Historical Origins

Situated Cognition draws its ideas from anthropology, critical discourse analysis, critical theory, philosophy, and sociology. In the late 1980’s, Browns, Collins, and Duguid developed situated cognition, which is also known as situated learning theory. This theory puts an importance on educators to teach students concepts in contexts that can be applied in the real world. In the early 1990’s, social cognitive anthropologists, Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, discussed the notions around the communities of practice and collaborative learning. Both groups of researchers have evolved their ideas from each other. The ideas surrounding situated cognition can be seen today around the concept of “21st Century Learning.” In the past, there have been many questions revolving around how the brain functions, how knowledge is related to culture, how animals think differently compared to humans and etc. Over the past century, researchers reviewed one another’s work within the scope of artificial intelligence, neurobiology, anthropology and ethology (Clancey, 1997). As a result, they have come up with an approach, called situated cognition, which stresses on the roles of feedback, emergence, and mutual organization in intelligent behaviour (Clancey, 1997).

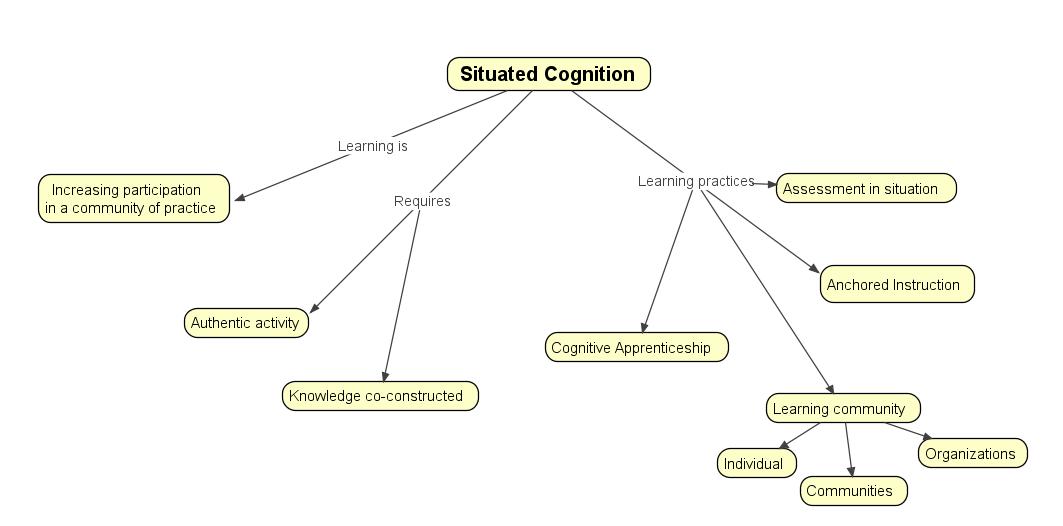

Summary and Core Concepts

Kirshner and Whitson (1997) stated that cognition is believed to be created through activities that are both social and situated in nature, where one learns through mimicking what experts do (as cited in Driscoll, 2005). A person who advocates situated learning would argue that if contexts of knowing and doing were taught separately then it will lead to inert knowledge (Driscoll, 2005).

Clancey (1997) claims that the nature of situated cognition is based on the notion that every human thought made is tailored to the surrounding environment. The way one perceives, the way one visualizes their activities, and their physical acts are all developed together (as cited in Driscoll, 2005).

Furthermore, the situated cognition theory is based on a sociocultural setting over an individual setting. Driscoll (2005) states that “knowledge accrues, through the lived practices of the people in a society” (p. 158). In most theories, the relation between the social aspect and the individual aspect must be understood from knowledge lived practices (Driscoll, 2005).

Lave and Wenger (1991) discuss learning as participation in communities of practice, where learning as participation has its focus on the ways relationships evolve and continue to extend among people, their actions and the world (as cited in Driscoll, 2005). Learning as participation in communities of practice involves one’s participation in multiple communities of practice and an identity is created within each community through personal participation and development (Driscoll, 2005). Furthermore, Wenger (1998) states that learning as participation does not only shape our performance or things we do but also identifies who we are and recognizes how we do things (as cited in Driscoll, 2005).

As Driscoll discusses about the antecedents of the Situated Cognition Theory, he brings up the argument that Brown et al. has raised, where Brown et al. believed that many traditional teaching methods led to inert knowledge because students lacked the ability to link what they have learned to the situations that they have experienced. Students who just performed rote memorization on what they have learned would find it difficult to solve problems that are more complex and related to real-world scenarios (Driscoll, 2005).

Further in Driscoll’s article, he discusses J.J. Gibson’s ecological psychology of perception. J.J. Gibson was a psychologist who proposed that the heart of ecological psychology is to see the relationship between the behaviours that organisms have in relation to their environment. The term affordance was used in defining how the environment plays a role in an organism’s behaviour (Driscoll, 2005). One example highlighted in the article involved a cockroach and a piano. For a cockroach, a piano is a stable and great home for nesting. In other words, the piano affords cockroach a great home. However, for music students, the piano affords music to be played just like how the keys of the piano afford sound to be created. Hence, the piano is perceived differently under different environments and is believed to afford different behaviours (Driscoll, 2005).

Similar to Clancey’s beliefs, Driscoll (2005) argues that people should not just be interacting with the physical properties in their environment; instead they should be interacting with the concepts that were constructed by themselves as well. Driscoll also stresses the importance of critical pedagogy and its relation to multicultural learning, as proposed by Damarin (1993), who believed that the sharing of one’s language, norms and histories will help learners feel contended in their knowledge communities (as cited in Driscoll, 2005). Furthermore, Driscoll argues for Rogoff’s point that there are students who may perform poorly on an exam on one subject but yet be able to resolve problems in the same subject in their everyday life (Driscoll, 2005). In 1984, Rogoff stated that everyday thinking “is not illogical and sloppy by instead is sensible and effective in handling the practical problems” (as cited in Driscoll, 2005, P. 164).

Later in the article, Driscoll examines the process of Situated Cognition. Lave and Wenger (1991) defined legitimate peripheral participation to be the belonging means to a community of practice (as cited in Driscoll, 2005). Wenger (1998) visualizes learning as participation in three levels:

1. For individuals – a member that participates and learns within the community of

practice

2. For communities – improves the practice of the community and welcomes new comers

3. For organizations –an organization being effective through nourishing and supporting

the interconnected communities of practice.

In order to look at legitimate peripheral participation, cases based on apprenticeship have been examined. Lave and Wenger (1991) emphasize that the role of apprentice learning is to have a master to provide tasks to an apprentice and, as the apprentice becomes more competent, the master will assign more responsibilities (as cited in Driscoll, 2005). Apprenticeship learning promotes strong goals and motivations to its learners; hence the learners are more engaged in their practices and have a better vision of the project. Further, apprenticeship learning allows peer-to-peer support that makes learning more effective as well (Driscoll, 2005).

Additional legitimate peripheral participation that Wenger proposed includes:

- Peripheral

- Inbound

- Insider

- Boundary

- Outbound

Driscoll then explores cognition as semiosis in his article, Whitson (1997) defined semiosis as “the continuously dynamic and productive activity of signs” (as cited in Driscoll, 2005, P. 170). A sign can be viewed as a representative of an object or the foundation of a metaphor or analogy under certain situations (Driscoll, 2005).

Near the end of the article, Driscoll (2005) discusses a problem-based approach proposed by the Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt (CTGV). Their method of anchored instruction is an example of problem-based learning that uses an interesting situation as an anchor to focus the learning goals. Overall, the intention of anchored instruction is to have learners develop useful knowledge rather than inert knowledge.

Problem-Based Learning Video

The animated paper-cut video below explains Problem-based Learning and the steps involved in the learning process.

What is PBL? from Metafoormedia on Vimeo.

Key Definitions

Problem-based learning: A learning approach where students are provided with realistic problems that don’t necessarily have right or wrong answers.

Anchored Instruction: A problem-based learning method that utilizes an interesting situation as an anchor for learning.

Community of Practice: A social situation where ideas are judged useful or true.

Legitimate Peripheral Participation: Genuine involvement in the work of the group, even if one’s abilities are undeveloped and their contributions are small.

Situated learning: The kind of learning in which skills and knowledge are tied to the situation in which they were learned and difficult to apply in new settings.

References:

Brown, Collins, & Duguid (1989). Situated Cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18, 32-42. Retrieved October 21, 2011, from: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0013-189X%28198901%2F02%2918%3A1%3C32%3ASCATCO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2

Clancey, W. J. (1997). Situated cognition: On human knowledge and computer representations. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Driscoll. M.P. (2005). Psychology of Learning for Instruction (pp. 153-182; Ch. 5 – Situated Cognition). Toronto, ON: Pearson.

Visual Credits:

Wordle. (2010). Retrieved October, 25, 2011, from http://anchoredinstruction.wordpress.com/2010/07/13/theory-features-strengths-and-weaknesses/

Video Credits:

Metafoormedia: What is PBL? [Video file]. Retrieved October 31, 2011, from http://vimeo.com/13097388