of these performances in the United States, this was a rare occasion for people unfamiliar with your work to see how you do it.

Venet: I’m really happy with those pieces. The one that I did on the day of the opening came out really nicely. It was the best one I did. I made one the day following the opening, but this one in particular came out very well. It’s an interesting experience. Again, it’s just that I’m trying anything I think about in relation to my work that seems to be relatively different or new. Only time will tell if it was worth making this, but I don’t care. You know, when a writer is writing a book, they can make a mistake, but then they can just take away a page or two. You correct what you are doing. I still think it’s a beautiful experience to do that, and I like the idea. The piece in the gallery is something that I’ve shown before. You have the cables and the bars that were already in my work. In fact, when you look in the catalogue you can see that I exhibited that many many years ago in other places. I like the idea of using my artwork as a tool to make another artwork.

Rail: I think that the manner of work is something we’re kind of losing touch with because everything is on the keyboard now, and this is a kind of physical engagement—or what I’d refer to as technal, which I think is absolutely essential for art, even if it’s within the mind, even if it’s arbitrarily within the mind, there’s video work that I’ve seen that has that technal sensation, because I can tell that the artist is embedding the sense of touch through thought, and I think we’re at a point now—and I’ll let you talk about this—where are we going in terms of the way artists will work?

Venet: If I knew the answer, I would do it right away.

Rail: Well, certainly in this country, and in China to some extent, there are artists with many paid assistants who are essentially doing the work—and I’m not being critical of that per se. Rather I’m just wondering if it is correct to call that work “conceptual” because someone else has thought of it while others were working to realize it (for very little money). Is this going to be the future or do you think there will be a turn-around?

Venet: You don’t know, there could be a period of production of art, like making a painting, or performances after that period in the late ’60s, which was so creative. It’s so difficult to make gestures again, the parameters of what constitutes something as an artwork will continue to change. Artists in 10, 20, or 50 years will come up with new ways to think about art. Art has existed for many centuries now, but it will go on for thousands of years. The parameters that exist today will one day become obsolete. I’m very hopeful that many things will happen, but we cannot even begin to think about them today. Perhaps these things may already exist but we can not yet see their originality. Sometimes we are blind in front of new creations, we only see what looks like what was done before. When we saw Basquiat we said “oh this looks like Cobra” but in the end, the guy was doing his own thing, and you can recognize his work from afar. Today, perhaps something is happening and we don’t see it and something fantastic is going to come out of it. Just like when Picasso did Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) it was a fantastic opening then for Malevich to do what he did and for Mondrian to make those abstract paintings. We just don’t know. I just hope that it’s going to keep moving.

Rail: I’m sure that there is something to what you’re saying, but there is no guarantee that it is moving in a positive direction (whatever that means). There are many different factors relating to how an artist works and how they understand the direction in which they are working?

Venet: Again, if I knew, I would leave you right now and I would go and work on it immediately! It's my only goal! I believe that within the context of my work the period of conceptual art for me, has been a very important period.

Rail: I’ve often advocated a revised sense of connoisseurship whereby those involved professionally in art at least recognize that in addition to painting, sculpture, printmaking, possibly video, Conceptual Art is important. By recognizing that a work of art can be reduced to an idea has both historical and aesthetic validity. This does not mean the end of art. Rather it allows the art aficionado to move aesthetically and intellectually to the next step. You can't live in denial by claiming that something does not exist because you do not believe in it. You don’t have to agree with Conceptual Art, but you cannot deny that it has a certain validity.

Venet: Yes, it exists and it has been extremely influential all around the world. But if I had to choose two artworks that typified my practice, they would be, firstly, a perfect diagram that belongs to Centre Pompidou in Paris of a mathematical equation, and then the collapse we talked about before. I think these are the two best demonstrations of my work. The best of my sculptural work would definitely be the Collapses.

Rail: I agree, but also want to conclude our dialogue by mentioning your recent work, Arc Majeur, on route E411 in Belgium, which was officially inaugurated on October 23, 2019. It’s not an Effondrement, but an extraordinary monumental work that I have seen in photographs and also in earlier versions on the computer. It has been an important work for you over many years.

Venet: 35 years. This is an idea from 1984. Even before, in ’79, I thought about it. I was looking at a small sculpture, you know the typical little arc, one of my very first, and I was thinking “what can I do next?” And I had this vision … well … it’d be great to have a highway passing through it. But then very quickly, thanks to a lot of helpful people, the idea was accepted in 1984. I then made my first photomontages of the highway and the arc around it. So now it is finally there, in Belgium, on the Highway E411, km 99.