Artist will live forever! claimed the painter and one of the best draftsman of all time, Austrian painter Egon Schiele (1890-1918). No, artists will not live forever, but their works will. However, the problem is when artists die young, at 28, as Schiele. It’s a pity. It is inevitable to wonder how his work would have evolved, what life would this man have led, a young man who lived his short life so intensely, a man fragile and confident at the same time. Crazy or too much lucid, always controversial. Picture above: Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912). Leopold Museum, Viena)

Heroes die young, mythology tells us, because they have performed their feats beyond human limits, they have given everything too soon, without pauses and without any rest. Is it a romantic point of view? Throughout the history of painting, painters that have died too soon it was due to a poor health, for catching diseases that could not be cured then, wars, bad habits or simply bad luck. Toulouse Lautrec, Van Gogh, Raphael, Hishida Shunso died at 37, Modigliani, Franz Marc and Moira Dryer at 36, Robert Smithson at 35, Umberto Boccioni at 34, Giorgione at 33, George Seurat and Keith Haring at 32, Jean Michel Basquiat at 28, Aubrey Breadsley at 26.

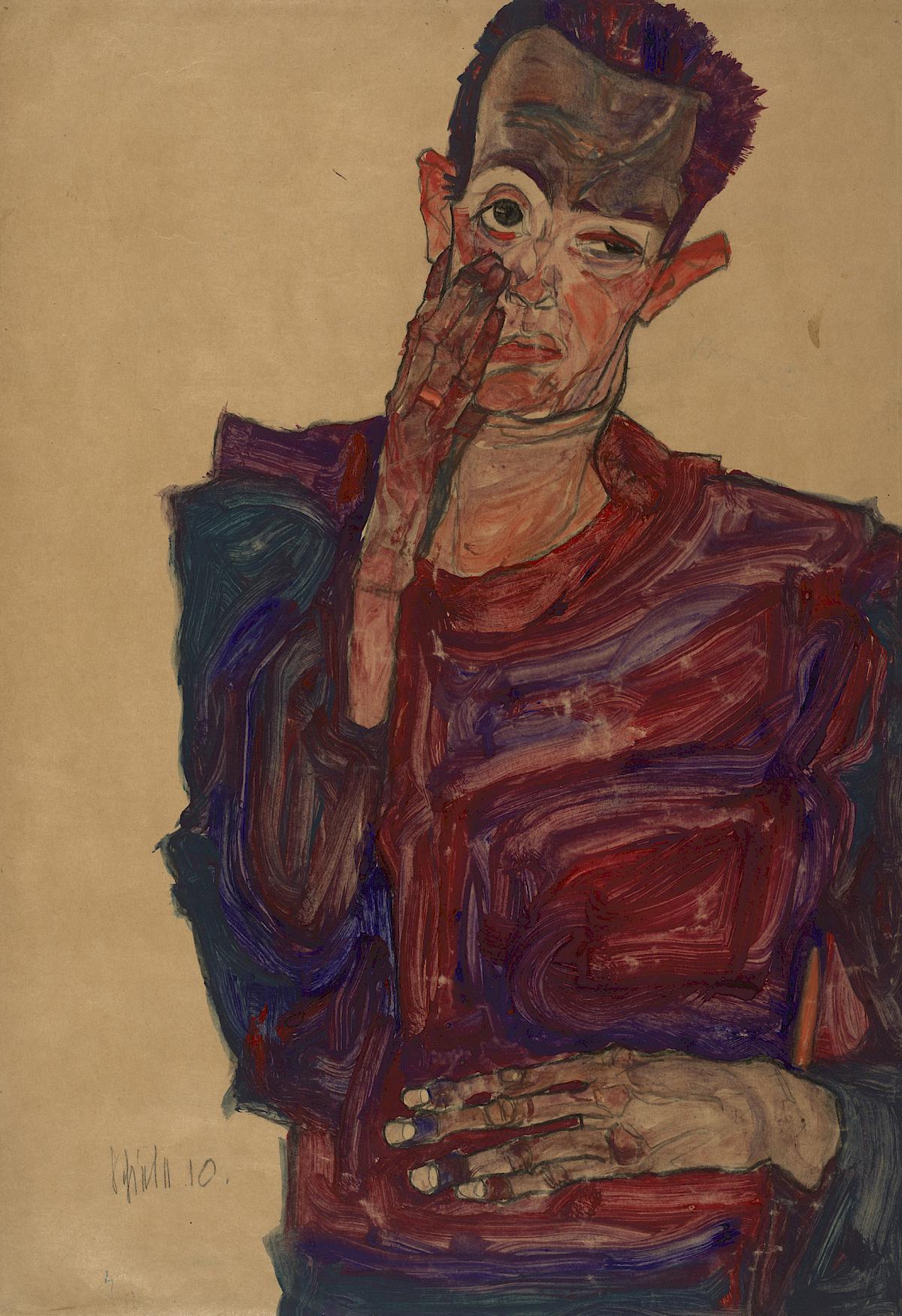

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait pulling down an eyelid (1910). Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: AB

If it’s any consolation, Schiele claimed:

A single living work of art will suffice to make an artist immortal

Any of his extraordinary drawings ratifies it, plus the whole his work, extremely disturbing. It leaves no one indifferent. Egon Schiele died in 1918 due to an epidemic, the Spanish flu, that killed as much as the World War I, after a supposedly excessive life. However he died in a good time of his life, on the verge of being father and as a young recognized painter, the most promising member of the Viennese Secession after the death of Gustav Klimt a few months before him. Egon Schiele lived in the turn-of- century, in an artistic sense between the so-called decadence of fin de siècle in Vienna and the European avant-gardes. We study his painting within the framework of the Viennese Secession, an art movement that was formed in 1897 by a group of Austrian painters, graphic designers, sculptors and architects, including Josef Hoffman, Josef Maria Olbrich, Koloman Moser, Otto Wagner, and Gustav Klimt, artists which broke up with traditional artistic styles.

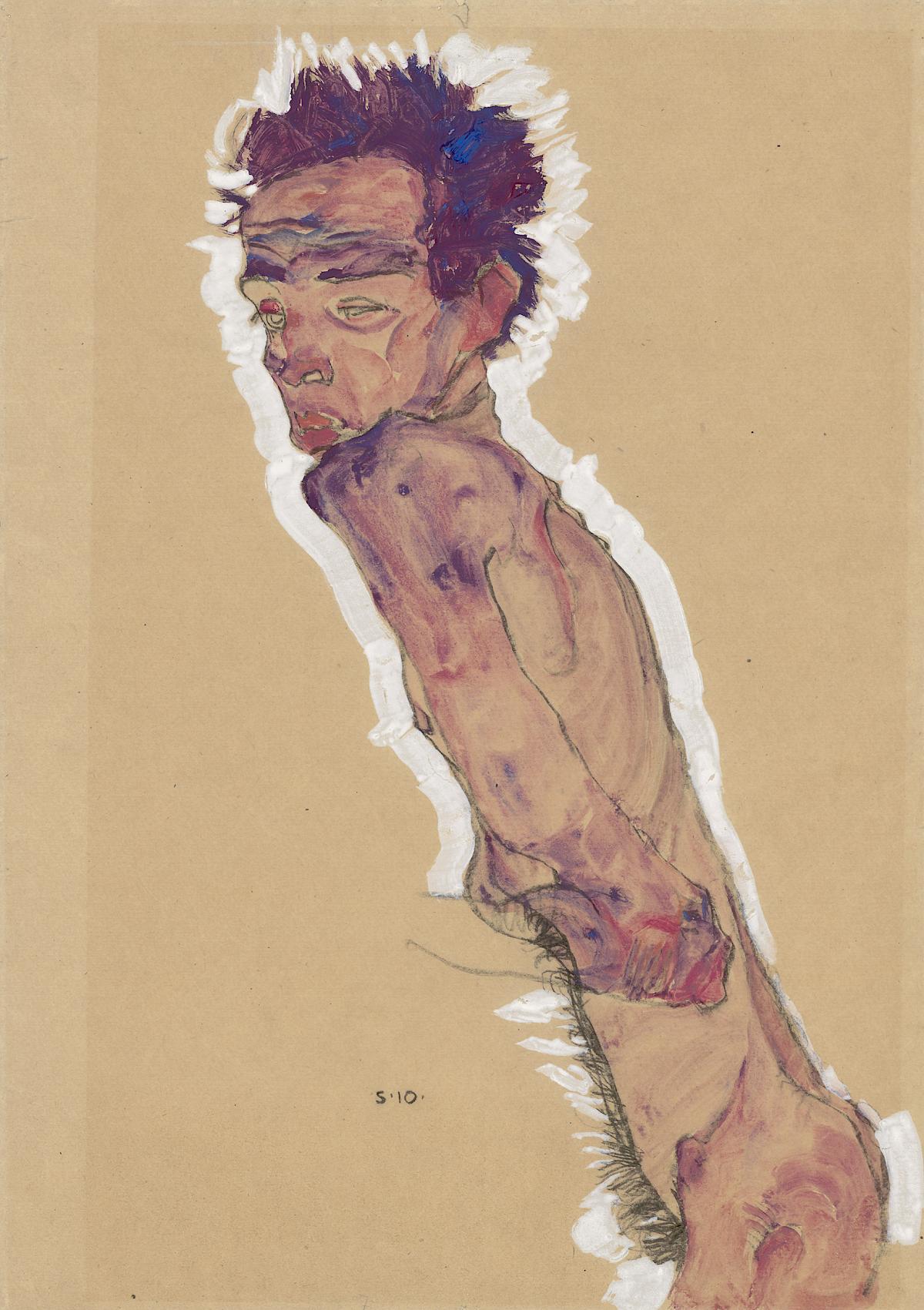

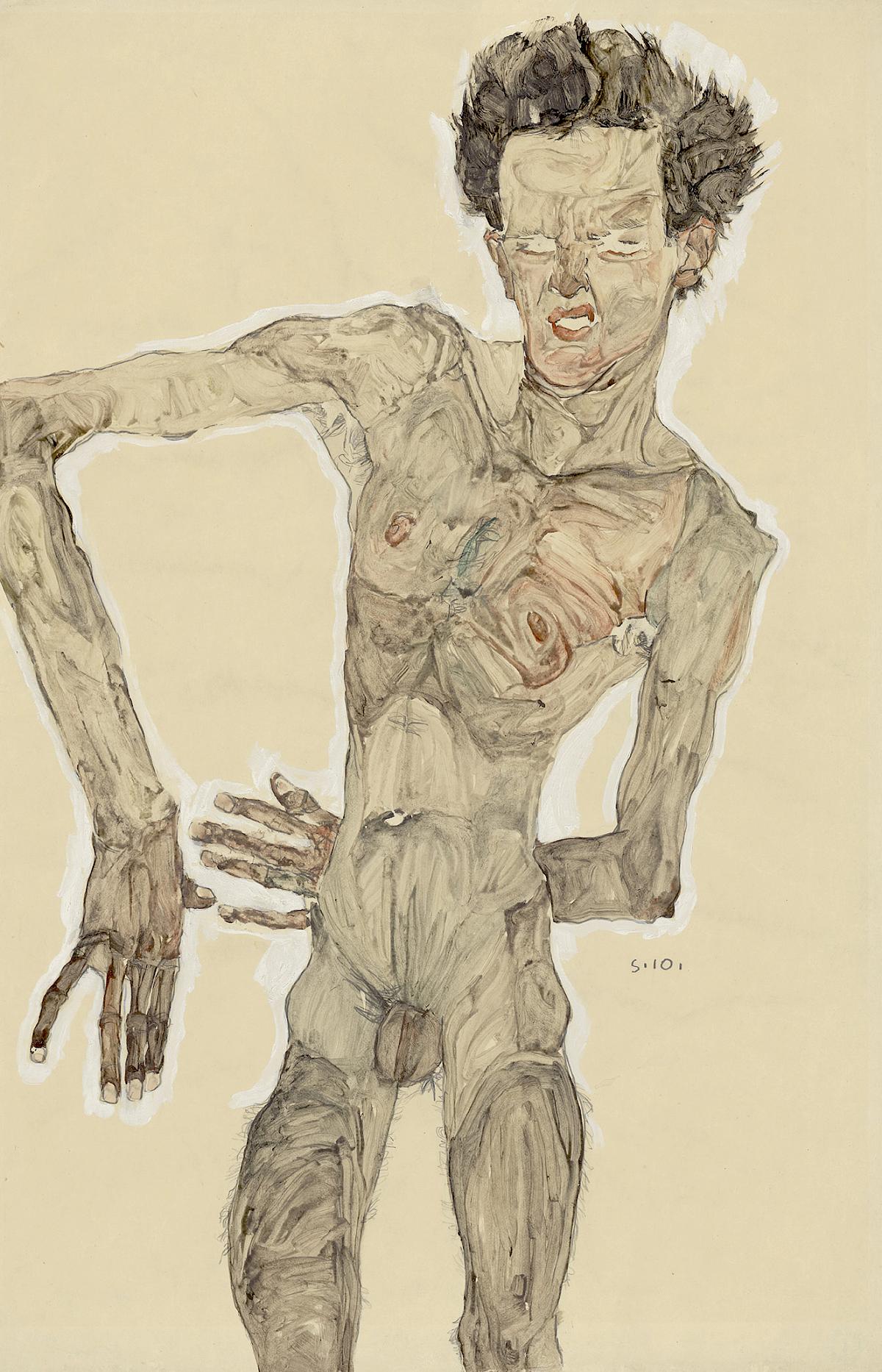

Egon Schiele. Nude Self Portrait (1910). The Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: AM

Schiele, however, has a very personal style, a way of drawing and painting different from other Secession artists, his works reflect his gloomy moods, his complex and maybe neurotic personality and his erotic/love relationships. When we see his self-portraits, it is inevitable to think that they were painted by a person with mental disorders, however, in the turn-of- century, there was a lot of interest in the link between art and mental illness. Artists who drew faces and gestures of lunatics and psychiatrists who studied the drawings and paintings of the mentally ill in order to understand their behavior. Likewise painters and sculptors of the Expressionism avant-garde tried to fix rare faces, the grotesque in human beings, that sometimes comes from mental illness. It was not new. In the 18th century German-Austrian sculptor Franz Xavier Messerschmidt made a series of “character bust”, a collection with faces contorted in extreme facial expressions, close to the pathological. Himself was considered a lunatic. Schiele may have seen these bust in Vienna and been inspired by them. Spanish painter Goya captured characters that we would now seen with mental disorders in much of his paintings and engravings; 19th century painters used the faces of criminals and mentally ill as an experiment to pictorially define moods. Leonardo da Vinci did it too. And Surrealist artists are not far from this artistic procedure.

In the painting The Hermits, the two life-size figures that impress you a lot when you are in front of them, participate in this art where one can dive into several pathologies. The figure on the left is Schiele himself, whereas the second figure who seems to be dying there is no agreement between the specialists: it could be his friend and mentor Gustav Klimt, his father or Saint Francis of Assisi. He wrote in a letter to his collector and patron Carl Reininghaus that this painting shows a mourning world in which the two bodies find themselves:

The bodies of those who are tired of life, suicidal and yet, bodies full of feeling. Think of the two figures as a cloud of dust similar to the earth that wants to pile up and must collapse due to lack of energy.

Egon Schiele. Two Women (1915). Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: AM

German critic Max Nordau coined the term Entartung (degeneration), a term later used to baleful effect by the Nazis and thus made it possible to condemn all works of art outside to the traditional norms calling them “sick”, degenerate. It was an accusation Schiele had to be defended against too. He painted degenerated people? When he painted himself, he painted a degenerate man? We talk about mental illness or extreme sorrow in his case? Or his figures, men or women, in fact, are they helpless puppets? Sometimes it seems they are.

The dilemma in Egon Schiele is about figuring out if his disturbing self-portraits may express the very essence of an entire era o are simply a trait of the artist personality that we might consider narcissistic. The huge number of about a hundred self-portraits shows that certainly he did devote a manic scrutiny to his own person, he liked very much to record his own appearance and poses. Anyway, he is not the first artist of portraying himself. Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, Ferdinand Hodler and Van Gogh used the mirror in order to record their own appearance many times and so establish and autobiographical account.

We can say that Schiele’s self-portraits are an autobiographical reportage and the ones of a narcissist, but according to Art Historian of the Stuttgart University, Reinhard Steiner, are beyond that: “The poses he strikes in them are extraordinary, his gestures highly effective, and the portraits deny and dismantle the oneness of the self. A tension is created between the actual self and the self seen in alienated form in the picture and this tension attests not the confirmed certainty of individual identity bur rather its end. Some of the self-portraits may recall Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), in which painted self grows older while the beauty of the real self remains unchanged. The image in his mirror served Schiele not as a way of fixing his identity but to promote the quest for the other self he portrayed in his pictures.”

Biography

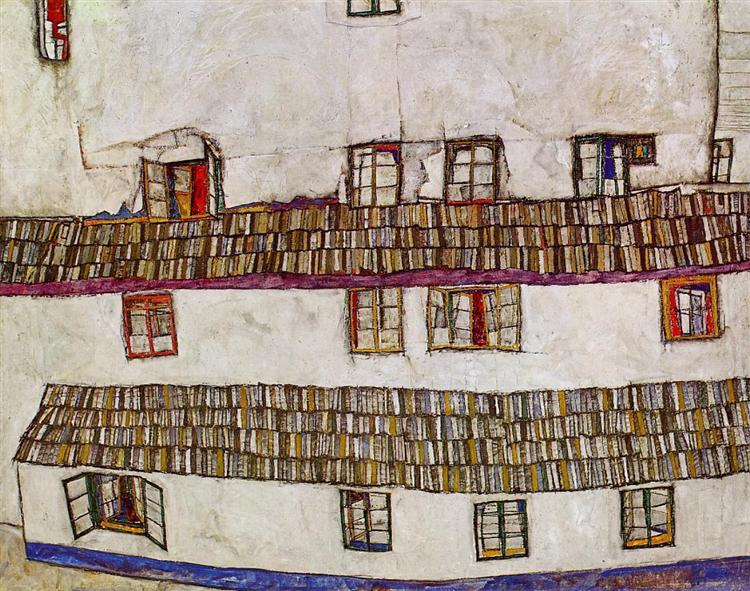

Egon Schiele was born on June, 2, 1890 at Tulln, a small town near Vienna, the third of four children of Adolf Eugen Schiele, an stationmaster on the Austrian-Hungarian Imperial Railways, who came from northern Germany, and his wife Marie, who came from Krumau, Bohemia. And it was from his father that Egon inherited his lifelong penchant for railways. His grandfather had been a railway engineer too. His first childhood drawings were of trains and his townscapes with their uninterrupted string of horizontal visual units. We often have the feeling that they record the view from a train window as well as the row houses look like train cars. He traveled by train frequently and as an adult he continued to play with toy trains.

Egon Schiele. Facade with windows (1914). Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikiart

In 1902, his father was pensioned off for mental illness and dies two years later when Egon was 14. Very fond and close to his father, his dead was a terrible shock for him. He began drawing and painting non-stop, including his first self-portraits. He said that his father spoke to him in dreams. Steiner points out that the striking earliest self-portraits (1905 to 1907) is the Schiele’s attempt to use exhibitionist versions of himself to compensate for the absence of his dearly-love father’s praise: “After his father’s death, self-portraiture was presumably an ideal way for Schiele to make up for the loss of someone who was so important to him and whose approval he now felt the lack of.” A perfect albeit egotist method of replacing the lost, idealized father’s image.

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Striped Shirt (1910). Leopold Museum, Vienna. Foto: artsy

Quite apart from the financial difficulties that resulted of his loss, he felt the father’s lack even more because he never had a warm-hearted relations with his mother that worsened when he became the only “man” in the household, but under the supervision of a guardian, his uncle and godfather, Leopold Czihaczek. Egon grew up alongside two sisters: Melanie and Gertrude (Gerti). Gerti was a frequent model for him and later she married his close friend, the painter Anton Peschka. Death was no stranger to the Schiele family, there were two children still-born and another one lived to be only ten. Schiele’s stated that death shaped him as an artist, became a major theme.

Egon Schiele. Gerti Schiele (1909). MoMa, New York. Foto: Wikicommons

Schiele was a weakly and a reserved child who preferred his own company to that of others. He was not a brilliant student at the school and even had to repeat one year, he said that his uncouth teachers were always his enemies. The only subject for which he could muster any enthusiasm was drawing. His Klosterneuburg school teacher, Ludwig Karl Strauch, the painter Max Kharer, and Wolfgang Pauker, master of the Augustinian choir, all supported his early efforts. At the early age of 16 he was accepted into the Vienna Academy, encouraged by the aforementioned teachers and against the whish of his guardian Leopold Czihaczek. He joins Christian Griepenker’s class, but his time at the Academy was unremarkable even if he had a natural gift and the best skill as a draftsman. The Academy required time-honoured discipline of him: the study of ancient statuary, of the living models and draperies and compositional exercises. Schiele had aversion to the academic exercises, although they helped perfect the draughtsman’s gift he already possessed.

The relationship with his mother was a very complicated one. His mother had actively supported his wish to attend the Vienna Academy, but she had to guarantee the expenses of his student son and those of the family, but there was no excess money. It seems that the problem was him. Steiner describes it harshly: “He could hardly be called a grateful son. Obsessed with the thought of his artistic vocation he took it for granted that his mother would make sacrifices for him, especially when his father’s death left him head of the family. He was cruel to his mother, he felt she was an stranger.” Due to the precarious financial situation the mother expected greater support from her son and from her point of view she was not enthusiastic at Schiele’s prospect as an artist especially since those prospects involved a lifestyle which must have seemed irresponsible to her.

Egon Schiele.Blind Mother (1914). Leopold Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikicommons

“Schiele demanded an almost unconditional willingness to make sacrifices and subordination to his own will; and this made conflict inevitable”, points out Steiner. Whatever our moral view of this conflict Schiele confronted it in his paintings. He worked on a number of variations of the theme of mother and child which suggest that the matter retained a bitter taste for him, reflects an unhappy motherhood, almost unbearable. The mere titles are alarming: dead mother, blind mother, etc. There is a written testimony of this relationship. His mother curses him in a letter, and the answer to the mother’s curse was:

Dear mother! (…) You do me an injustice…I want to enjoy the pleasure I take in the world that is why I am creative, and woe to the one robs me of it. Got it from nowhere, and nobody helped me, I have only myself to thank for my existence.

According to Steiner, this answer can only be read as a “classic example of wounded narcissism and he seems only to be pretending to understand and attempt a compromise.”

Egon Schiele. Dead Mother (1910). Leopold Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikicommons

Dead Mother is one of the most frightening works of the then twenty-year-old artist. He wrote to his friend and Art Historian Arthur Roessler, who was the first owner of the painting:

It only now occurred to me that Dead Mother is one of my best.

Roessler received the painting as a gift from the artist and hung it in his study. Every part of the depiction exudes the tragedy inherent to the subject, a child admittedly still alive but trapped in the lifeless mother, shows up despair, revenge or misunderstandings and… misogyny. The Leopold Museum describe the painting as follows: “The mother’s features are haggard, her eyes broken and her head turned unnaturally to the side as she tenderly embraces her child. The language of color speaks volumes. The mother’s skin is rendered in cool and earthy colors – life is over, her body is a dead shell for the child that grew inside of her. The child seems hopelessly lost; even if its orange- and crimson-colored skin signifies vitality and life, the mother’s death will nevertheless seal its destiny, in addition to her own.” In the context of the time, this painting and those in the series on the mother, must be understood in the tradition of Symbolist painting that closely linked motherhood and the fear of death. In fact, at that time, many women died in childbirth and infant mortality was very high. And as I mentioned, death visited the Schiele family too many times.

Egon Schiele. Standing Girl in Checked Cloth (1910). The Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Foto: MIA

When Egon Schile began his short career, Vienna lived an artistic effervescence with the Secession, with Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), as one of the most notable representatives. So, he was early strongly influenced by the style of Klimt. He was impressed by his flat-dimensioned linear style and by the Secession artists. Schiele declared his affinity to the movement. While he was at the Academy as a teen, Klimt became his shining example, one he revered until his death. This election in itself was an act of rebellion against the Academy instruction very traditional. Schiele adopted Klimt’s principles, above all the emphasis on the flat surface, a fine drawing and the decorative values although already distancing himself from these. For example, we can see that in the aforementioned portrait of his sister Gerti and in the works Standing Girl in Checked Cloth and in Spirit waters, however his own personality and style are inside. At only 18 years old, he exhibited his work for the first time in Klosterneuburg. A year later he left the Academy, where he did not do especially well and because he couldn’t bear its conservative teaching methods. Then he founded the short-lived Neukunts-gruppe (New Art Group) with his friends and former Griepenkerl students, Anton Faistauer, Karl Massmann, Anton Peschka, Franz Wiegle and others. But he left the Group soon after a first unsuccessful exhibition at Vienna’s Pisko Gallery and he decided “to go alone”. He wanted to be exhibited “solo”.

Egon Schiele. Nude Woman Lying on her Stomach (1917). The Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikiart

From 1909 on Schiele put the elegant linear clarity of a Klimt increasingly behind him and evolved a style in drawing which even Klimt acknowledged as the style of a master. The first meeting of the two artists probably took place in 1910. Schiele ask Klimt if they might exchange work, naively saying that he would gladly give several of his own drawings for one of Klimt’s. Klimt replied: -Why do you want exchange with me? You draw better than I do anyway… He gladly agree to the exchange and also bought a few more drawings. In 1910 after his first solo show he wrote in a letter to Dr. Josef Czermak:

I went by way of Klimt till March. Today, I believe, I am his very opposite…

And he evolved his own style. His ambition was so great, he was so sure of himself – or wanted to prove it – that he wrote:

My pictures must be placed in buildings like temples.

Egon Schiele. Fighter (1913). Private collection. Foto: Wikimedia

And he paints and draws himself over and over again. Contorted, with a physical slimness, like a skeleton, grim and bizarre facial expressions, fierce at times, sometimes like a paranoid man, he is supposed to look at himself in the mirror, but the represented character in his paintings is really him? Seeing this self-portraits as a whole, a multiple self appears to us where, although it seems a paradox, it forms an unitary visual concept. As Steiner explains, Schiele was already seeing himself as a kind of priest of art, more the visionary than the academician, seeing and revealing things that remain concealed from normal people. So, although they are and he is well recognized, it is not easy to see his paintings only as self-portraits since in his style we never speak in terms of mimetic realism. Sometimes they are quite an enigma. It should be said that he is not at all complacent with himself, he never wants to looks handsome, kind, on the contrary his gaze can be very malevolent, perversity emanates from his skin, he does not try to please the viewer in any way. Maybe is different for him. Lets him talk:

I always believe the greatest painters painted the human figure. I paint the light that emanates from bodies.

Krumau

Egon Schiele.View of Krumau (1916). Wolfgang-Gurlitt Museum, Linz. Foto: KRI

In 1910 he moved to Krumau, south Bohemia, his mother hometown. He wrote to Anton Peschka that he felt wretched in Vienna:

Everyone conspires against me, former colleagues regard me with malevolent eyes. In Vienna there are shadows.

He rented an studio along with Erwin Osen, an artist member of the New Art Group like him, an eccentric stage set painter which has been commissioned to do drawings of mental patients at the Steinhof asylum for a lecture on pathological expressions in portraits. In Krumau Schiele turned his eyes to nature. He wanted to feel nature in Bohemian forest. He wrote:

… I want to gaze with astonishment at mouldy garden fences. I want to experience them all, to hear young birch plantations and trembling leaves, to see light and sun, enjoy the green-blue valleys in the evening, sense goldfish glinting, see white clouds building up in the sky, to speak to flowers, to old venerable churches, to know what little cathedrals say, to run without stopping along curving meadowy slopes across vast plains, kiss the earth and smell soft ad warm marshland flowers. And then I shall shape things so beautifully: fields of color…

He wrote about nature but in fact in Krumau he produced numerous expressive nudes. Joined him Valery (Wally) Neuzil. Very little is known about her, actually. She was the illegitimate daughter of a day laborer and a teacher, born in a town in southern Bohemia. He met her in 1911 when he was 21 and she was 17. It seems that she had been a model for Klimt and might be her lover. Probably Klimt introduced her to Egon and “gave it to her.” With Wally he would spend the next four years. She was his favorite model, she appears in most of his erotic drawings and in several of his most important paintings.

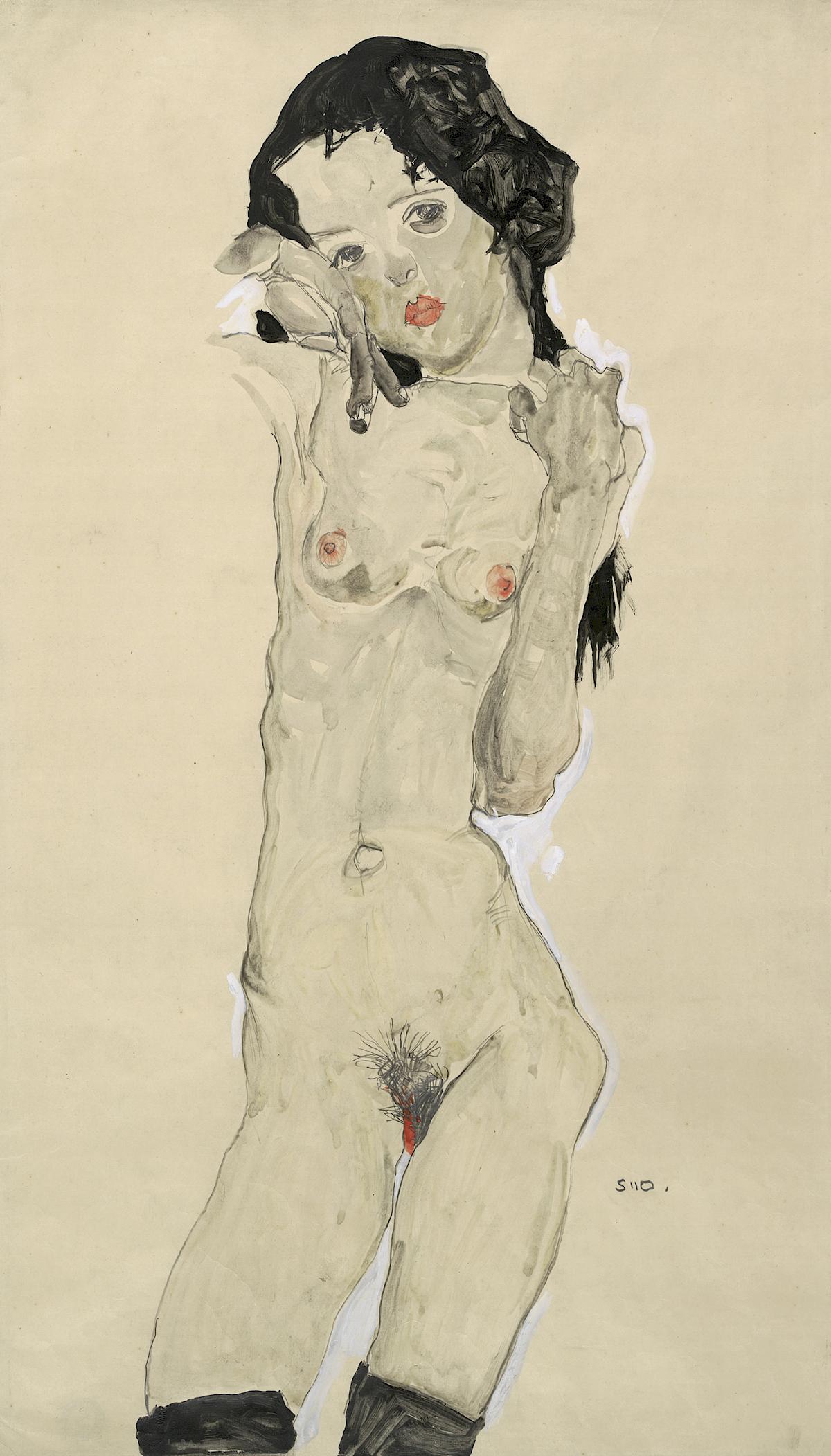

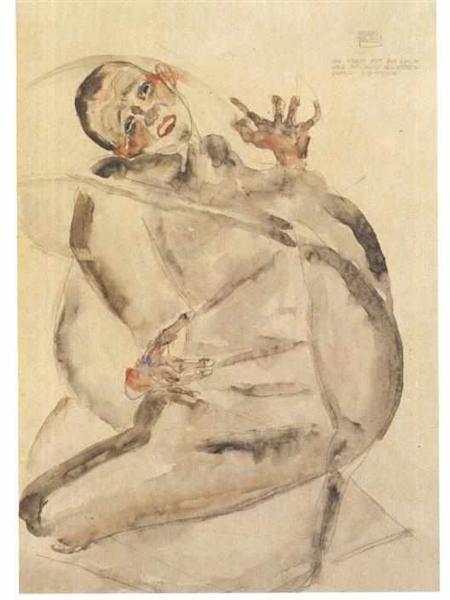

Naked body

In Schiele the naked body was becoming a central subject in the portrayal of self from 1910 onward. I mentioned the relation of the subject with the death of his father symbolically. For Schiele, the nude is the most radical form of self-expression because he believes that with the body exposed as it is, without the veils of clothing, the self is fully captured; hence he almost always shows it in an empty space, without accessories. Schiele neutralizes the background by using a monochrome one-dimensionality that makes the bodies look insecure and gives their movements a spasmodic or nervous quality. The irregular, angular outlines of the figures, contrasting so sharply with the neutral background, contribute to the defamiliarization of natural mirror image and make possible a greater physical expressiveness, the brusquely juxtaposed brush-strokes instill an energy sometimes overflowing, sometimes disturbingly contained.

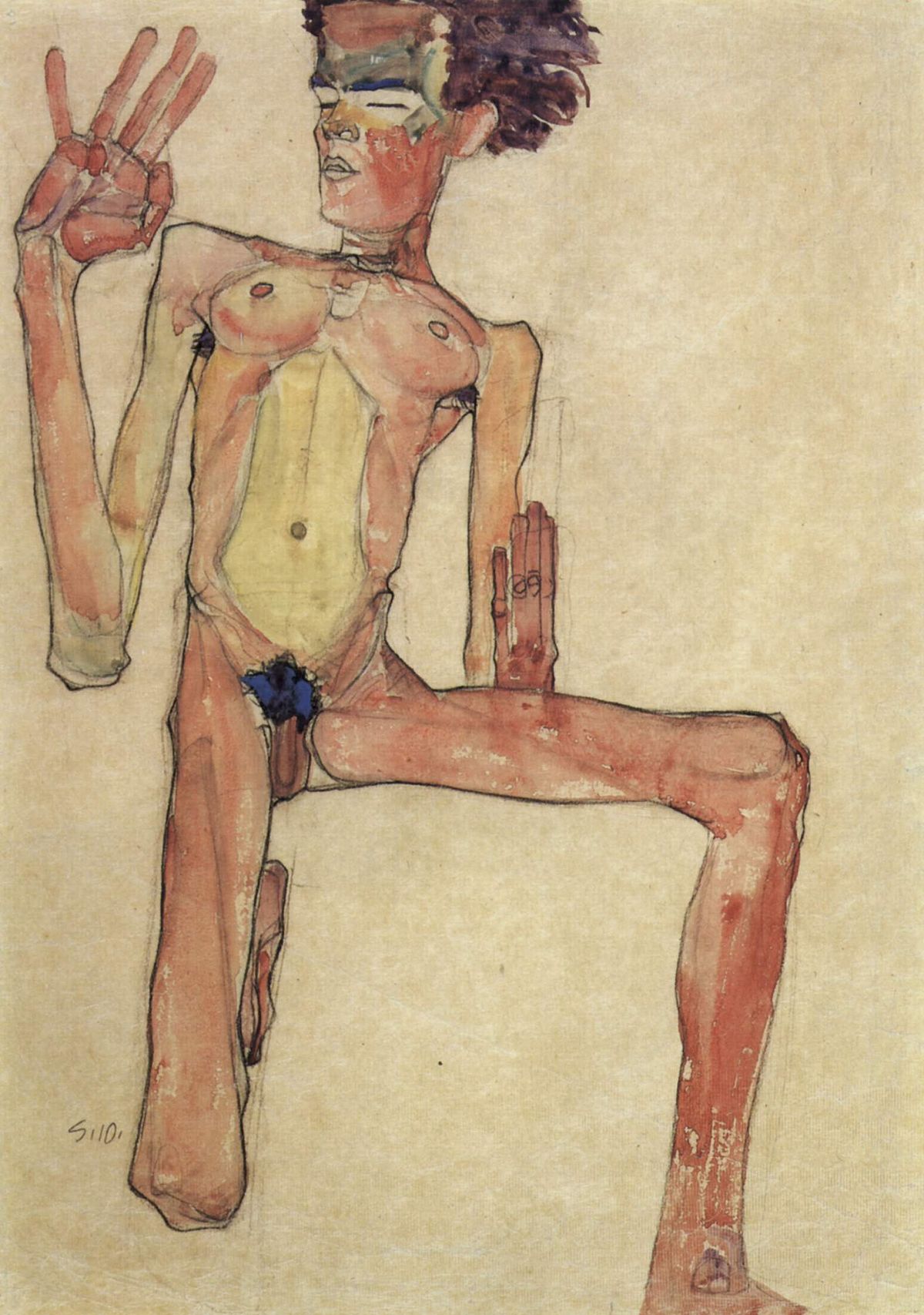

Egon Schiele. Seated Nude Male (1910). Private Colecction. Foto: Wikicommons

Particularly when he mutilates the body to a mere torso that has little to do with a normal appearance as if they were broken dolls. He wrote in a letter to Dr. Oskar Reichel, one of his collectors, in 1911:

When I see myself entire, I shall have to see myself and know what I want, not only what is happening within me but also to what extent I have the ability to look, what means are mine, what enigmatic substances I am made of and of how much of that greater part I perceive and have hitherto perceived in myself. I see myself evaporating and exhaling more and more, the oscillations of my astral light are growing faster, director, simpler, and like a great insight into the world. Thus I am constantly accomplishing more, producing further and infinitely more shining things from within myself, insofar as love, which is everything, endows me in this way and leads me to what I am instinctively attracted by, what I want to drag into myself, in order to make something new anew that I have seen in spite of myself.

It’s obvious that his nude self-portrait involves narcissism and exhibitionist. But beyond that, the artist himself, naked, is after all exhibiting as a sexual creature. It may well be true that Schiele was out to exorcise sexual devils, and was living out in his imagination “impulses that could not be always satisfied in reality. In other words to portray one’s drives and passions is to cope with them”, points out Steiner. But Schiele’s friends did not describe him as an unbridled erotomaniac. Despite the frequently unsightly, tortured look of his nakedness, Steiner believes that it would be a mistake to overdo the erotic component. What seems of greater moment (and is expressed in his letters and poems) is the fact that Schiele placed great emphasis on understanding and exploring the self: “This exploration was not a mystical, anti-physical thing for him; rather, it was a way of locating energies through the medium of the body as spiritual substance.”

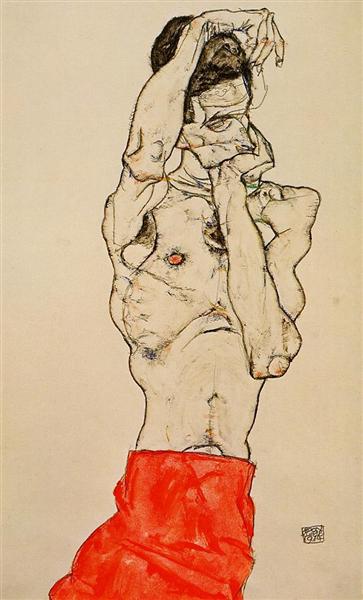

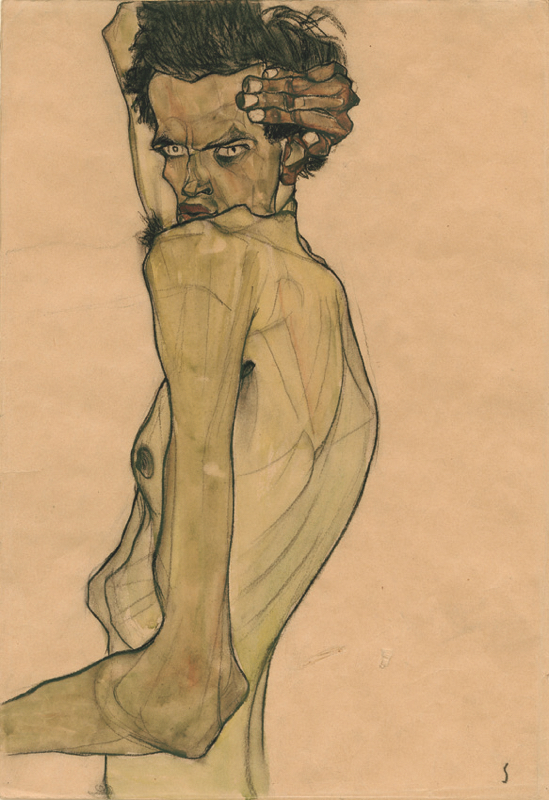

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted above Head (1910). Private collection. Foto: Neue Gallery

Schiele belonged to the Viennese Secession, but his nudes are very expressionists. Since 1909 he began to develop his own distinct Expressionist tendency and would abandon the decorative style associated with the Secession and the Jugendstil. Paul Hatvani, in his “Essay on Expressionism” (1917) define it: “The Expressionist work of art is not only connected but indeed identical with the artist’s awareness. The artist creates his world in his own image.” Hatvani’s observation points the way to a re-interpretation of the myth of Narcissus, one that applies not only to the self-portraits but to Schiele’s entire work: “The modern Narcissus does not create an artistic image that reproduces the real shape of things, rather, he reverses the perspective scrutiny of the world and in this reversal the ego or subject itself becomes the horizon, the ego inundates the world.”

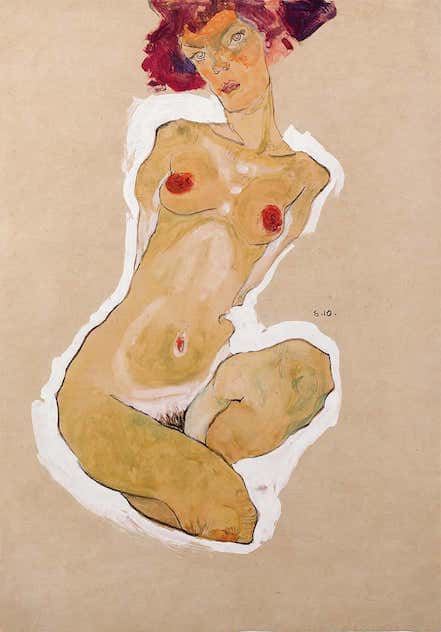

Schiele’s erotic drawings are unsettling because the artist subverted established conventions. Women, instead of being passive receptacles for male desire, they offer themselves, their bodies are bluntly arousing. By omitting any surrounding detail from his drawings and frequently giving recumbent figures a vertical reading, he created a profound sense of spatial dislocation. Even by today’s standards, these drawings grant women an uncommon degree of sexual agency, even with clothes on. Above all controversy or exploration about his personality, Egon Schiele was a genius draftsman. Schiele’s line seem both frail and clenched, very personal. It is often fragmentary, hardly ever straight or rounded. It breaks off, and becomes more forceful or less so depending on the emphasis that is to be placed on particular detail. And yet the line is always so assured and controlled. The line encompasses and contains everything.

Egon Schiele. Heinrich and Otto Benesch (1913). Neue Gallery, Linz. Foto: Wikicommons

Austrian Art Historian Heinrich Benesch (portrait above) saw him drawing and he described him as follows: “The beauty of form and color that Schiele gave us did not exist before. His artistry as draughtsman was phenomenal. The assurance of his hand was almost infallible. When he drew, he usually sat on a low stool, the drawing-board and sheet on his knees, his right hand (with which he did the drawing) resting on the board. But I also saw him drawing differently, standing in front of the model, his right foot on a low stool. Then he rested the board on his right knee and held it at the top with his left hand, and his drawing hand unsupported, placed his pencil on the sheet and drew his lines from the shoulder, as it were. And everything was exactly right. If he happened to get something wrong, which was very rare, he threw the sheet away; he never used an eraser. Schiele only drew from nature. Most of his drawings were done in outline and only became more three-dimensional when they were coloured. The colouring was always done without the model, from memory.”

Neulengbach

In 1911 he was obliged to leave Krumau. The townspeople objected to Schiele’s lifestyle and the fact that children visited the studio and posed for the artist in the nude; also because of the presence of Wally who posed naked for him. In turn-of-century, sometimes, artist’s models occupied a position close to prostitutes and the artist might fall in love with them, making then, his position more respectable. Not for poor Wally.

Egon Schiele. Two Young Girls (1911). The Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: AM

Egon and Wally found a new place to live at Neulengbach, in the west of Vienna. A year later he was arrested and subsequently transferred to St. Pölten prison, his erotic drawings were confiscated and he was accused of “seducing” and “violating” an under-age girl. About the accusation of a minor rape it seems that never took place. Jane Kallir, the author of the Egon Schiele catalogue raisonné, states: “The “incident” was precipitated by a teenage runaway, who asked the couple to take her to her grandmother in Vienna. Once in the city, the girl got cold feet, and the three returned to Neulengbach a day later. By then, however, the teenager’s father had filed charges of kidnapping and statutory rape, which led the police to conduct a thorough investigation of the artist.” In the course of that investigation, they search the house and found erotic works of art in his studio and another charge was levelled againts him: the crime of “Public immorality” because the minors who hung out at his studio after school would have seen them.

His friend Heinrich Benesch defended him saying that Schiele, when he had finished drawing child models, would often let whole hordes of boys and girls, the model’s schoolfriends, come into the room and romp about. Schiele had pinned up on the wall only one single sheet in color of a very young girl clothed from the waist up. Children who were no longer wholly innocent would whisper about it, and talked, and that was how the charges came about. The drawing was subsequently destroyed at the order of the court. At the trial in St Pölten the charge of sexually abusing children was dropped and he only was given a three-day of prison sentence for displaying immoral drawings where they were visible to children, a sentence which took into account the fact that he had already spent three weeks in custody by the time of the trial. It is said that in his defense he claimed:

I’m an artist. My responsibility is to defend the freedom of art.

In 2018, in the lot of complaints of sexual harassment linked to the #MeToo movement, the New York Times included Ego Schile in its list of abusive artists. It must be said that Wally supported him throughout the Neulengbach affair, she saw him innocent, she was the one who brought him paint supplies to jail and found him a lawyer.

Egon Schiele. Self Portrait as a prisoner (1912). The Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikiart

In prison he did thirteen watercolors recording his experience of detention. He appears as devastated victim, with fearful and tormented expressions because of the isolation and imprisonment. He wrote on the drawings sentences like that:

– I feel purified rather than punish.

-To hinder an artist is a crime. To do so is to murder burgeoning life.

From a compositional point of view, Reinhard considers that the Neulengbach drawings can be seen as extreme examples of experiment, with his own person as preferred subject. The poses are artificial, and in most of them he paints himself with heavily exaggerated gestures and facial expressions.

Egon Schiele. The Embrace (1917). The Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Foto: BM

In fact, he painted erotic subjects all his life, men and women alone or together. At that time, society whose official morality was prudish and bigoted, took offence at his nudes. Certainly, they are so crude, so “real”, some evidently pornographic, he deprive the viewer the opportunity to keep a distance. His aggressive nudes, male or female, were painted without the fig leaf of the myth that covered the privates, it was an obsessive scrutiny that does not avoid the nature and the sexual gaze. And even today it must be recognized that they can offend many puritanical people who see them as an immorality and obscenity matter. According to Steiner, ”his nudes morally speaking in dubious positions led him in prison.” This event established a romanticized image of a misunderstood artist, a product of the morality of the time. Today, as a well-known artist, what happened in Neuenbach would be a topic exploited by the press ad nauseam and his relationship with the minors he painted would be probably investigated and condemned.

Egon Schiele. Seated Woman with Left Leg Drawn Up (1917). Národní Gallery, Prague

Schiele’s relationships with women are difficult for us to judge, not only because no living witnesses survive and they have not left written testimonies but also because present-day standards are so very different from those that prevailed in early 20th-century Austria. Schiele was, of course, hardly a feminist neither was Klimt, nor most of the artists of this time, this concept did not even exist as we understand it now. Jane Kallir points out: “Current views on gender have been decades in the making, and he was very much a product of his time and place. However, unlike many men then and since, Schiele embraced the mix of fear and attraction that often colors masculine responses to the female “other”. As a result, he created images of women who, mirroring his own ambivalence, boldly command their sexuality. Is that sexuality truly a kind of superpower, or does feminine allure inevitably entail capitulation to the patriarchy? The enduring relevance of great art lies in such questions, in ambiguous readings rather than simplistic formulations. To brand Schiele a sex offender is not only wrong; it ignores essential historical context and forecloses necessary dialogue.”

Another of his sentences:

Erotic works of art are sacred too

But the question is if he was only a voyeur like Klimt. Probably not, he was much more than that. Benesch says that what first strikes of his erotic works (as wells as his nudes) is that he abandons the normal use of perspective, which would provide a rationale for the positions his figures appears in. Anti-academic through and through, he devises angles and points of view from which the figures appear twisted, contorted or deformed, rarely viewing them frontally or fully establishing unfamiliar and alienating poses, bizarre movements. Compared to his beloved Klimt, Klimt’s female nudes are like “dreams of desire”, but they are protected. In Schiele the forced poses strips the model radically bare and leave her or him exposed and undefended. These bodies are hardly ever relaxed. Generally they are contorted in a manner almost acrobatic, they are exhibited, put on a show, offered up: “Schiele metaphorically ties his model down on an operating table in his optical lab, and examines the specimen with a clinical gaze, dissecting the creature at his mercy with his pencil. Thus is that most of his nudes do not seem intimate or absorbed in their own words, but instead isolated and tensed, frequently they are looking straight us”, writes Steiner. They are looking at us cheekily. He provoked it. He took up a vantage point directly above them when occasionally drew his models from a position on a ladder. Anyway, after the jail experience, children almost disappeared from his thematic repertoire and the erotic element became less overt.

Schiele dramatized his prison experience, but he traveled to Carinthia and then Trieste not so much to escape an unpleasant memory as for the sheer pleasure of travel and to recover. The affair didn’t damage his career. In the same year, he exhibited in Budapest, Munich, Cologne and Vienna again, and collectors took an interest in his work, which made an improvement in his financial situation. He moved to a studio in Vienna and began a kind of frivolous life. He invested the proceeds of his sales in expensive clothes, he could satisfied his tastes for fashion, number of photographs taken in 1914 show Schiele in his penchant for vain posing, with hats and suits, all in a way his mother couldn’t understand because at that time his family was not well-do. He became a young dandy in contrast with an eccentric, scandalous and inquisitive work that was far from offering comfortable stylishness for the Viennese gentry and aristocracy, at least in such a graphic way, but they liked it and bought his work, perhaps precisely because it reflected their intimacy or their most unspeakable desires or their attraction to the dark part of the soul that many human beings share. In 1913 Shiele’s career success was consolidate: he became a member of the Federation of Austrian Artists (the president was Klimt) and exhibited in important shows among them the Vienna Secession’s International. His work were also exhibited in German cities: Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Stuttgart etc. In 1916 Die Aktion magazine devote to him an entire number.

Puppets

Schiele scholars and critics has long held that the artist’s work is based on a very private mythology drawn from the unconscious, a kind of maniac demoniac. I’m sure about that, but also there are more premises. Arthur Roessler, who encouraged and sponsored young talent and particularly Schiele, wrote that “his stylized, expressive figures, exotic figures comes from the puppets of the Javan shadow theatre. He used to play with this figures for hours, he has a skill in order to manipulate the slender sticks that moved the puppets from the very outset. And the figure he liked the most was the grotesque of a diabolical demon with a rakish profile. He was fascinated by this figure and the other shadow figures, left a deep impression.” Also, it should be noted that he liked dance, to contemplate the contortions of the dancers motivate him very much and especially he admired Ruth Saint Denis. She was an American dancer who was in Europe at that time. Her acrobatic movements, her mysterious eroticism, her angular gestures were similar to his own artistic definition of the human body.

Edith

Egon Schile. Edith Schiele (1915). Moderne Kunts, Hague

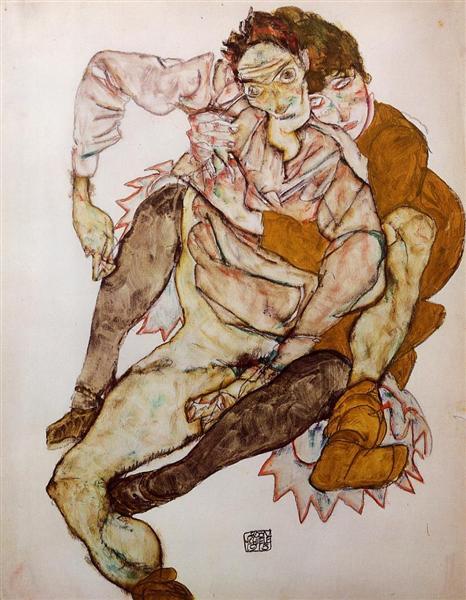

In 1914 he met the young sisters Edith and Adele Harms, pretty middle-class women, daughters of a railway employee, who lived across the street. He would strike odd poses at his window, or howl “like an Indian”. Drawing their attention, invited them on excursions and walks. The attraction for Edith was stronger but he was living with Wally. Edith Schiele was an attractive woman whose features were ideally suited to the artist’s style of portraiture. She was slim, with a classically beautiful face with pointed chin and feminine features. He made a portrait of her that has long attracted comment for the subject’s vacuous appearance (image above). She has little to do with the cheeky and defiant women she painted before, she is quite the opposite, in the painting she looks like a doll or a vapid bourgeois young lady. Decades later, Adele, Edith’s sister, expressed her indignation that Schiele made her look dumb. Perhaps she inspired him tenderness, she is the invitation to another kind of life, a potential of homely happiness. Anyway, letters dating from 1914/15 suggest that he was irresolute for a lengthy spell about both women. His doubts went on canvas and paper.

He made several works that showed two young women locked in an erotic embrace. His solution was to propose a kind of ménage a trois, spending holiday together. Initially Schiele thought that if he married Edith he could still see his muse and model Wally Neuzil after the marriage, but neither Wally nor Edith shared his view. Edith was jealous and finally demanded a definite decision. His utopian dream of an untroubled existence with the two women and avoid a single, exclusive commitment was gone. He settled on Edith and he had described the marriage as “advantageous” since Edith came from a respectable bourgeois. Edith was educated in a convent and soon he discovered that she didn’t particularly like posing for him.

Anyway, it seems that he felt guilty for Wally or he may missed her. She loved him, she had given him full support during the Neulengbach affair, it was not just a relationship artist/model. In Death and the Maiden he expresses the grief at the loss of Wally with a despairing embrace. The ground is a patchy rust-color with greenish zones, and across it lies a crumpled sheet the white of which is also suggestive of a shroud. Typically for his style, the two reclining figures seem somehow in suspension of the canvas. The man, clad in a dark robe, is recognizable as Schiele himself, while the woman resembles Wally. Her head lies on his breast and hugs him. He makes the gesture of comforting her tenderly, but her gaze includes the sadness and the horror for what will inevitably to come: he is going to leave her to marry another woman. After the separation, Wally volunteered for the Red Cross. She never saw Egon again. She died of scarlet fever in Dalmatia.

Egon Schiele. Embrace Egon and Edith Schiele (1915). The Albertina Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikiart

Prague

We are in the middle of World War I. A few days after Egon and Edith married, in 1917, they left for Prague. He had to do his military service. Edith accompanied him and initially put up at the Hotel Paris and made his life more endurable when he could get out of the military facilities. After a basic military training, he was fortunate that he was not sent to the front and returned to Vienna, but the following year he was posted to Mühling in Lower Austria as a clerk in a prison camp for Russian officers, some of them posed for a portrait.

He kept a detailed war diary. In one of the notes he wrote:

To me personally, where I live is a matter of indifference, that is, which nation I belong to, or rather, which nation I live in. At all events I tend far more to the other side, that is, our enemies- their countries are far more interesting than ours- there they have real freedom and more thinkers than we have. But what is one to say about the war now? Every hour that it continues is a great pity.

He was not an apolitical but was unenthusiastic about the war from the start. Nationhood ideas of force were alien to him. To him war merely represented the wretched deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. He hated uniforms, soldiers and officials, clerics and all forms of collectivism. It took him an infinite number of attempts and official applications till he was stationed near to Vienna where he had clerical duties which meant he could live in his own house and not in barracks.

Landscapes and Plants

Egon Schiele. Four Trees (1917). Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikicommons

All things are living dead.

This slogan governed his existential mood in the pre-war years and it was only from 1915 on that his figures are not so tormented. Steiner believes that was “as if the bloody reality of war has overtaken his worst visions, and the artist’s imaginative powers were now altogether preoccupied with the possibility of restoring wholeness to the world. His townscapes and landscapes are the best place to see this process at work.” Although they are still gloomy and melancholics, his palette got warmer like in Four Trees. Plants, landscapes and townscapes were his new subject. Maybe it was due that his wife Edit could not permanently satisfy or was tired of the obscene demands for posing for an artist who knew no taboos. He exchanged figures for plants without ever losing the human trace. He achieved a method in which plants, trees and flowers were increasingly subjected to an anthropomorphic treatment. He wrote to collector Franz Heuer in 1913:

I also do studies but I find, and know, that copying from nature is meaningless to me, because I paint better pictures from memory, as a vision of the landscape – now mainly observe the physical movement of mountains, water, trees and flowers. Everywhere one is reminded of similar movements made by human bodies, similar stirrings of pleasure and paint in plants. Painting is not enough for me. I am aware that one can use colors to establish qualities. When one see a tree autumnal in summer, it is an intense experience that involves one’s whole heart and being; and I should like to paint that melancholy.

Egon Schiele. Sunflower II (1909). Historiches Museum, Vienna. Foto: Google Art

This approach to nature as an anthropomorfic figure can already be seen in Sunflower II. Steiner describe it as follows: “In a style comparable to the figure paintings of that period, the tall, delicate flower no longer appears wrapped in a decorative cocoon or ornamental lines, rather, it seems isolated, exposed. The way the sunflower’s large leaves are dropping recalls human gestures. The vertical format, coloring and quasi-human gestural repertoire make of the sunflower an image of feelings elegiac. A leafless tree on an ice-grey ground, bizarre angled to suggest movement reminiscent of ecstatic movements in expressive dance forms, he thought the subject is simple to the point of poverty. Schiele manages to make it a metaphor of sadness and transience.”

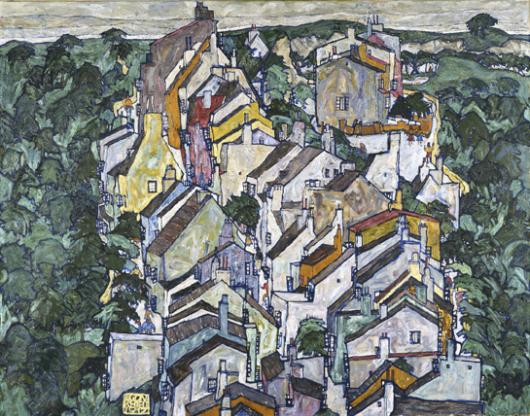

Townscapes

Egon Schiele. Deat Town VI (1912). Kuntshaus, Zurich

For Futurism and French Post-Impressionism, contemporary artistic movements to Schiele, the city, the traffic, the people and hustle were crucial, instead, he detested all that. He adored small towns and villages. He used to live in Vienna but he fled to small towns. As a man of an unpredictable mood, then, they sadden him:

I went to towns that seemed endless and dead, and felt sorry.

Anyway, Schiele was a man of his time and, as Steiner explains, the predilection for cities either dying or locked in a picturesque Sleeping Beauty slumber perfectly expressed the love of decay which was so characteristic of the decadent fin de siècle, in the Symbolist movement particularly. Melancholy and decay were popular. But unlike the symbolists, Schiele was not primarily interested in the age of towns and cities: “The sadness in his black and dead towns has nothing to do with observation and aestheticization of historical decline and decay. The dead or black town is for him the phenomenological epitome of a condition in the human spirit. (…) In dispensing with precise delineation of place, or verifiable topography, and in concentrating on the ‘facial expressions’ of the houses and towns, Schiele was ultimately creating a visionary parables of anti-urban experience.”

Egon Schiele. The old city III (1917). Neue Gallery, Newva York. Foto: NG

Austrian painter Albert Paris Gütersloh (1887-1973) realized that humans beings cannot live in these towns. He felt that the effect was a result of Schiele’s us of bird’s-eye-view perspective: “He calls a town which he looks down on from above and views foreshortened the dead town. Because every town looks dead seen like that. The hidden meaning of the bird’s-eye-view has unconsciously been revealed…” Gütersloh pointed out that the source of Schiele’s inspiration was the inner image or vision, these towns become projections of “the terrible guests who suddenly visit the artist’s midnight soul.” He learnt this method in Krumau and stated:

There you learn to look at the world from above; and unusualness of this way of seeing, this frontal view, acquires a painterly and graphic value…

When he painted human figures, he arranged them vertically and facing front in the composition, so it causes a destabilizing effect, the bodies totter or hover in suspension, revealing them, exposing them to indiscreet scrutiny. In the townscapes, by contrast, the bird’s-eye-view is not suspension but construction, as seen in the predominance of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines. It is the specific juxtapositions and relations of lines and spaces that produces the painterly and graphic values Schiele referred to. But at the same time these interactions produce a decorative, almost a craft texture in the paintings and drawings, like an illustrative dimension which, while in certainly explores atmospheric values with great sensitivity, remains largely free of conventional formality and symbolism.

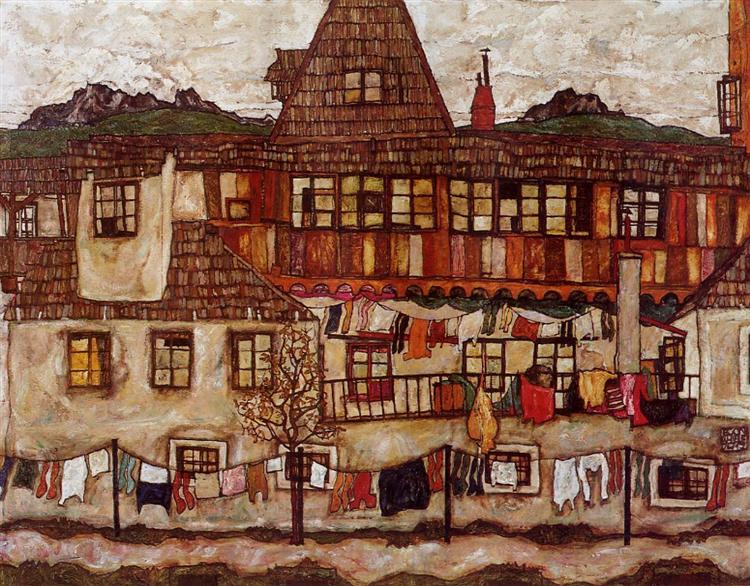

Egon Schiele. Suburban House with Washing (1917). Private collection. Foto: Wikiart

These townscapes seem tapestries because of its color and design. In his townscapes there is no industry, there are no smoking factories chimneys or other signs of technology. For him the city and modern life, the new civilization, has no place in his art. It was no mere nostalgia, but perfectly consistent continuation of the Ver Sacrum line of the Vienna Secession, that prompted him to believe in the remains of a noble civilization and these remains could only be preserved with the aid of the arts. Even he wanted to create an artist association called “Kuntshalle” that had no real chance in time of war.

Motherhood and dead

Egon Schiele. Poster for 49th Secession Exhibition (1918). Museum of Modern Art, New York. Foto: MoMA

Settled in Vienna in the spring 1917, he exhibited at a number of shows, and himself helped organize the “War Exhibition”. In February 1918 Gustav Klimt died. For the space of a whole generation he had been a kind of Viennese artists guide and to the end remained a venerated artist for Schiele. By this time Schiele’s name was becoming widely known and he saw himself as Klimt’s legitimate successor. At the 49th Vienna Secession Exhibition, Schiele was celebrated as the leader of the Viennese community, he designed the poster and his paintings and drawings made atremendous impression in the international press. It was his greatest triumph, his finest hour and he was well aware of his new status.

Egon Schiele. Mother and Two Children (1917). Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Foto: Wikidata

His marriage with Edith and the acceptance of living in a middle class normality wrought a change in Schiele’s approach to the subject of motherhood. It was no longer a matter of his own childhood, and the conflict with his mother, no longer a question of personal experience he felt to have been tragic. Mother and Two Children achieves a new tone which is free of conflict and death, serene. The longing for love and security which Schiele could only express symbolically through lack and reprobation in his earlier motherhood pictures has now been superseded by hope for a family of his own.

Egon Schiele. The Family (1918). Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Foto: Artsy

The family was his last important painting. Schiele shows himself, naked, seated on a sofa. In front of him squats a naked woman, Edith, with a child between her legs, all arranged in a pyramidal compositional structure. The color more dense than ever, providing an account of three dimensionality, creating a sense of physical volume and accentuating the presence of the figures, makes them more solid. They are no longer human figures like puppets suspended in an empty space. A vitalizing painting, compared to the previous ones. We see the man who has left behind malice and paranoia, hopeful and confident, about to start a family of his own, yet all the painting gives off an intrinsic melancholy, mainly Edith’s face, perhaps the painter had an intuitive knowledge that that happiness was not to be his. On October 28, 1918, his wife died of Spanish influenza. She was six month pregnant, three days after, on October 31 he died of Spanish influenza too.

Àngels Ferrer i Ballester

Main sources:

Reinhard Steiner. Egon Schiele 1890-1918. The Midnight Soul of the Artist. Benedikt Taschen: Köln, 1993

Leopold Museum, Vienna

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Belvedere Museum, Vienna

Neue Gallery, New York

Film: Exzesse. Directed by Herbert Vesely. With Mathieu Carrière, Jane Birkin and Christine Kaufmann