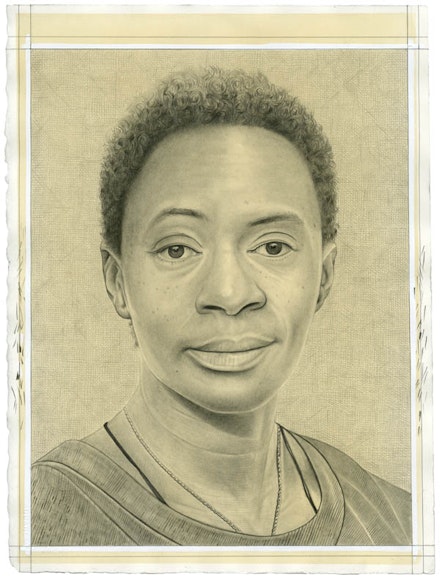

Art In Conversation

A Sonorous Subtlety: KARA WALKER with Kara Rooney

From her all-enveloping cycloramas and iconic wall-mounted silhouettes to her searing films, drawings, and prints, Kara Walker’s work has remained fearlessly stalwart in its condemnation of social and racial injustice. With her most recent project, executed in collaboration with Creative Time, Walker shifts her focus from the cotton plantation of America’s antebellum South to its sickly sweet cousin: the sugar trade. At the behest of Creative Time Kara E. Walker has confected: A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant opens to the public on May 10th, and, as its title suggests, avows to be anything but ordinary. Earlier this month, Walker took the time out of her schedule to speak with Rail Managing Art Editor Kara Rooney about her hopes for the installation as well as its complex socio-political implications.

Kara Rooney (Rail): The executionary details of this project were largely developed in secret, so that very few of us in the press are aware of what the final iteration will look like. Can you describe what viewers will encounter when they finally walk into the space on May 10th?

Kara Walker: I hate talking about it. The great thing about having a secret is that it just stays a secret.

Rail: In that case, let’s start with narrative, since that’s historically played such a significant role in your work. How did the story of the sugar trade influence your decisions on both a formal and intellectual level for this project?

Walker: It started with thinking about the space. I was approached by Creative Time a while back, maybe a year ago, about working with the Domino Sugar plant. One of the selling points for me was the plant itself, along with this amazing history of sugar and its attendant legacies of slavery. There are decades of molasses that cover the entire space; it’s coated—it’s an amazing relic or repository vessel that contains all of these histories, and so the venue is actually doing a good portion of the work. I began to think about how to arrive at a piece, given the work that I’ve done in the past, which has been primarily two-dimensional, and even with film and video thrown in, is large, but not this large. So I started with a lot of sketches; each sketch went from very minimal gestures to this maximal output with all kinds of moving parts. It came to embody something I would never want to see, something that was about slavery and industry and sugar and fat and wastelessness. It was a kind of finger-wagging gloom-and-doom kind of sketch that embodied all of the themes about industrialization that the space contains: post-industrial America, the grandiose gesture of the industrialists, and sugar as the first kind of agro-business.

For example, you can’t get sugar without heavy-duty processing; you don’t get refined sugar, you get other things. This desire for refined sugar and what it means to turn sugar from brown to white and how that dovetails into becoming an American were fascinating to me. Sugar is loaded with meaning, with stories about meaning.

Rail: What were some of your resources in looking into the history of the sugar trade and Domino’s role in particular?

Walker: There is a passage in a book by Sidney Mintz called Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1985), where the author talks about the Middle Ages in Europe and England and how sugar there was a highly prized, expensive commodity.

Rail: It was for the aristocracy.

Walker: Yes. Sugar was rare, even considered medicinal. It was like gold, extremely precious. At a certain point coming from the East in the 11th century, there began an enormous effort, at the bequest of the sultans, to make these strange, grandiose marzipan structures. Once they were fashioned, they would present and give them to the poor on feast days. This tradition made its way to Northern Europe where the royal chefs began making similar sugar sculptures. The thing that really struck me about these sugar sculptures was what they were called—subtleties—there it is. [Laughs]. They were intended to represent the power of the king, not just in their being made of this prized commodity, but also in their representation of the signing of a treaty, or the hunt. So you had these sugar sculptures of the deer and the king, and there would be some kind of oratory or maybe a little poem that would be said, and then everybody would eat them. They would be presented between meals as this beautiful, edible trophy. It was after reading this that I realized I had to make a sugar sculpture and a large one. So that answers the first part of your question: the sugar sculpture. She is basically a New World sphinx. A New World thinking of the sugar plantations, the Americas, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, that sort of Rolling Stones-y brown sugar dovetailing of sex and slavery as it reaches the American imagination.

Rail: Does this New World sphinx—what sounds like a veritable femme-fatale—relate in any way to the black feminist literature that emerged in the ’70s, initiated by Alice Walker, for example, or is it something more visceral and personal?

Walker: Something more personal, definitely. I think the scale of the piece will probably embrace and eclipse almost anything that you bring to it. [Laughs.] We have 80 tons of sugar in this structure, which measures approximately 80-feet long by 40-feet high, so it doesn’t occupy the entire space but it does occupy it in a very specific way. She also has some sugar candy attendants who are about a third of this in scale.

Rail: What is their origin?

Walker: They are actually taken from 10-inch tall tchotchkes that I bought on Amazon—little black slave boys carrying baskets and presenting different things. They’re very goofy.

Rail: How has working with sugar as a medium challenged the way you approach themes such as white fears of black potency, violence, shame, and resistance? Is the transmission of these ideas still as direct for you as it has been with the cut silhouettes, drawings, and films?

Walker: It’s so much better, honestly! No, I don’t know if it’s better. I like the cutting paper thing, but—maybe it’s simply because it’s something that I’m doing that it feels similar, because it’s my own body. There is a similarity in working with cheap materials. [Laughs.] The cheapest materials available. They’re both temporal, ethereal materials to work with, very finicky. It feels cathartic in the way that working with silhouettes was for me coming from painting. There is a similar kind of movement into another set of dimensionality and scale. I am moving my body around it in a way that’s very new and exciting. The sugar itself is really just a paste, just sugar and a liquid. Once these components are mixed you have something that you can model and play with. Then, depending on whether you’re using heat or not, you get different properties, wildly different properties.

Rail: So this sticky sweetness of the 18th-century silhouette, and the craft tradition that goes along with that, has translated for you in a very physical way.

Walker: I think so, and even in a literal way. We’re literally sugarcoating history. [Laughs.] There are two different things that I’m doing with the sugar and those are what I need to clarify. The main object, the sphinx, is sugarcoated; the smaller objects—these servant figures, or procession of servants—are basically just like big lollipops. Those have been very problematic to work with. We’ve got these molds and they’re solid but we’ll see if they hold up. The first one just collapsed. It was really terrible at the same time that it was kind of awesome to look at because it became this pile of beautiful, caramelized amber. It’s such a fragile and volatile substance that doesn’t like to take on too many forms, which is fine. I keep trying to tell everyone that I’m not a stickler for conformity, so if each one is wildly different, then that’s their attempt at freedom I guess.

Rail: What color are they exactly?

Walker: They’re different colors. At the moment the one that is standing is mostly brown. He burned. He went from caramelized to burnt so he’s a little marbleized, really dark. The first one came out a beautiful amber color. Like when you see caramelized sugar drizzled on your plate, he was that color, but like I said, too soft.

Rail: And the larger sculpture is amber as well?

Walker: The sphinx is white, bright white.

Rail: The element of color is something that I want to discuss. With the silhouettes, the color black is inherent to the 18th-century art form you employ, whereas with sugar there is a transfigurative chemical process that must take place in order for it to become the white powder with which we are all familiar. In a sense, the silhouettes require little conscious agency on your part in order to elicit the desired references. But with these pieces, an additional step is necessary in order to enact that same physical transformation. How did this reverse process of moving from dark to light, a natural to an artificial state, resonate with you? For example, why did you decide to make the sphinx this gleaming white as opposed to brown, or even black?

Walker: I had my options: brown and white. I was thinking about all the products of sugar—molasses, brown sugar, natural sugar, and refined white sugar. I was experimenting with these different kinds of sugar, cooking at home, making all types of different candies, testing different boiling points, then just dumping it out and seeing what would happen. The white against the molasses of the walls of the interior of the refinery will be visually striking. I was also thinking about the fact that I am in a black interior. The plant is not a white-box situation. The project presented an opportunity to invert this paradigm and maybe call into question the desire for the refined—to ask what is lost in the process of refining. This is a testament and monument to the quest for whiteness, the quest for whatever that means. Authority—even as it’s presenting itself on its last legs—this ideal of mastery over continents, people, bodies, ecology. Yes, the sphinx is inverted in multiple ways. But part of it was really part of a visual oooh-factor. The way the light comes in, what the sugar looks like when it has been crystalized in a certain way. It’s a little bit crazy actually. Crazier than you imagine it. [Laughs.]

Rail: With the silhouettes, you’ve said that the minimal formalism of the cartoon profiles resonated with your idea of racial stereotypes, functioning as reductionist versions of actual human beings. With three-dimensional sculptures, this flattening of identities is disrupted. How did you contend with this dimensional shift?

Walker: Physically, it is a shift, but there’s something that resonates between those works and this work. I would not have thought, “this is the same as the silhouette,” but it does feel like it kind of operates in a similar way—it sets up an expectation in the viewer and then starts to complicate that expectation over the course of the viewing. With the three-dimensional shape, and specifically this sphinx-like one, the work becomes iconic, hugely iconic; it does the same thing in the way that the silhouette stereotype figures do. It transcends humanity in the way these other forms reduce humanity. So it’s larger than life, a set of representations that can’t be fully embraced all at once.

One aspect of the process that is different, however, is that I can’t be as hands on. For example, I’m not there now. I was there yesterday working on it along with a team of people and fabricators. It’s a way of working that I’m not used to.

Rail: You typically fabricate all of your work by hand, correct?

Walker: Yes. After the fact there’s often fabrication that happens because of the archival needs of the paper works, but that’s usually after the work has already been created.

Rail: What has that letting go process been like for you?

Walker: It’s a little weird. I feel very contrite when I’m around the folks who are working. Contrite and thankful, they’re doing a wonderful job translating my sketches, notes, and drawings and such.

Rail: The significance of titles seems critical to your output, usually appearing as very long and narratively descriptive. The title for this particular installation is similarly lengthy. How does this mode of naming serve your work?

Walker: In this case it’s kind of funny because the whole thing is so theatrical. In the gallery setting I like to play with the idea that we’re not entering into a dialogue with modernism or even, necessarily, with art. Rather, we’re entering into my universe, whether you like it or not. It’s kind of a coercion into liking it. There have been a few moments where I try to be subtler with my titles for a show, but it has felt like a weird capitulation or some demand for an austere, protestant kind of approach to good art or taste. So, yes, my titles are theatrical or maybe a little overbearing or hyped up. The idea of the artist as a kind of truth-teller is sort of hilarious, so why not go with it?

Rail: So they’re meant to be simultaneously theatrical and a way for you to re-write history?

Walker: Or to claim it, along with my own agency within the gallery setting—to maybe, for a moment, wrest control away from the white box or something.

Rail: They do leave little room for interpretation on the part of the viewer. I’m wondering if this type of, for lack of a better word, heavy-handedness is something you feel is necessary if we are to redirect our gaze effectively?

Walker: You think they’re heavy-handed? I think they’re hilarious.

Rail: I think they can be both. That’s what is so brilliant about the way they inform the work. They don’t back down.

Walker: They are bombastic, yes. There is a little bit of voodoo attached to it, I guess. By assuming authority over my own work I might actually have some authority over my own work, and I might actually convince the viewer that that, in fact, is true! It seems to work [laughs], although even I don’t always buy it.

Rail: You’ve spoken about the influence Adrian Piper had on your work as a younger artist. In light of your emphasis on titling and the way you’ve used text overall, I’m particularly interested in how her relationship to language has affected yours.

Walker: I guess the influence would be in my thinking about addressing the “other,” the other being the viewer or the objectifier of my work or my body. Sometimes you forget that it’s not all in your head and that viewers of your body and viewers of your artwork are objectifying and limiting, creating alternate realities and alternate narratives for you to reject. Piper’s work has been important for me in trying to understand or recognize what the relationship is that I have with myself as a subject and object.

Rail: Censorship is still a very present issue for you. Even almost 15 years after having received the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant and the controversy that surrounded that award, as recently as 2012, a drawing of yours was temporarily banned from display at the Newark Public Library. It was shocking for me to think that in a community whose demographic is largely African American this imagery might be deemed too “racy” for the population. Since the Domino plant is also a public space that places you again in the position of addressing a non-artworld audience, was this something you had to consider as you developed the project?

Walker: Yes, this is a point of conversation we are having now. It may be an issue, and maybe it’s the representation of women that becomes the issue, maybe it’s the features on her face—her representation of blackness—is she iconic? Is she stereotypical? Is the figure strong? Is she debilitating? But as far as potential controversy, I don’t know what will happen with this piece. I’m not strategically thinking about these sorts of things when I work, but the imagery does come from my own sensibilities, my own ways of moving through the world. It has my own mixed-up sense of humor in it that is really present, the same type of humor that was embodied in the drawing displayed in New Jersey. I felt good about that work, and then it disappeared to who knows where before it turned up in the library in Newark. At the same time, in the way the conversation and controversy surrounding that event evolved, it presented an opportunity for me to be an educator.

I’m not there to convert people into loving my art, but to explain that there is a process. Because sometimes for viewers—especially those who don’t have a lot of exposure to the arts—art just comes at them; it’s just there and there is no explanation. There is no understanding that along with this presentation comes a definite process, that there is an individual behind it. There are aspects of the museum and gallery world that are problematic for viewers, in that there isn’t an opportunity to answer back. Or you have to utilize these staid forms such as a panel discussion or an artist talk. In light of this, what should a viewer do if they’re upset or moved? Are you supposed to just hold it in, or do you react? There is something about the call and response of other aspects in the black community—in the black church, in music, in dance—where there is a way of activating the art so that it is alive and living and not this dead thing on a wall that you walk away from, that you feel or don’t feel or are terrorized by.

Rail: It reminds me, to a certain extent, of the controversy surrounding Robert Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio in the early ’90s, and how the institutions that exhibited the work took the stance of aestheticized distance as a response—looking at the imagery and the idea of the other through a purely formal lens. Thankfully, you had art critics like Dave Hickey who rejected this viewpoint saying, “No, this is a cop-out. These images are supposed to be provocative, they’re meant to provoke. They’re meant to be dangerous and seductive and sexy.” So in that sense, I think that piece really did do something. There probably wouldn’t have been an occasion for discussion there otherwise. It means that your work has agency in the world.

Walker: I’d like to think so.

Rail: I want to return to the subject of the Domino Sugar Factory itself because it is such a loaded place; loaded with industrial history as well as a turbulent one of racial and class struggle. The original refinery was built in 1882. By the 1890s it was producing more than half of the sugar in the United States. So it is not only an iconic landmark in terms of its architectural façade, but served as a locus of activity and consumption in America for more than 100 years.

Even in the latter 19th century, after sugar was no longer grown and processed by a slave population, the plant continued to have an ongoing association with minimal wage earnings and extreme poverty. As recently as 2000, it functioned as the site of one of New York City’s longest labor strikes, with over 250 workers protesting wages and working conditions for 20 months.

Walker: Which didn’t turn out well.

Rail: Right. When you walk into a space like that, when you know this information, this factual history, how does that affect your vision for the space? How does the building itself influence the objects you create in response to it?

Walker: It messes with them. It messes with the space, or rather, it messes with the histories, which I always do too. [Pauses.] Imagine gathering all the sugar in the world in one location. This demands immense amounts of physical labor, from the Dominican Republic to Cuba and other sugar islands, that brought that product onto that site, and are still bringing that product onto the other site in Yonkers. Then there’s this insane amount of pressure, heat, centrifugal force, and manpower necessary to bleach the sugar. Not to bleach it, exactly, but to turn it from its natural brown to white state. There is all this knowledge that comes with that, the learned knowledge of the men and women who have worked on this site for years and years and years, not to mention of the families of these laborers. There is a living memory of the smell and the steam—this heavy molasses odor that’s still in the space.

Rail: It’s like the gooey, sticky manifestation of America’s original sin.

Walker: Yes. There’s this grassy, pungent, almost nauseating sugar smell that lives in the tissue of everyone who has worked in that plant. I wasn’t aiming to depict an accurate representation of labor, but to evoke the associated ideas of empire, of the past—their relics and ruins; you’re always cognizant of those mythical humans, for example, who built the Pyramids of Giza. There is this awe and wonder that goes hand-in-hand with these places but it’s without the thoughts of the sweat and labor behind it. I wanted to make something that would contain that sweat and labor in the histories of the totality of sugar production—the here and now and the past and present of it—but that would also elicit this terribly sad memory of all that’s lost. It’s colossal and at the same time temporary, made from something completely vulnerable to the elements and time. Hopefully that awesomeness will also be there.

Rail: My last question, which you just touched upon, circles back to this issue of class that’s raised in the setting of this work. Given the building’s future fate and the rampant gentrification currently taking place throughout New York, coupled with the fact that sections of the plant are already being dismantled for what is slated to be the largest residential construction on the Brooklyn waterfront, what are your thoughts on how this space’s identities as a historic site of racial and class warfare and its future trajectory as luxury condos coalesce or diverge from one another? [It should be noted that 700 of these units have been slated for low-income housing, but that represents a mere 30 percent of the overall construction.]

Walker: I don’t know if I have a satisfying set of answers to that question. When I think about the space, and even before I was working in it, I recognized it as emblematic of the kind of shortsighted progress—the entrepreneurial, industrial, moneyed, ever forward, ever onward, no matter what, no matter who gets hurt—that has taken hold of the city.

I am an agent of tricksterism, and I knew I could use that. In order to bring myself to build something as heroic and herculean as this effort, I had to get into that mindset of industrial conquest. Now, whether or not the builders who are behind some of this project will get that, I can’t be sure. And I don’t know what that says to the people who are left high and dry by this constant moving, constant gentrification, constant building. I’m in a really tricky position because with this project, I wound up being both the beneficiary and the hand-biter. I have lived in the city for 12 years now and the work never seems to be done; the city is constantly pushing people out. I don’t know where everyone goes. Struggling, striving, there is a weird engine in the city that is constantly being fomented. The question that arises with the waterfront there is if we reach the pinnacle of condo building, when does it stop? When do we make space for everybody else?

Rail: And how do we make a stand against that? I imagine this project is one way of doing so.

Walker: I don’t know, do you think? I don’t know if this piece will do that. My feeling is—and this is a kind of pipe-dream poetic feeling—of the piece being present, and the piece disappearing. My greatest hope is that when all is said and done that the aftereffect is still there. That it’s not just another lost memory, like the lost memories and collective knowledge of the people who worked at the sugar factory. [Sighs.]