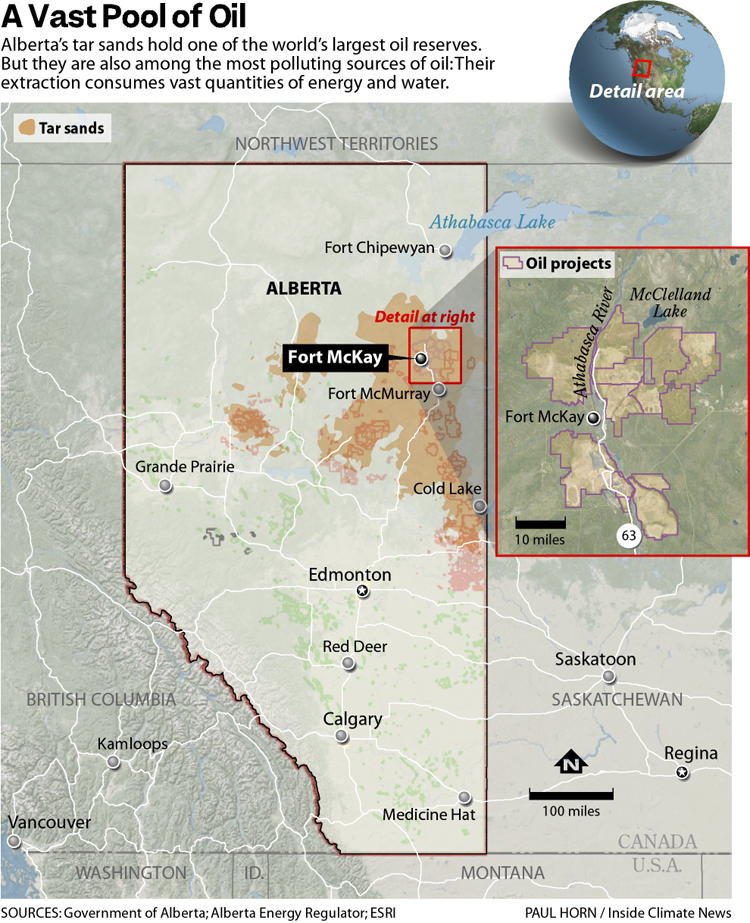

Canada’s oil sands stretch across a large area of northern Alberta and are one of the world’s largest deposits of crude. Canada is the biggest source of oil imports to the United States and most of that petroleum comes from the oil sands.

The deposits do not technically hold crude oil, but instead a heavier hydrocarbon called bitumen, which must be heated and treated in order to form a liquid that can be piped and refined like oil. That process requires sprawling industrial operations of open pit mines, ever-growing waste ponds and refinery-like “upgraders.” The waste ponds have leached toxic chemicals into groundwater, and a heavy, sulfurous stench often settles over the region. The mines have stripped away an area larger than New York City, lands that had long been occupied by people from several Indigenous First Nations. One of those First Nations, Fort McKay, is now surrounded by mines.

Jean L’Hommecourt, an enrolled member of the Fort McKay First Nation who has fought to clean up tar sands operations for years, said she wasn’t surprised by the new study’s findings.

“I was just like, eh, I knew all along,” L’Hommecourt said. She helped the nation set up its own air quality monitoring years ago when it suspected health impacts from the mines. “We feel the physical effects here,” she said.

Some bitumen is extracted using a system of wells that inject steam to effectively melt the hydrocarbons underground before pumping them to the surface, known as “in-situ” extraction.

The study found that both types of extraction released comparable levels of air pollutants relative to their size.

The study emerged from earlier work, published in 2016 by some of the same researchers, which found high levels of particulate pollution downwind of the oil sands. That study left the question of what exactly was being emitted by the mines to form these particulates, Liggio said, and whether those emissions could explain that downwind pollution.

“The short answer to that question is yes,” Liggio said.

Liggio said the findings suggest that scientists and regulators do not have a proper understanding of air pollution across the region. Because it is impractical to measure all pollutants across large areas, he said, regulators often rely on modeling to estimate air quality. The models rely on inventories different industries use to report their emissions, and “you need to get the inputs into that model correct,” Liggio said. “What we’re showing here is that the emissions are not fully correct, they’re higher than what’s currently in the inventories, which by extension means that if you’re trying to model the impacts, the exposure, et cetera, you’re probably not going to get that right either.”

The paper did not try to assess the health impacts of the pollution it measured. But Liggio said the findings could have implications beyond the region. The organic compounds the researchers measured tend to linger in the air for only a day or less, he said. But the most surprising finding was that there were much higher levels of heavy organic compounds, which are much more likely to react in the atmosphere and form particulate matter. Once formed, those particles can then hang in the air for weeks and travel hundreds or thousands of miles—they are the same type of pollutants that Canadian wildfires sent across the continent last summer, blanketing cities in the eastern United States.

The paper also raised questions about methods for disposing of the toxic “tailings” that are left over after extracting bitumen from the mines. This solid waste has been accumulating in water-filled lagoons, which by 2020 had swelled to cover an area nearly twice the size of Manhattan. Remediating these pits has proven to be extremely difficult, and laboratory tests conducted by Liggio and the researchers suggest that some novel efforts for separating solids from liquids could release even more pollution-forming compounds into the air.

Nicholas Kusnetz is a reporter for Inside Climate News. Before joining ICN, he worked at the Center for Public Integrity and ProPublica. His work has won numerous awards, including from the Society of Environmental Journalists, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Society of American Business Editors and Writers, and has appeared in more than a dozen publications, including The Washington Post, Businessweek, The Nation, Fast Company and The New York Times.

This story originally appeared on Inside Climate News.

reader comments

248