ArtSeen

RACKSTRAW DOWNES

On View

Betty Cuningham GalleryApril 3 – May 3, 2014

New York

In Metaphors on Vision, filmmaker Stan Brakhage records a 1963 visit to poet Charles Olson in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the hometown that Olson mined geographically and poetically for the final decades of his life. In a tour of local landmarks, Olson bemoans the loss of “the most beautiful natural spot of these surroundings, not dependent on any man’s concept,” under excavation for a reservoir. The talk turns from landscape to “focus”; Olson emphasizes how cave painters sought out confined passageways, where their eyes were six inches from their subjects—“that feisty little creature, the first perhaps to say, ‘I will have it my way’”—and Olson identifies this creature, who had to “instruct nature” or be eaten, with Brakhage’s artistic persona, which he defines by “narcissism, shyness, and desire to have absolute power over the world.”

These themes evoke the shifting landscapes and artistic myth-making of the 1960s and resonate with the trajectory of Rackstraw Downes, who was then engaged in his own transition from the study of literature at Cambridge to the study of art at Yale. There, he soon abandoned the abstraction of his first teacher, Al Held, for the painterly realism of Fairfield Porter. He went on to engage deeply with man-altered landscapes. He explored organic farming in Maine and painted the parks and built environments of New York, developing the tightly focused realism that distinguishes the 13 paintings now at Betty Cuningham Gallery. These pick up in 1983, with Downes in full command of his resources, and exhibit the range of his subjects and strategies up to the present. The survey coincides with the publication of 29 essays, dating back to 1967, which display Downes’s thorough grounding in art history, literature, and human geography, and which round out the global ambition of his artistic enterprise.

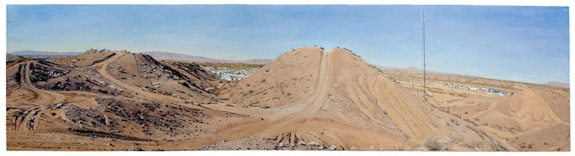

Indebted to the Dutch tradition, Downes has always completed his paintings on site, without use of a camera, but his subjects, and their level of detail, suggest connections to Robert Smithson’s photographic documentation of New Jersey, or to the “New Topographics” photographers identified in a 1975 exhibition. Downes’s work resonates particularly with Robert Adams’s photographs, in their fascination with everyday light. Adams quotes Raoul Coutard, Jean-Luc Godard’s cameraman, who notes that “daylight has an inhuman faculty for always being perfect.” Downes prefers Walt Whitman’s “mere daylight.” “Presidio: In the Sand Hills Looking West with ATV Tracks & Cell Tower” (2012)—the most recent painting at Cuningham and one of Downes’s starkest—recalls Adams’s 1978 photo of a quarried mesa, where sunlight animates barren land with delicate filigrees of vehicle tracks.

But Downes shares other concerns with this group, who revised conventionally framed compositions in response to the enlarged, regularized spaces of highways and subdivisions. Downes himself constructs composite views by adding sheets of paper to his initial drawings, expanding the visual field with multiple viewpoints; these generate the splayed effect of “A Bend in the Hackensack at Jersey City” (1986) or the curving beams of an empty floor of the World Trade Center. The subject-driven character of his compositions has also inspired comparison to the photographs of New Topographers Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Downes bends time as well as space; he speaks of the “tenses of landscape,” the layering of human, natural, and geological interventions. The show includes two four-part works, one depicting attic ventilation ducts at Snug Harbor on Staten Island and another sections of razor wire fence in Brooklyn; in them, multiple views evoke a comprehensive integration of time and space. Elsewhere, circles—the remains of a Texas military cemetery or an open-air dance floor in Presidio—suggest rituals, self-enclosure, a suspension of linear time, or at least its extension in the perceptual durée of painting.

Commentators on the New Topographics have found a sense of detachment and loss in their depersonalized vistas, yet Downes’s effort to bring them into overall focus has more to do with restoration. As philosopher Alva Noë argues in Action in Perception, and as Olson’s stubborn cave painter understands, the visual world isn’t presented to us as a photograph. Nature must be instructed. The uninflected legibility of Downes’s paintings is achieved by sustained visual probing, by what Noë would compare to a process of active touching.

Downes’s landscapes are thus thoroughly seen. Viewers willing to enter them are rewarded not just by subtle painterly effects but also by deeply felt substance. There’s a hard-won visceral quality to the soft delta of weeds and drainage pipes in “At the Confluence of Two Ditches Bordering a Field with Four Radio Towers” (1995), while “Four Spots Along a Razor-Wire Fence” (1999), the show’s most compelling work, suggests latent conflicts, suppressed aggression, and self-laceration.

Downes’s restrained expression is welcome in an age when emotions are often over-exposed and trivialized in social media. His curvilinear compositions in fact have something in common with the late abstractions of his teacher Al Held, with their exaggerated, bowed geometries. Both rejected Abstract Expressionist spontaneity in favor of complex, labor-intensive arts of spatial construction and subdued passion.