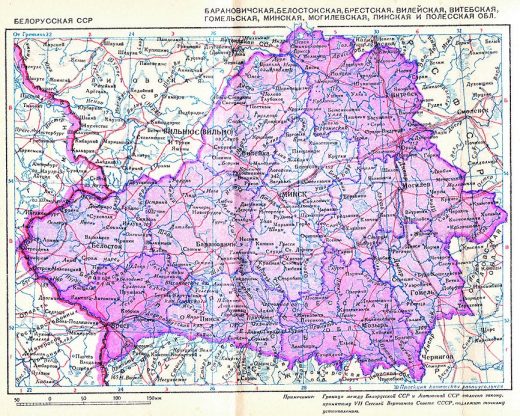

Map of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940.

Reviews Understanding the geography of Belarus 95 maps with comments

Belarus in Maps, Edited by Dávid Karácsonyi, Károly Kocsis, and Zsolt Bottlik. Budapest: Geographical Institute, 2017, 194 pages.

Published in the printed edition of Baltic Worlds BW 2019:1. Vol. XII. pp 73-74

Published on balticworlds.com on March 26, 2019

Belarus in Maps is an important contribution to the study of the geography, history, and contemporary development of Belarus and is a result of an international research project based at the Geographical Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The project was initiated in 2005 by Prof Károly Kocsis and has been developed in cooperation with the Faculty of Geography at the Belarusian State University in Minsk and the Institute for Nature Management at the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus.

The book is a part of the “In Maps” atlas series published by the Geographical Institute in order to introduce countries of Eastern Europe to the wider English-speaking world. Among the previously printed volumes are South Eastern Europe in Maps (2005, 2007), Ukraine in Maps (2008), and Hungary in Maps (2009, 2011). The aim of the series is to offer complex geographic, socio-economic, cultural, demographic, and historical perspectives on the Eastern European countries and their region.1

The book is composed of nine chapters, an introduction, and appendixes, and it is richly illustrated with 95 maps, 10 tables, and many pictures.

In chapter one — Belarus in Europe — the authors turn their attention to the role of Belarus in European history. The authors define Belarus as “a gateway between the Europe and Russia” (p. 19). The history of Belarusian statehood is presented on pp. 20—28. Regarding the use of different names of the country in English (Belarus, Byelorussia, and White Russia), the authors explain that the correct name of the country is Belarus, which is not related historically to Russia, but to Kievan Rus — an early medieval state with its center in Kiev (today’s Ukraine). This is a strong historical argument for using the name Belarus in other European languages, for example, in Swedish that still officially uses the name Vitryssland (literally White Russia), while its largest morning daily, Dagens Nyheter, rather recently decided to use Belarus.

The authors provide insight into the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the full name of the state is the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia, and Samogitia) and stress the role of the Grand Duchy in the formation of the Belarusian people. Indeed, the borders of the Grand Duchy with Poland and Russia almost perfectly coincide with the ethnic borders between Belarusians and Russians in the east, Belarusians and Poles in the west, and Belarusians and Ukrainians (who during medieval times were subjects of the Polish Crown) in the south. A special part of the first chapter is devoted to the history of Jews in Belarus. The authors provide a detailed map titled The Pale of Settlement (fig. 14) and mark the unique role of Belarus in the development of Jewish culture. The authors point out that prior to World War II Soviet Belarus had four official languages — Belarusian, Yiddish, Polish, and Russian. Actually, Belarus was the first republic in the modern world that gave the Jewish language an official status. The Nazi genocide of the Jews in Belarus is presented on pp. 26—27, but no map on the Holocaust in Belarus is provided.

Unfortunately, the authors have ignored many important publications in English on the history of Belarusian statehood,2 and this has led to some errors. For example, on p. 20 the authors point out that during the Nazi occupation (1941—44) the western (prior to 1939, Polish) area of Belarus formed a part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland, while the southern areas of Belarus were included in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. In fact, the administrative composition of Belarus during the German occupation was much more complicated, and the territory of Belarus was divided into four occupied zones. The largest part, which included the former Polish territories and the central area of the Belarusian SSR with its capital Minsk formed the general district of Belarus (Generalbezirk Weissruthenien, then a part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland). The southern part of Belarus was administrated in 1941—44 by the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, but in March 1944 it was transferred to the Generalbezirk Weissruthenien. The Hrodna and Białystok regions of the Belarusian SSR were incorporated into the Third Reich. The eastern part of Belarus was under the military administration of the Wehrmacht. The administrative rules and the dynamics of the mass killings were different in the different occupation zones.3

The authors conclude correctly in chapter one that the present-day borders of Belarus were established in 1919—45. Indeed, in August 1945 the Białystok region and three districts of the Brest region (a part of Soviet Belarus in 1939—41 and in 1944—45) were transferred back to Poland. Therefore, Belarus was one of the few countries in Europe that fought against the Nazis but lost part of their territory after 1945. Moreover, some small territorial exchanges between the Belarusian SSR and Poland and between the Belarusian SSR and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic took place in 1950 and in 1964. These boundaries were inherited by the Republic of Belarus after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. (As a pure curiosity, the insignificant and today uninhabited exclave Medvezhye-Sankovo [Russian: Medvezh’ye-San’kovo] of the Russian Federation, situated east of Homiel [Gomel], is not mentioned.)

In the second chapter, the authors examine more precisely the historical, cultural, and ethnic roots of Belarus. They pay special attention to the religious and cultural diversity of Belarus and the role of the Orthodox, Greek-Catholic, and Roman-Catholic churches as well as the Reformation in the development of Bela-rusian identity (pp. 43—50). Unlike ethnic Russians, the ethnic Belarusians since early modern times have been adherents of various religious denominations. The religious diversity of the population resulted in the coexistence in Belarus of different cultures and different written languages (including Belarusian, Russian, Polish, Latin, and Church-Slavonic). After the fall of the Soviet Union, most of the historical churches were re-established in Belarus that today is one of the most multi-confessional countries in Eastern Europe. Like in Norway, the cultural diversity of Belarus has resulted in two grammars of Belarusian literary language (the so called taraskievica and narkomauka) and in a mixed spoken dialect — trasianka (a mixed language of Belarusian and Russian) — that is used in rural areas of Belarus.

Hungary has a long tradition in cartography, and the quality of the maps is exemplary. As usual, the spatial representation of societal, economic, and demographic characteristics tends to overemphasize rural distributions in relation to greater, but more concentrated, ones, but the cartographers use proportional circles as well as vectors and diagrams that are all easy to understand and in perfect coloring. In a very useful appendix, important place names are given in five different versions, including Belarusian and Russian and in Cyrillic and Latin letters.

Very few academic works have been published on the historical and cultural geography of Belarus in English.4 Therefore, despite a few minor critical points, the atlas-book Belarus in Maps has considerable importance for understanding the geography, history, and contemporary development of Belarus.≈

References

1

About The in Maps atlas series, http://www.mtafki.hu/inmaps, accessed January 25, 2018.

2

See: Vakar, Nicholas, Belorussia: the making of a nation: a case study, Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1956; Snyder, Timothy, The reconstruction of nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569—1999, (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003); Kotljarchuk, Andrej, “The tradition of Belarusian Statehood: a war for the past”, Contemporary Change in Belarus. Baltic and Eastern European Studies. Vol. 2. (Södertörn University College. 2004), 41—72; Rudling, Per Anders, The rise and fall of Belarusian nationalism, (1906—1931, Pittsburgh, PA), 2015.

3

Kotljarchuk, Andrej, ”Nazi Genocide of Roma in Belarus and Ukraine: the significance of census data and census takers” in: Etudes Tsiganes, 56—57 (2016), 194—217.

4

For a few examples see: Loiseaux, Olivier & Section of Geography and Map Libraries (red.), World Directory of Map Collections, 4th Edition, (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2000); Kotljarchuk, Andrej and Viktor Temushev, a map “Grand Duchy of Lithuania and its administrative, geographical and religious divisions”, in: Kotljarchuk, Andrej, In the Shadows of Poland and Russia: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Sweden in the European Crisis of the mid-17th Century (Södertörn University, 2006), online: http://sh.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:16352/FULLTEXT01.pdf , accessed January 25, 2018.

Issue 2024, 1-2:

Issue 2024, 1-2: